26 February 2021

The Hon Josh Frydenberg MP

To see the address on Josh Frydenberg’s website, please click here

Thank you Ian and the Council on the Aging (COTA) for hosting today’s national policy forum on retirement income.

I would like to acknowledge the constructive role that COTA has played – both prior to the Review being commissioned and since its completion. I especially want to recognise that COTA approaches these issues in a calm and considered manner – not seeking to sensationalise but rather seeking a balanced discussion based on the facts.

I also want to acknowledge that the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety is due to be released imminently and it too will make an important contribution to policy development in this area.

Australia’s population is ageing.

We are living and working longer.

And the nature of retirement is changing.

It was against this backdrop that I commissioned the first holistic review of the retirement income system since the early 90s.

The Review was conducted over a 10 month period by an independent panel: Mr Michael Callaghan, Ms Carolyn Kay, and Dr Deborah Ralston.

It received more than 430 submissions and produced a report in excess of 600 pages.

I want to thank the panel for their comprehensive assessment of our retirement income system. It is a body of work that will inform policy direction in this area for years to come.

I also note that the next Intergenerational Report will be released in the middle of this year. With the last IGR having been handed down in 2015, this year’s IGR will be especially important in highlighting the wider impacts of COVID-19. No doubt it will also contribute to our continued assessment of the effectiveness and sustainability of our retirement income system.

Today, however, I want to outline my perspective on the Review:

- first, the significance of the Review and why it matters;

- second, the Review’s evidence base and what it found; and

- third, the challenging policy trade-offs the Review identified as being at the core of the system and which we must get right if we are to improve Australians’ quality of life – not just during their retirement.

As many in this room will know, the Review examined the three pillars of the retirement income system: the Age Pension; compulsory superannuation; and voluntary savings, including home ownership.

It looked at each pillar individually and at the system collectively. In doing so it has provided a comprehensive assessment of the system and the outcomes it is delivering for all Australians.

This is vital because it has allowed proper consideration of each pillar within the context of the wider retirement income system. Until now, each pillar was typically assessed in its own right and without consideration of the contribution being made by the other pillars of the system.

It means questions such as adequacy and sustainability can correctly be considered in the context of the system as a whole rather than looked at in isolation.

Establishing a fact base – what did the review find?

The core task of the Review was to establish a fact base of the current retirement income system to improve understanding of its operation and the outcomes it is delivering for Australians.

What then did the Review find?

1 – The system achieves adequate retirement outcomes.

The Review found the three pillars of the system, the Age Pension, compulsory superannuation and voluntary savings deliver adequate incomes in retirement for most Australians and will be viable for generations to come.

In measuring the adequacy of retirement incomes the system delivers, the Review considered that income in retirement should “replace” around 65 per cent to 75 per cent of disposable working life income. This balances living standards over a person’s lifetime, and is in line with the standard used around the world, including by the OECD.

The Review’s evidence suggests that current retirees meet this benchmark, and that future retirees are also projected to meet it – and in many cases exceed it.

The results are consistent across men and women, different incomes, different work patterns and different savings behaviours. The current retirement income system provides an adequate retirement for a wide range of people.

This is a key finding that should reassure the vast majority of Australians that our retirement income system is working to ensure that their living standards in retirement will broadly reflect their living standards pre-retirement.

In the words of the Review: “Most recent retirees are estimated to have adequate retirement incomes”, and for future retirees, “replacement rates are projected to exceed or meet the [adequacy benchmark] for all income levels when considering employees regardless of relationship status or gender.”

2 – The Age Pension is central to our system and is working effectively.

The Review also found that the Age Pension plays a central role in our retirement income system. It is both a safety-net and a supplement. It allows Australians to more confidently use their own savings during their retirement in the knowledge that that Age Pension is there as a back-stop later in life as their savings are drawn down.

Importantly, the Review also finds the Age Pension plays an important role in improving equity by reducing income inequality among retirees, as low-income retirees receive the largest Age Pension payments.

In adequacy terms, the Review finds that 11 per cent of retirees are in financial stress, lower than the working-age average. To quote the Review, “the Age Pension combined with other support provided to retirees, is effective in ensuring most Australians achieve a minimum standard of living in retirement in line with community standards.”

