Author's posts

Super effort to achieve what workers really want

The Australian

30 November 2019

Judith Sloan – Contributing Economics Editor

It was all going so well for the industry super funds. The election of a Labor government and they would be home and hosed.

There would be no talk of cancelling or deferring the legislated increase in the superannuation contribution rate from 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent. Those pesky requests to improve the governance of the funds by having more independent trustees would fade away.

Life and total and permanent disability insurance would remain an effective compulsory part of superannuation; after all, the opt-out arrangement had been introduced by Bill Shorten when he was the responsible minister. There would be some pretence about dealing with multiple accounts but no real action.

As for removing the quasi-monopoly position of industry super funds nominated as default funds in the modern awards, all discussion would abruptly end. And why would the ambition end there? Fifteen per cent sounds better than 12 per cent when it comes to a guaranteed regular flow of money to the funds.

All those dreams are now a fading memory as industry super funds confront a government that is not entirely convinced of the rationale for compulsory super and is determined to fix problems in the system that disadvantage far too many workers and retirees.

We don’t hear so much these days about our superannuation system being the envy of the world.

These claims were always made by those with deep vested interests in the system; in particular, the vast industry that hangs off the management of funds and their administration.

Some of the core problems of our superannuation system have been highlighted by various reports of the Productivity Commission. They include:

• The unclear purpose of superannuation.

• The excessive costs attached to investment and administration.

• The problem of multiple accounts leading to balance erosion.

• Unwanted (and sometimes worthless) insurance.

• Unaccountable governance with too many trustees having inadequate skills.

• The continuation of poorly performing funds.

Don’t get me wrong; superannuation has been a great product for some people, most notably those with earnings in the top quarter of the distribution. However, this observation is not sufficient to justify a system of compulsory superannuation. Moreover, it is clear any savings on the age pension have to be weighed against the cost of the variety of superannuation tax concessions that apply.

It also needs to be noted here that, on average, the investment performance of the industry super funds has been very good and superior to most retail funds, although there is the qualification of the absence of like-with-like comparison. Self-managed superannuation funds also generally have produced very good returns.

The government has been attempting to deal with some of the problems in the system after the remedial efforts that were made in its previous term were largely thwarted. Two changes have been implemented to merge inactive low-balance accounts with active ones and to make insurance an opt-in product for young workers and for those with low-balance accounts. Both changes were opposed by the industry super funds.

Neither of these changes deals comprehensively with the problems of multiple accounts or forced insurance but they are a start. More surprising have been the recent boasts of Superannuation, Financial Services and Financial Technology Assistant Minister Jane Hume about recent merger activity of industry super funds. Examples include the linking of Hostplus with Club Super and First State Super with VicSuper. Certainly the issue of failed mergers was raised in the Hayne royal commission into banking.

However, the issue of fund consolidation is actually two separate issues. One relates to funds that are clearly of sub-optimal size, leading to a failure to capture economies of scale. The second is about poorly performing funds and the need to remove them from the pool of default funds.

The work of the Productivity Commission makes it clear that a member who lands in a poorly performing fund and stays there by dint of inertia stands to lose up to several hundreds of thousands of dollars in terms of the final balance. It’s not apparent, however, whether the recent spate of fund mergers will deal with the problem of poorly performing funds.

In the meantime, the mergers of some large industry super funds could potentially lead to an anti-competitive configuration of a small number of behemoths that will be able to dictate many aspects of corporate behaviour given their large shareholdings. It’s hard to see how the government would regard this as a desirable outcome.

The hottest topic in superannuation remains the fate of the legislated increase in the superannuation contribution rate. Unless the statute is changed, this rate will be ratcheted up by 0.5 percentage points every year from July 1, 2021. A rate of 12 per cent will apply from July 1, 2025.

Every annual increase will cost the government about $2bn a year in forgone revenue given the cost of the tax concessions. This is a significant sum in the context of the likely tight position of the budget in that period.

The superannuation industry is highly committed to these legislated increases going ahead. Some absurd pieces of research have been released to suggest that higher superannuation contribution rates do not involve any reduction to wage growth, something that is contradicted by the theory and actual practice, including on the part of the Fair Work Commission.

In the context of low wage growth, it will be a big call by the government to ask workers to forgo current pay rises in exchange for higher superannuation balances in several decades.

Moreover, for many workers, these higher superannuation balances will simply have the effect of knocking off their entitlement to the full age pension. For them, compulsory superannuation is effectively just a tax — lower current consumption now and the loss of the full age pension in the future. It’s not clear what the government’s real thinking on this important matter is. The Prime Minister and Treasury are maintaining their support for the legislated contribution increase but may be happy to include the Future Fund in the mix of investment options to improve the competitiveness of the industry.

Other members of the government favour a cancellation of the increase or smaller rises across a longer timeframe. There is also some support for making the increase voluntary; workers could choose between a current pay rise or a higher super contribution rate.

The bottom line is that superannuation remains a dog’s breakfast from a policy point of view. The government has made some small strides to improve some aspects of the system, but the high fees and charges imposed by the funds remain a significant issue.