Notwithstanding the strong endorsement by the Review of the vital role played by the Age Pension, research commissioned by the Review shows that most young people do not think the Age Pension will be there when they retire.

Clearly we must do more to reassure all Australians that this concern is unfounded. The Review’s findings could not be clearer. The Age Pension is well targeted and sustainable and will remain a key pillar of our system for generations to come.

This leads me to the next key finding of the review which is that the retirement income system is both sustainable and robust.

3 – The retirement income system is sustainable and robust.

In the words of the Review, “the Australian retirement income system is effective, sound and its costs are broadly sustainable.”

The cost of the Age Pension is projected to decline from 2.5 per cent of GDP in 2020 to 2.3 per cent of GDP in 2060. And while the cost of superannuation tax concessions will grow from 2 per cent of GDP to 2.6 per cent over that time, the overall cost of the retirement income system will continue to be relatively low by international standards.

This is remarkable given our ageing population. But the cost-effectiveness of our system is not an accident. It is the product of sound design and prior reforms that have enhanced its sustainability. That includes this Government’s reforms to the Age Pension assets test and the introduction of the transfer balance cap for superannuation.

This means, unlike a lot of other countries around the world, we have a retirement income system that is both sustainable today and well into the future.

Along with being sustainable, the Review also showed that our system is resilient. That is, it can continue to provide adequate outcomes for retirees through economic shocks and downturns – including COVID-19.

By way of example, the Review found that even if the market fell by 25 per cent just before they retire, the income for the median earner would only drop one per cent across their retirement, because the Age Pension is available to support them when they need it.

4 – Superannuation plays an important role in the system.

Evidence commissioned by the Review shows compulsory superannuation has increased total household savings. Without compulsory superannuation, many Australians would not save enough for retirement.

The superannuation system also gives people the flexibility to save more if they can. Voluntary contributions to superannuation also provide those outside the compulsory system with an opportunity to contribute, such as the self‑employed and people with interrupted work. Around a quarter of Australians make these voluntary contributions to superannuation.

The benefits of superannuation will grow as the system matures. Median balances for people entering retirement today are around $140,000 but by 2060 are projected to be around $450,000, in real terms adjusted for changes in living standards.

With effective use of those savings, Australians will be increasingly well-placed to achieve financial security in retirement.

5 – Home ownership is critical to quality of life in retirement.

The Review found home ownership was the most important factor for avoiding hardship in retirement. For example, 6 per cent of couples that are homeowners in retirement report being in financial stress. This compares with 34 per cent for couples that rent.

Home ownership lowers living costs and provides financial security in retirement. The Review also found that the home makes up the largest share of wealth for older Australians. This wealth gives retirees peace of mind, and can help retirees cope with spending pressures that they may face.

The Government recognises the importance of home ownership to the financial security and wellbeing of Australians in retirement. To that end, we are continuing to deliver measures that will allow more Australians to buy their first home sooner, including through the First Home Loan Deposit Scheme, First Home Super Saver Scheme and HomeBuilder Scheme.

We are also leveraging the retirement income system to improve supply through the downsizer contribution, which allows people aged over 65 to contribute up to $300,000 to superannuation if they sell their home.

6 – The system is complex and we all need to do more to help Australians make better decisions

While these key findings are overwhelmingly positive, the Review also found that complexity, low financial literacy and limited guidance means too many Australians don’t plan for their retirement or make the most of their savings when in retirement.

Further, many are also not aware of the extensive support they receive from Governments once in retirement, such as through health and aged care services.

The Review considers these factors to be a driver of conservative spending behaviours and misconceptions around how much savings Australians need in retirement to sustain their standard of living.

Improving retirees’ understanding of the retirement income system can assist them to make better use of their retirement savings and improve their living standards in retirement – without sacrificing their living standards during their working life.

This will continue to be an area of focus for the Government.