Far from being the envy of the world, it has become apparent that our system of compulsory superannuation was a serious policy error enacted for short-term reasons to fend off a wages explosion. It may be too late to turn back but thought needs to be given to significantly reforming the system in ways that reflect the preferences of workers as well as generating a better deal for taxpayers.

Retiree time-bombs

By Jim Bonham and Sean Corbett

1 Abstract

The complexity of superannuation and the age pension conceals at least 6 time-bombs – slowly evolving automatic changes to the detriment of retirees – caused by inconsistent indexation: Division 293 tax, currently only for high income earners, will become mainstream.Shrinking of the transfer balance cap relative to the average wage (which is a measure of community living standards) will reduce the relative value of allocated pensions.Shrinking of the transfer balance cap, relative to wages, will increase taxation on superannuation in retirement. Prohibiting non-concessional contributions when the total superannuation balance exceeds the transfer balance cap will constrict superannuation balances more over time.The age pension will become less accessible, as the upper asset threshold shrinks relative to wages.Part age pensions, for a given value of assets relative to wages, will reduce.

2 Introduction

The Terms of Reference of the Review of the Retirement Income System require it to establish a fact base of the current retirement income system that will improve understanding of its operations and outcomes.

Important goals are to achieve adequate retirement incomes, fiscal sustainability and appropriate incentive for self-provision. The Retirement Income System Review will identify:

- “how the retirement income system supports Australians in retirement;”

- “the role of each pillar [the means-tested age pension, compulsory superannuation and voluntary savings, including home ownership] in supporting Australians through retirement;”

- “distributional impacts across the population over time; and”

- “the impact of current policy settings on public finances.”

For the detailed Terms of Reference follow the link at https://joshfrydenberg.com.au/latest-news/review-of-the-retirement-income-system/.

Terrence O’Brien and Jack Hammond have made a number of suggestions for the Review to consider (https://saveoursuper.org.au/save-our-super-suggestions-for-review-of-retirement-income-system/). In particular, at the close of their paper they wrote:

“9. Let the modelling speak

“Only long-term modelling can show which measures are likely to have the best payoffs in greatest retirement income improvements at least budget cost. Choice of which measures to develop further are matters for judgement, balancing the possible downside that extensive policy change outside a superannuation charter may only further damage trust in retirement income policy setting and in Government credibility. “

This paper expands on that point, by presenting the results of straightforward but informative modelling which shows how the age pension, superannuation and voluntary savings (including home ownership) operate and interact – particularly over extended time periods.

A disturbing problem, because it is not obvious, arises from the inappropriate, or no, indexation of various parameters within both the superannuation system and the age pension system. This was briefly mentioned by Sean Corbett (https://www.superguide.com.au/retirement-planning/politician-greed-destroying-super), but has otherwise gained little or no attention.

Over the medium to long term, this inappropriate indexation will result in higher taxation, reduced age pension and superannuation for many people and a generally worse retirement outcome. If this is the deliberate intent of the government, it should be declared. Otherwise the problem should be corrected.

These indexation issues are the retiree time-bombs. The Review must come to grips with them, whether or not they are intentional, and they are the focus of this paper.

3 The importance of the average wage

The impact of superannuation on an individual typically extends from the first job, through retirement to death; or perhaps even further until the death of a partner or another dependent. For many, the age pension provides critical income through all or part of their retirement.

Accordingly, formal analysis of retirement funding often must extend over many decades, making suitable indexation an extremely important matter.

The full age pension is indexed to the Consumer Price Index (CPI) or the Pensioner and Beneficiary Living Cost Index, or to Male Total Average Weekly Earnings (MTAWE) if that is higher, which it usually is. In May 2019 MTAWE was $1,475.60 per week or approximately $76,730 per annum.

This method of indexing is intended to allow retirees receiving a full age pension to maintain their living standard relative to that of the general community – MTAWE being taken as an indicator of that standard – and it is critical to the design of the full age pension.

For long term modelling ASIC’s Money Smart superannuation calculator suggests a combination of 2% for CPI inflation, plus 1.2% for rising living standards, giving an inflation index of 3.2% (https://www.moneysmart.gov.au/tools-and-resources/calculators-and-apps/superannuation-calculator). In this paper, that figure of 3.2% is assumed to represent future wages growth.

This is a modelling exercise, not a prediction, so the precise value of wages growth assumed in this paper is not particularly important – use of a somewhat different figure would only change details, not the big picture – but the distinction between CPI growth and wages growth is important, the latter usually being higher.

4 Division 293 tax

Division 293 tax (see https://www.ato.gov.au/Individuals/Super/In-detail/Growing-your-super/Division-293-tax—information-for-individuals/) is a good place to begin this analysis because the problem is straightforward.

Division 293 tax has the effect of increasing the superannuation contributions tax for high income earners. The details don’t matter here, as we are only concerned with the threshold: $300,000 when the tax was introduced in 2012, subsequently reduced to $250,000 in 2017.

During this period the average wage has been rising steadily, which means the reach of this tax is extending further and further down the income distribution. Eventually, if the threshold is not increased, it must reach the average wage, by which time Division 293 will have become a mainstream tax.

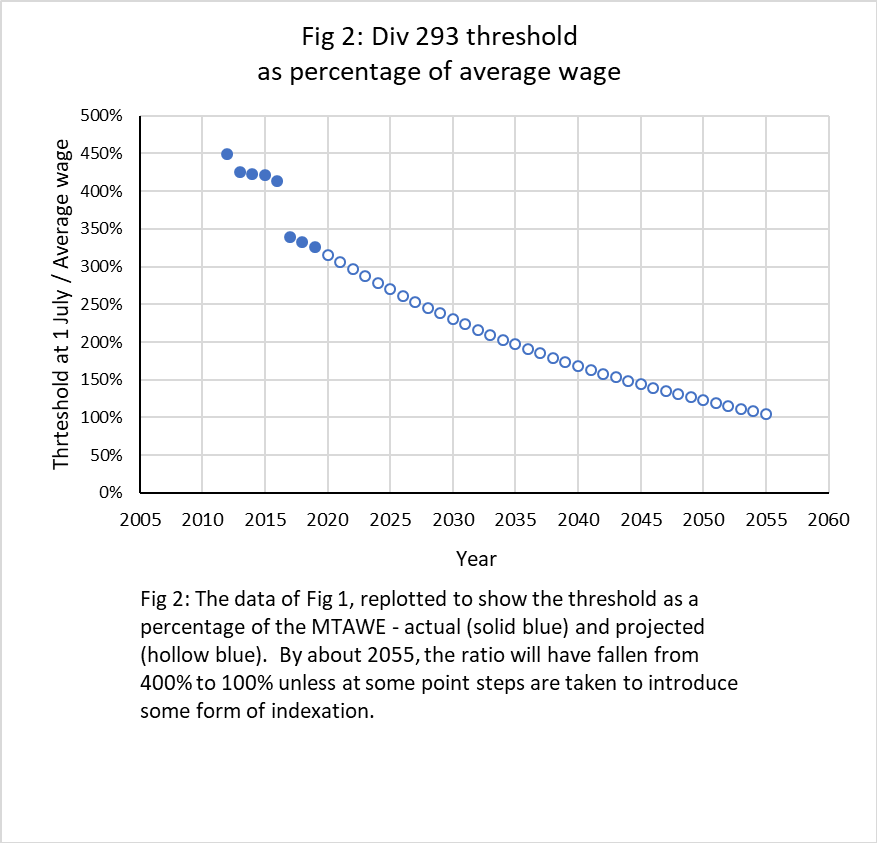

Fig 1 shows the actual and projected values (in nominal dollars) of the tax threshold and of the average wage. The two are projected to be roughly equal within about 30 years.

If Labor had been successful in the 2019 election, the Division 293 threshold would have been further reduced to $200,000 so that, barring further changes, it would have been equal to the average wage in about 25 years.

Fig 2 shows the same data replotted by dividing the Division 293 threshold for each year by the average wage for that year and expressing the result as a percentage. Expressing data relative to the average wage in each year, as in Fig 2, is often an informative way to show long term trends.

If the Division 293 threshold remains unchanged in nominal dollars, it will continue to decrease relative to the average wage, and so a greater percentage of taxpayers will be caught each year. They will find their after-tax superannuation contributions, and hence their balance at retirement, will decrease as will their subsequent retirement income from superannuation.

This will reduce the effectiveness of superannuation as a long-term savings mechanism. People’s confidence in superannuation will be eroded, as it thus becomes less effective.

Failure to index the Division 293 threshold to wages growth (which would confine its effect to the same small percentage of high wage earners in future years) is taxation by stealth and makes it the 1st time-bomb.

The very simple solution is for the government to commit to indexing the Division 293 threshold in line with wages growth.

5 The transfer balance cap

5.1 The value of allocated pensions

The transfer balance cap, currently $1.6 million, is the maximum amount with which one can start a tax-free allocated pension in retirement. Any additional superannuation money must either be withdrawn or left in an accumulation account where taxable income is taxed at 15%.

Unlike the Division 293 threshold the transfer balance cap is indexed, but it is indexed to CPI inflation (assumed to be 2% in this paper) rather than to wages (3.2%), and adjustments are only made in $100,000 increments.

Indexing the transfer balance cap to CPI means that over time the starting value of an allocated pension account will become lower relative to the average wage, because the latter rises faster.