This is also why the Government’s Retirement Income Covenant is an important reform to the system. The Covenant will establish a requirement for superannuation trustees to develop a retirement income strategy for members. In doing so, the Covenant will require superannuation funds to consider the retirement income needs of their members and how they can assist them to get the most out of their accumulated savings over the course of their retirement.

It is a system that must carefully weigh a series of trade offs

While the Review’s key findings should rightly give us all confidence about the outcomes that the system is delivering as a whole, it also makes clear the difficult trade-offs that are at the core of the system.

These trade-offs represent the key choices that both individuals and Governments must make. And like all trade-offs, there are competing interests that need to be weighed.

The retirement income system is by definition, designed to provide retirement incomes. But the system cannot solely be about maximising income in retirement. Were it to seek to do so, it would clearly come at considerable expense to individuals during their working lives.

The Review rightly outlined that the system should help people balance their lifetime income. This means balancing the trade-offs between income in someone’s working life and in retirement.

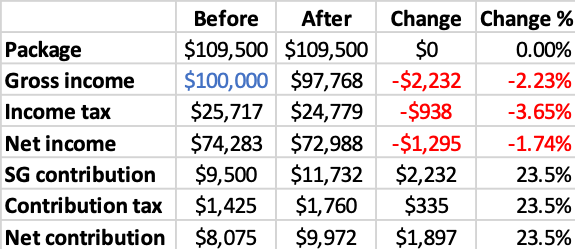

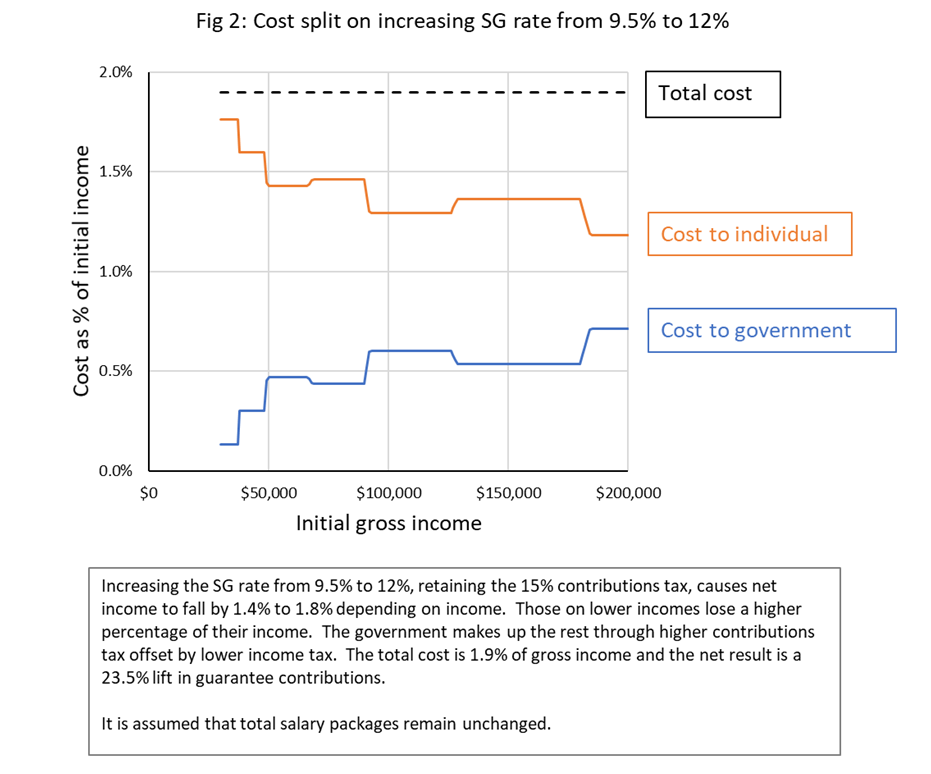

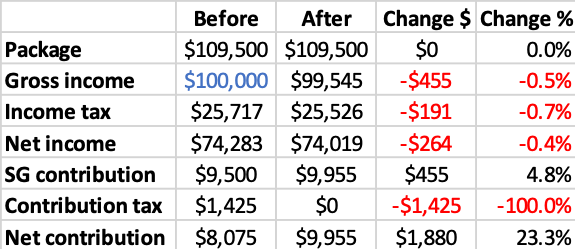