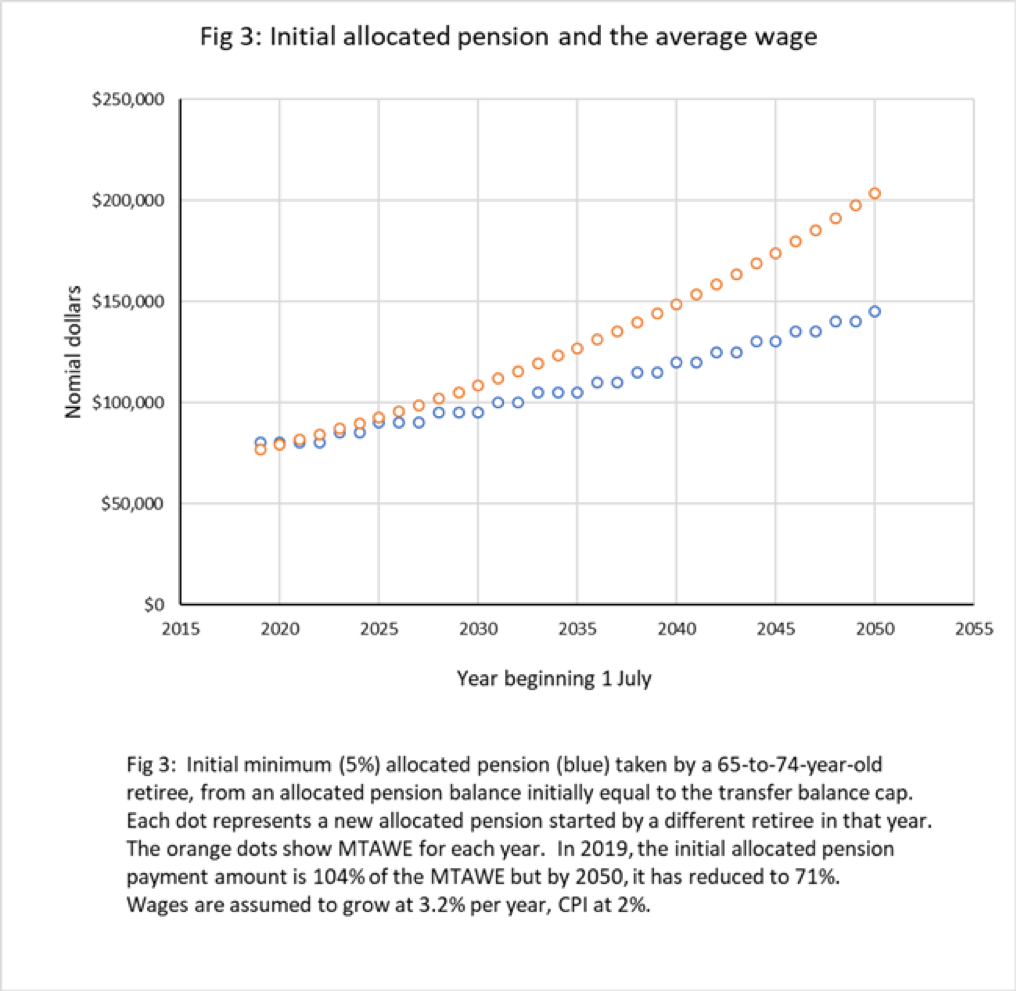

This is illustrated in Fig 3, where projected values of MTAWE are shown in orange; and the minimum (5%) allocated pension drawn by someone starting retirement at age 65-74, with an allocated pension account balance equal to the transfer balance cap, is shown in blue.

Despite the fact that the minimum allocated pension payment amount increases every couple of years, the average wage increases faster.

The following table shows some of the data behind Fig 3, for someone age 65 to 74 retiring in 2019, compared to retirement in 2050:

| Year | Transfer Balance Cap | Allocated Pension (AP) | MTAWE | Ratio AP/MTAWE |

| 2019 | $1.6 m | $80,000 | $76,730 | 104% |

| 2050 | $2.9 m | $145,000 | $203,724 | 71% |

This is a big drop in relative living standard for superannuants: 104% of MTAWE in 2019 down to 71% in 2050.

This degradation, relative to community living standards, of the allocated pension provided by the transfer balance cap is the 2nd time-bomb for the transfer balance cap.

5.2 Taxing super in retirement

Because the transfer balance cap will grow more slowly than wages, one expects that in the future an increasing proportion of a retiree’s superannuation will be held in taxable accumulation accounts rather than in tax-free allocated pension accounts.

This is another instance of taxation by stealth. It is the 3rd time-bomb.

5.3 Non-concessional contributions

Non-concessional contributions (from post-income-tax money) are currently limited to $100,000 per annum. That limit is indexed to wages growth, like the $25,000 limit on concessional (pre-tax) contributions.

However, non-concessional contributions are only permitted when the total superannuation balance is less than the transfer balance cap which, as we have seen, is indexed to CPI. The effect of this indexation mismatch is that the ability to make non-concessional contributions will automatically shrink, relative to wages and living standards, in the future. Those who rely on substantial non-concessional contributions late in their working life will be particularly affected.

This is the 4th time-bomb.

6 The age pension

6.1 Basic structure

The age pension is indisputably complicated, and a brief review may be helpful.

Detailed descriptions can be found at

https://www.humanservices.gov.au/individuals/services/centrelink/age-pension

https://www.dss.gov.au/seniors/benefits-payments/age-pension

https://www.dss.gov.au/benefits-payments/indexation-rates-july-2019

A somewhat simplified description is as follows:

The full pension for a member of a couple is lower than for a single person.

The full pension is reduced by the application of tests on assets and incomes – whichever test gives the greater reduction is the one that applies.

Assets reduce the age pension by $78 per annum per thousand dollars’ worth of assets (often expressed as $3 per fortnight per $1,000) above a threshold.

Despite frequent claims to the contrary, including on the Human Services website quoted above, the retiree’s home is assessed by the asset test.

The assessment is achieved by applying an asset test threshold which is lower for homeowners than for renters (currently by $210,500 for singles), but the effect is exactly the same as using the renter threshold and treating the home as a non-financial asset worth $210,500 – indexed to CPI.

Regardless of how the process is defined mathematically, claiming that the home is not assessed is simply false.

Income reduces the age pension by 50 cents per dollar of income earned above a threshold, except that

- The first $7,800 per annum of employment income is not counted

- Income from financial assets (bank accounts, shares, superannuation accounts etc) is deemed to be 1%, for asset value below a threshold, and 3% above that; then the deemed income is used in the income test.

The full age pension, for singles or members of a couple, is usually indexed to MTAWE as discussed previously. Every other relevant figure (the income test deeming threshold, the asset test threshold, the assumed value of the home – or, equivalently, the homeowner’s asset threshold) is indexed to CPI.

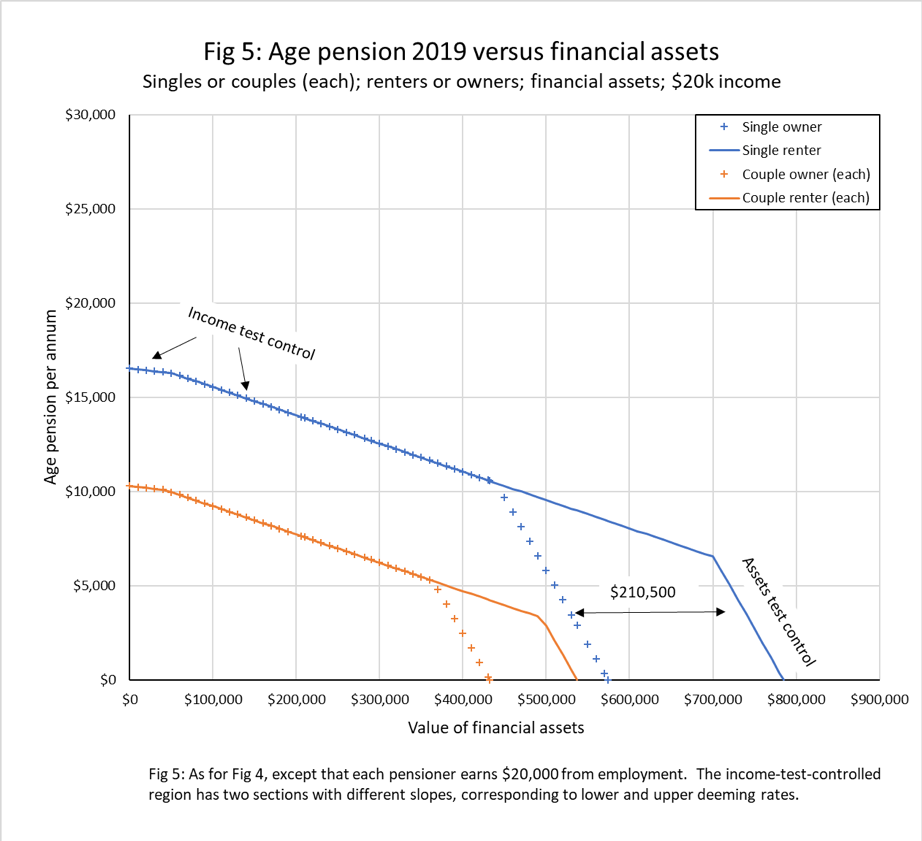

Apart from the home, the most significant asset which pensioners own is likely to be their financial assets, so a convenient way to describe the age pension graphically is to plot the value of the pension against the value of financial assets – as shown in Fig 4 for a single renter and for a homeowner, with no significant assets or income other than the financial assets.

Additional non-financial assets would shift the asset-test-controlled region further to the left. Additional income lowers the income-test-controlled part of the curve. For example, in Fig 5, each person is assumed to earn $20,000 per year.

Graphs such as Fig 4 allow visualisation of the complex behaviour of the age pension, which can otherwise be very confusing. For example, a quick glance at Fig 4 shows that for the case considered, owning a home will reduce the age pension by nearly $20,000 per year for a single age pensioner with around $600,000 worth of financial assets but the effect is far less with $400,000 worth of assets.

The curves also show the steep asset-test-controlled region, where the age pension decreases at a rate of 7.8% ($78 per annum per $1,000 of assets), which tends to overwhelm the increase in actual earnings from the assets. Although it is a major problem in itself it will not be discussed in detail here, in the interest of brevity.