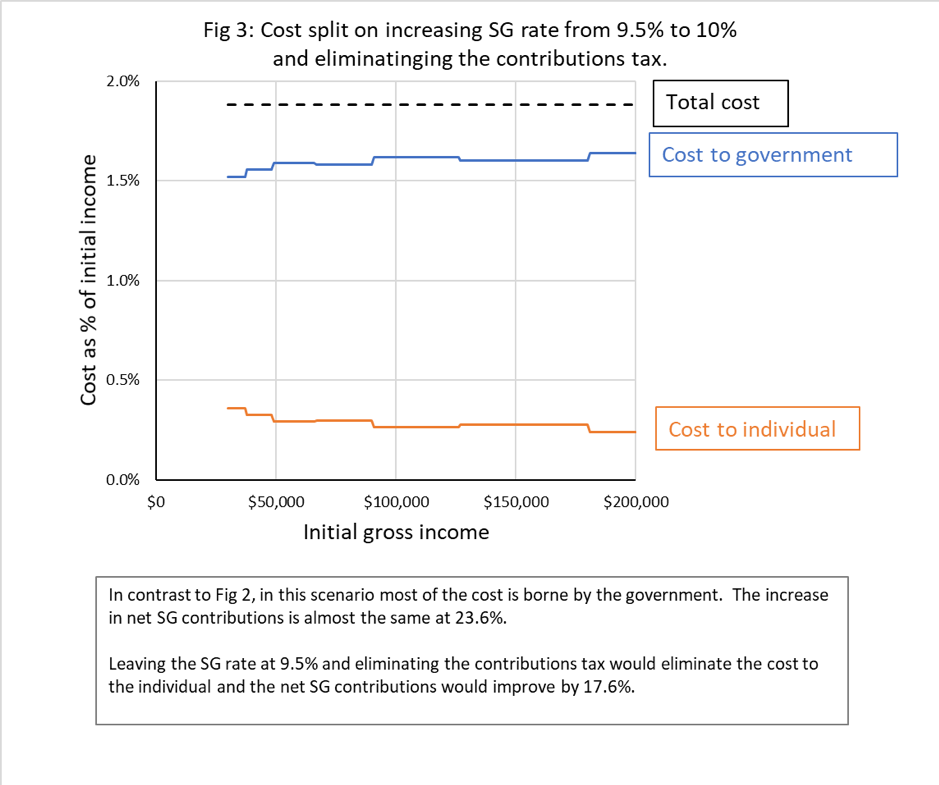

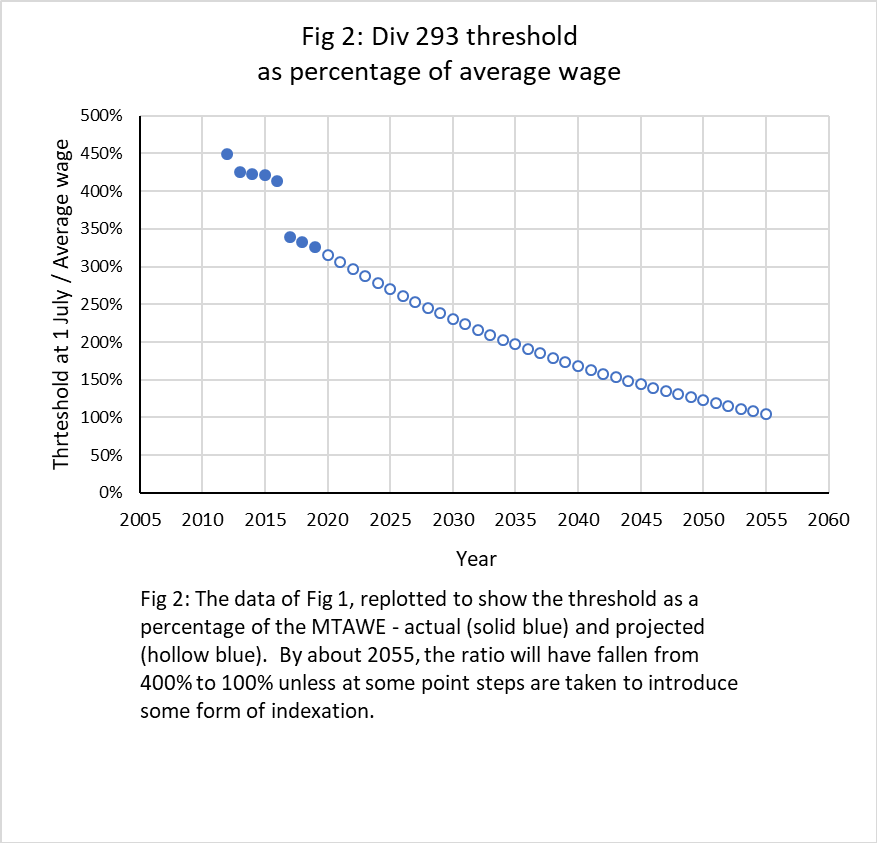

In this respect, the Review highlighted the trade-off between the superannuation guarantee and wages.

Drawing on overwhelming international and Australian evidence including independent analysis from the ANU, the Grattan Institute and the RBA, the review conclusively stated that a higher superannuation guarantee means lower wages for employees.

Specifically, the Review stated “the weight of evidence suggests the majority of increases in the superannuation guarantee come at the expense of growth in wages.”

No-one should be surprised by this or find it controversial. It was part of the original policy design of the superannuation system.

As I have said previously, this is not rocket science, anybody who denies that there is a trade-off is effectively a “flat-earther”.

The Review found that increases to the superannuation guarantee boost retirement income, but that this comes at the expense of working-life income.

For a median earner, increasing the superannuation guarantee could increase their retirement income by $33,000, but lower their working-life income by around $32,000.

Given the compulsory nature of superannuation, this is a trade-off that the system imposes, not one which individuals can choose for themselves.

Were it not for compulsion, it would be a matter for each individual to decide how much of today’s income they are prepared to save for their retirement.