6.2 The age pension time bombs

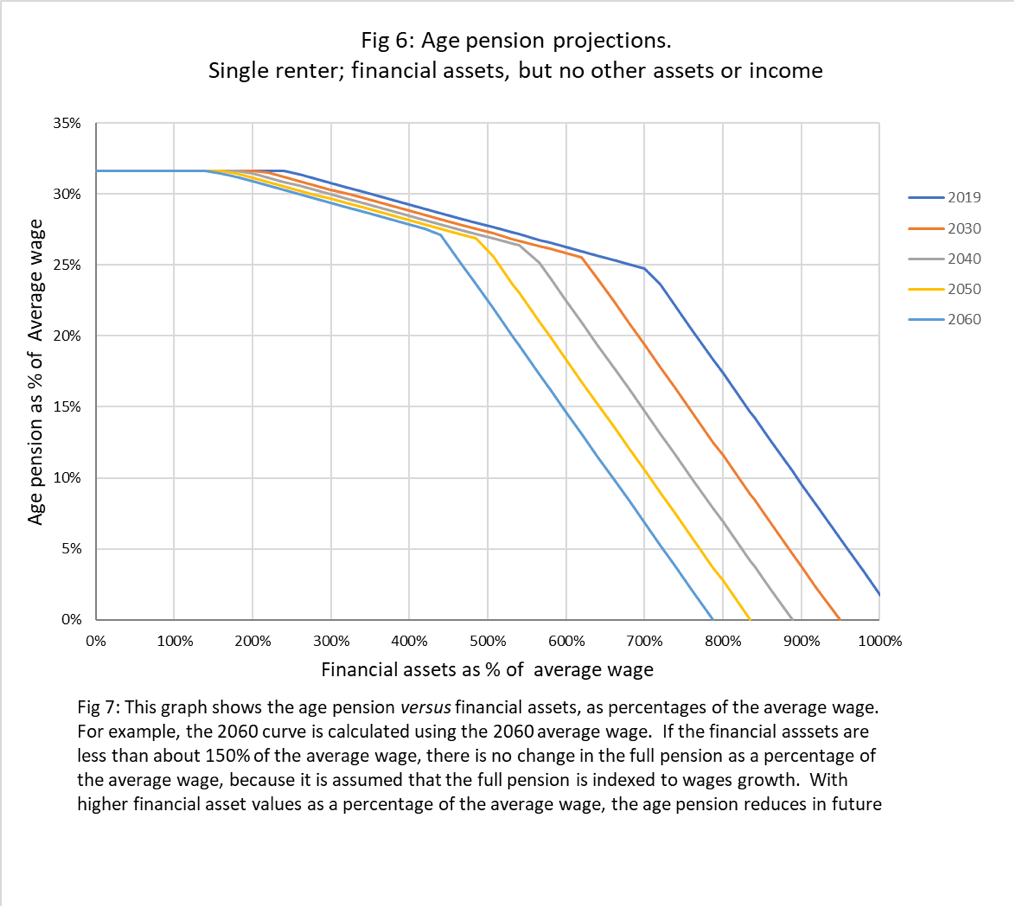

Figs 4 and 5 give snapshots at a particular point in time. To examine the behaviour of the age pension over extended periods, however, it is best to relate asset values and income to the average wage.

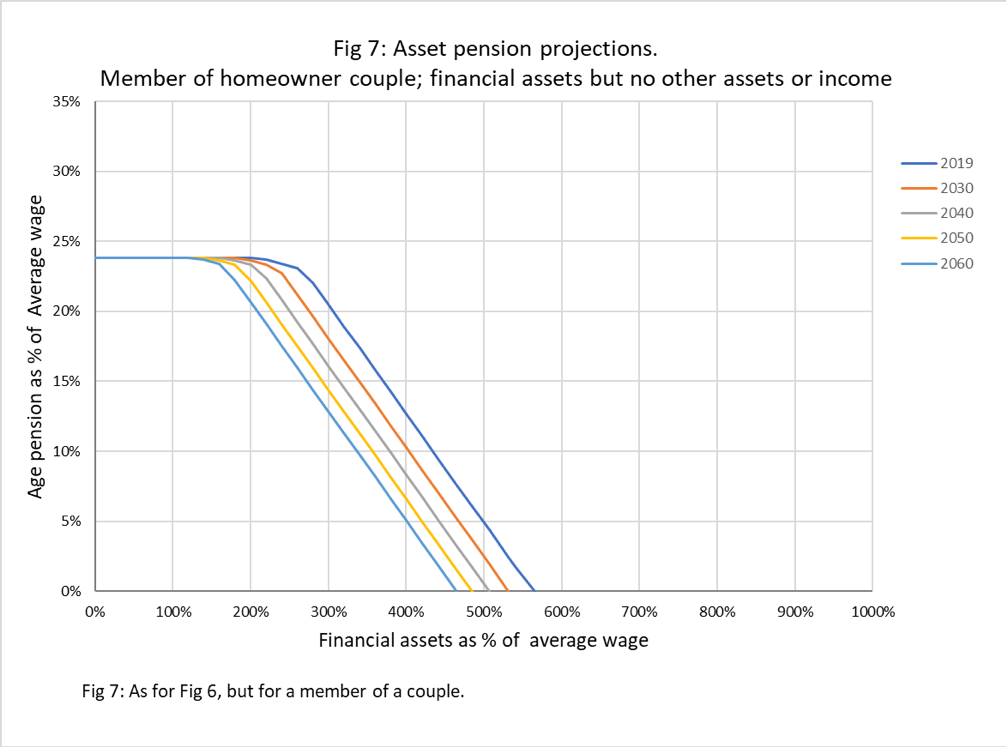

This is done in Fig 6 which shows the projected curves over the next 4 decades for a single renter, with no other assets, and in Fig 7 for a member of a homeowner couple. Note that each curve is calculated using the projected average wage for that year.