It is simply not true, as some would have us believe, that there is virtually no limit to how high the superannuation guarantee can be increased in the name of delivering ever higher retirement incomes.

Indeed, for some, there isn’t a problem that cannot be solved through a higher rate of compulsory superannuation.

These myths do nothing to help Australians plan for retirement, to feel more confident or to be more secure in their retirement.

Indeed, as the Review noted, the people most affected by high default settings are not the most-well off: “People with lower incomes are particularly vulnerable when compulsory savings rates are set too high”, noting that it “could increase pressure on lower‑income earners during working life through lower incomes”.

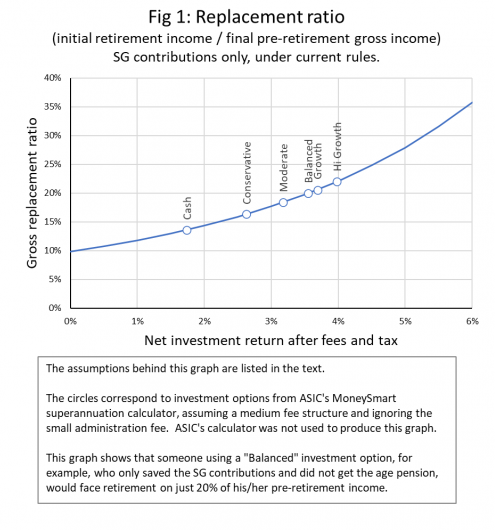

This important observation sits alongside a key finding of the Review with respect to superannuation, which is that “If people efficiently use their assets, then with the SG rate remaining at 9.5 per cent, most could achieve adequate retirement incomes when combined with the Age Pension. They could achieve a better balance between their working life and retirement incomes.”

This is why, as the Prime Minister and I have said, we must rightly carefully consider the implications of the legislated increase to the superannuation guarantee before 1 July this year – even more so at a time when our economy is recovering from the largest economic shock since the Great Depression.

The Review also identified the trade-off between flexibility and compulsion.

The Review noted that our system has considerable flexibility if you want to save more for your retirement. But there is very limited flexibility if a person needs to save less to maintain their quality of life today.

The COVID-19 early release of superannuation scheme was an example of how greater flexibility can benefit those that need it.

Recognising the trade-offs, we gave Australians the choice of increased flexibility, allowing them to access their savings when they needed them most.

And the scheme improved their lives. The ABS Household Impact survey showed that for around 80 per cent of people, the main use of the funds was to pay for bills, mortgages or add to savings.

Early release of superannuation in many cases allowed people to stay in their homes, keep their kids in school and provide for their families during an exceptionally challenging period in their lives.

And, as the Review found, because of our robust multi-pillar system even a person who accessed the maximum $20,000 today will still have an adequate income in retirement.

While compulsion will remain an important part of our system, providing Australians with more flexibility should not be seen as an attempt to undermine the system overall. Far from it.

The earlier Australians interact with the system the more engaged they will be and the more ownership they will feel over their own savings.

More flexibility also means better accommodating the many different circumstances Australians finds themselves over the course of their lives – whether it be their working patterns, taking time off to raise children or deciding to make catch up contributions at a time that their financial circumstances allow.

This is why we have introduced several changes over recent years to provide greater flexibility and allow Australians to make the most of their circumstances and better balance their working life income and their retirement income.

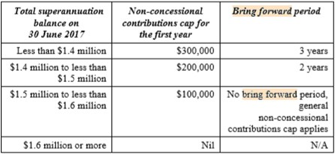

These changes have included allowing Australians with balances under $500,000 to make ‘catch-up’ contributions, enabling the self-employed and others to claim tax deductions for their personal superannuation contributions, and allowing Australians aged 65 and 66 to make voluntary superannuation contributions without meeting the Work Test.

The Government will always be very sceptical of those who, in pursuit of their own self-interest, would seek to restrict the legitimate choices Australians should have about how they choose to save for their own retirement.

Better use of superannuation savings critical to higher retirement incomes

The Review made clear that how retirees use their superannuation savings in retirement has a significant impact on their retirement income and therefore their quality of life in retirement.

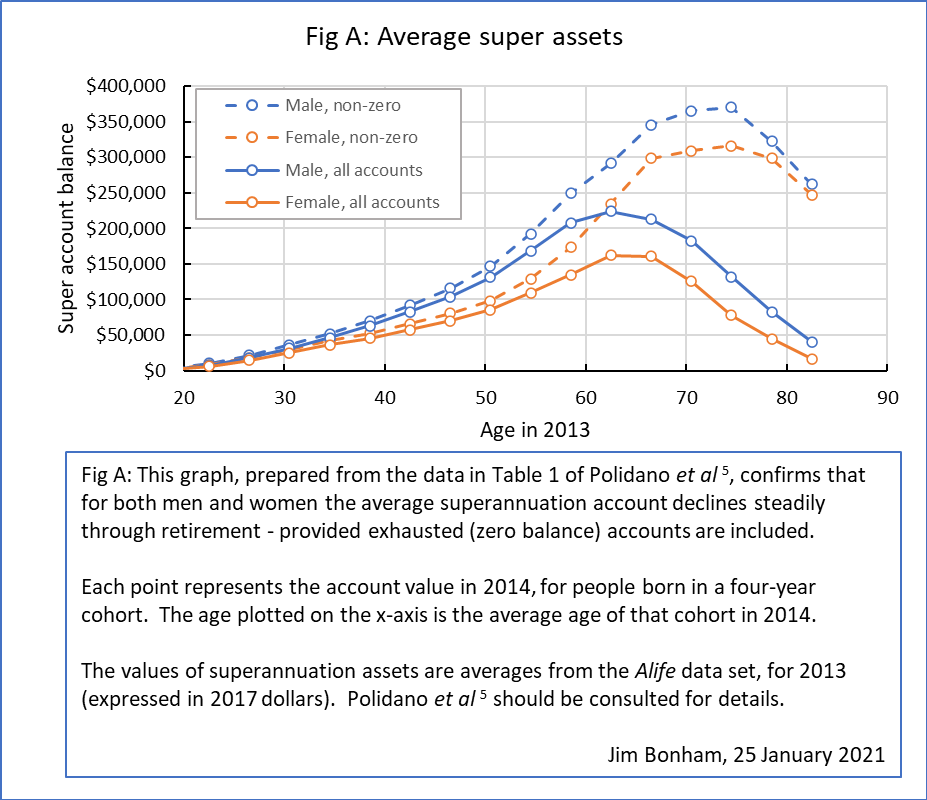

Overwhelmingly, retirees currently do not spend all their superannuation before they die. This is despite the fact that retirees today have not benefitted from a mature superannuation system their whole working life.