Except for part of the full age pension area of the curves, where they all overlap because the age pension is indexed to wages growth, the curves show a steady trend towards lower age pension for a given financial asset base.

Because only the full pension is indexed to wages growth and other parameters are indexed to CPI, it is mathematically inevitable that the structure of the system will automatically change slowly over time. Relative to living standards, as indicated by the average wage:

- Part age pensions will become harder to get, as the upper asset threshold shrinks.

- Part age pensions for a given value of financial assets will reduce.

These are the 5th and 6th time-bombs.

What we are seeing here is universal: if different components of the system are indexed in different ways, the structure of the system will automatically change over time – even if the age pension is radically restructured.

6.3 A case study: effects of indexation on the individual retiree.

It is obvious in Figs 6 and 7 that someone beginning retirement in future years will receive less age pension for a given value of assets, when both are expressed relative to the average wage. i.e. to community living standards.

Fig 7 shows how the 5th and 6th time-bombs work for a specific case: a single homeowner who retires at age 67 with 8 times MTAWE ($614,000 in 2019) in an allocated pension account, from which only the age-based minimum is withdrawn, and who has no other income or assets.

Four cases are shown, for retirement in 2019, 2030, 2040 or 2050.

The allocated pension is assumed to be invested in a “balanced” fund returning 4.8% nominal, less 0.5% investment fees (these values are taken from the ASIC Money Smart superannuation calculator, neglecting the small administration fee).

Because it is assumed that the retiree in each case starts with 8 times MTAWE in the allocated pension account, both the account balance and the minimum withdrawal, as a percentage of MTAWE only depend on age. Thus, there is only one line for allocated pension income in Fig 8. It falls fairly steadily as capital is depleted in the account.

As the asset value falls, the retiree eventually becomes entitled to a part age pension. Starting in 2019, this retiree would begin getting a part age pension within a couple of years. The retiree starting in 2050 would have to wait a few years longer.

Thereafter, the later retiree always gets a lower age pension, relative to MTAWE. The full age pension – which each of these retirees approaches in their early 90s – is, however, constant as a percentage of MTAWE as already discussed.

The cause for the different treatment of full and part age pensioners is that the full pension is indexed to wages growth, while most of the factors controlling the part age pension are indexed to CPI. If Fig 8 is reworked for a different set of assumptions (for initial balance, investment returns and withdrawal rate), the detailed shapes of the curve will alter, but the general conclusions will be unaffected.

The obvious solution is to index all parameters to wages growth, and then all the curves for part age pensions in Fig 8 will be the same and the system will be stable over time.

As it stands, the part age pension is designed to slowly become harder to get, and less generous (for a given asset value relative to living standards) – another demonstration of the 5th and 6th time-bombs.

7 Conclusion

This paper, based on relatively straightforward spreadsheet modelling, has exposed a number of time-bombs in the structure of superannuation and age pension. These time-bombs are not particularly obvious, but they have the effect of surreptitiously increasing taxation, decreasing superannuation pensions and making the age pension harder to get and less generous. This will reduce the prosperity of retirees and hence of the country as a whole.

The time-bombs all have their origin in failing to index all parameters in the same way. The natural choice for an index is wages growth, because that is directly related to living standards, but if some other index is used it is still important that it be used consistently throughout the system to maintain stability.

Even if the superannuation and age pension schemes are radically altered, it remains important to index all relevant parameters in the same way. Otherwise these time-bombs will be inevitable.

8 Disarming the time-bombs

The Review of the Retirement Income System panel is scheduled to produce a consultation paper in November 2019.

The 6 time-bombs discussed in this paper merit consideration because they touch directly on so many of the issues flagged in the Terms of Reference: “adequate retirement incomes”, “appropriate incentives for self-provision”, “improve understanding”, “outcomes”, “the role of each pillar”, “distributional impact … over time” and, most importantly, “establish a fact base”.

Identification of these time bombs is a contribution to the establishment of a fact base on retirement incomes. Fortunately, the time bombs can be disarmed by regularising indexation throughout the superannuation and age pension systems.

30 October 2019

***********************************************************************

Save Our Super suggestions for Review of Retirement Income System

BY TERRENCE O’BRIEN AND JACK HAMMOND on behalf of themselves and Save Our Super

28 June 2019

When more individuals save for self-funded retirement above Age Pension levels, their savings contribute funds and real resources for reallocation through the financial sector to fund investments. Such an economy will be more dynamic and efficient than one which relies more on incentive-deadening taxes for redistribution through the Age Pension.