The Review shows that if nothing changes, by 2060, one in every three dollars paid out of superannuation will be part of a bequest. This raises the question as to whether the answer to lifting the retirement incomes of Australians is more superannuation savings or better guidance about how to maximise their superannuation savings during their retirement.

This question is all the more important given the trade-offs from higher contributions I have outlined above.

Drawing from the analysis in the Review, Treasury has estimated that at the current superannuation guarantee rate, using superannuation efficiently could increase the median person’s income in retirement by over $100,000 compared to how people typically draw down on their superannuation now.

To illustrate how significant this finding is, the Review also assessed the impact on retirement incomes of the superannuation guarantee rate increasing to 12 per cent, but the same median income earner only drawing down on their superannuation at the current typical rates. In this scenario, the person would only receive $7,000 in additional retirement income over their retirement despite having foregone more of their working life income.

It is clear that giving more confidence and guidance to retirees to assist them in drawing down on their superannuation savings more effectively is critically important.

This is perhaps the key challenge that the Review has highlighted and which we must collectively solve. There are few more effective ways to improve the quality of life for Australians in retirement than to help them make better financial decisions. This is an area that the Government will look to do more and I look forward to engaging with all of you on this critical task.

Continued superannuation reform key to higher retirement incomes

The efficiency of the superannuation system is vital to the retirement outcomes it delivers Australians. Under a compulsory system supported by important tax incentives, it is incumbent on the Government to ensure that members and taxpayers are getting value for money from the system.

The Government has successfully implemented major reforms to the system over recent years that will see substantial savings flow to Australians.

These reforms have included fee caps on low balance superannuation accounts, banning exit fees and requiring insurance to be offered on an opt-in basis in certain circumstances where it would otherwise result in an unwarranted erosion of member balances.

The Government has also legislated reforms to allow the ATO to proactively reunite lost and unclaimed super balances held by the ATO with an individual’s current active account. As of December 2020, the ATO has proactively consolidated $3.7 billion held in unintended multiple accounts on behalf of almost two million Australians.

As the Review highlights, adequate retirement outcomes are also a product of the returns Australians earn on their savings. Those returns are a function of the performance their superannuation fund delivers and the costs of delivering that performance.

That is why the Government is focussed on ensuring Australians’ hard earned superannuation savings are working harder for them. As many in this room will be aware, the Your Future, Your Super reforms announced in the Budget stand to boost the retirement savings of millions of Australians, with Treasury estimating a total benefit to members of $17.9 billion over 10 years.

Treasury estimates young workers entering the workforce could be up to $98,000 better off at retirement because of these reforms.

Eliminating expenditure that is not in the best financial interests of members, preventing the creation of unintended multiple accounts, driving down fees and holding funds to account for poor performance represents the only “free lunch” when it comes to increasing the retirement incomes of all Australians.

Closing remarks

To conclude, the comprehensive review of Australia’s retirement income system tells us that we have much to celebrate.

Our system produces adequate retirement incomes for the vast majority of Australians, and it does so in a way that is fiscally sustainable in the long term.

As our population ages, as we live longer and our retirement patterns change, I am confident that the pillars of the system will continue to provide effective support to Australian retirees.

But as the Review highlights, there is scope to improve the system and to continue to challenge ourselves with respect to the key trade-offs at the core of the system.

The work of the Review now provides the evidence base to have these discussions and to consider what more we need to do to improve the system and ultimately help more Australians more effectively balance their lifetime incomes.

Wednesday, March 3, 2021