Table of contents

Save Our Super suggestions for Review of Retirement Income System

Save Our Super offers the following preliminary ideas for the Review of the Retirement Income System. We regard such a review as highly desirable and potentially path-breaking if well directed, but fraught with dangers for the Government and threatened with futility if not properly handled.

1. Embed a clear statement of Government retirement income objectives in the Review’s Terms of Reference

The Superannuation (Objective ) Bill 2016 attempted to legislate an objective for superannuation, as if that would somehow guide future governments’ detailed regulatory and tax decisions for superannuation. It did not identify the objective for the Age Pension, nor explain how the two elements ought to interact in the overall retirement income system.

Both Save Our Super and the Institute of Public Affairs criticised that attempt, and suggested improvements.

The effort to define objectives is much better set in the broader retirement income framework now envisaged.

Saving is a contested issue of philosophical vision.

To most Australians, saving is the process by which those prepared to delay gratification and consumption make real resources available to those with an immediate need for them. Savings are not just a pile of money that Scrooges sit over and count. From the dawn of history, when families saved some of autumn’s grain to provide seed for next spring’s planting, saving in every culture has been the means by which living standards have grown and the next generation has been given more opportunities than their parents.

Saving funds investment. In the modern economy, it provides both the finance and, indirectly, the real resources that are allocated through capital markets to the businesses or loans that produce the biggest increase in the community’s living standards. If Australian investment cannot be financed by Australian saving (either by households, companies or governments running budget surpluses), it has to be financed by borrowing from foreigners or accepting direct foreign investment in Australian projects.

Viewed against that backdrop, household saving is good. Raising household savings, just like eliminating government budget deficits (ie stopping government dis-saving), reduces Australian reliance on selling off assets to foreigners or contracting foreign borrowing. People should be able to save as much as they wish, ideally in a stable government spending, taxation and regulatory structure that does not penalise savings or distort choice among forms of saving. In such an ideal framework, they should be allowed to save for retirement, for gifts, for endowments, for bequests or for any purpose for which they choose to forgo consumption.

Specific tax treatment of long term saving (such as capital gains tax, and tax treatment of the home and superannuation) is necessary to reduce the discouragement to saving from government social expenditures and from levying income tax at rising marginal rates on the nominal returns on saving. But critics regard such specific treatment as ‘concessions’ to be reduced or eliminated. They want to limit what saving can occur, and tax what does occur. Critics think of private saving not as the foundation of investment, but as the wellspring of privilege and intergenerational inequity.

We suggest the Terms of Reference for the Review should in its preamble set the Government’s practical and philosophical aspirations for household saving and the retirement income system. We suggest the preamble to the Terms of Reference should highlight:

- The retirement income system as a whole should aim to ensure that as the community gets richer, retirees should through their own saving efforts over a working lifetime, both contribute to and share in those rising community living standards.

- The Age Pension should be focussed as a safety net for those unable to provide for themselves in retirement because of inadequate periods in the workforce or otherwise limited earnings and saving opportunities.

- As the population ages, superannuation saving for retirement is likely to be a growing part of the national savings effort. Buoyant growth in superannuation finances investment and lending, and helps support rising living standards. (Conversely, a rising dependence on the Age Pension would spell only a higher tax burden).

- The design of the retirement income system must be:

- stable;

- set on the basis of published, contestable modelling; and

- evaluated for the long term, namely, the 40 or so years over which lifetime savings build, and the 30 or so years in which retirees can aspire to enjoy whatever living standards they have saved for.

- The Age Pension and superannuation systems and the stock of retirement savings should be protected as far as practicable by grandfathering assurances against capricious adverse changes in future policy. Such changes create uncertainty and destroy trust in saving and self-provision for retirement.

2. Avoid policy prescription of savings targets or permissible retirement income standards

Some commentators have proposed the idea of a ‘soft ceiling’ on levels of retirement income saving acceptable to policy. That approach derives a level of acceptable retirement income by working backwards from the observed historical pattern of retirees’ spending, which declines with age, especially after age 80. According to those views, the fact that some retirees continue to save even after retirement is regarded as a sign of policy failure and excessively generous tax treatment (rather than of recently rising asset values). Saving is treated, in effect, as allowable to those of working age, but to be discouraged beyond a certain point, and prevented for retirees. According to this analysis, we already have “more than enough” money in retirement.

The Grattan Institute suggests a savings target such that all but the top 20 per cent of workers in the earnings distribution achieve a retirement income of 70 per cent of their pre-retirement income over the last five years of their working lives. For those in the top 10 per cent of the earnings distribution, a replacement rate of 50-60 per cent of pre-retirement earnings is “deemed appropriate”. (Approved retirement income for the second decile is not specified.)

Even after discouraging saving in this way, Grattan also recommends the introduction of inheritance taxes.

The Terms of Reference should make it clear that the Government does not support such ideas. It should emphasise it regards saving for retirement as beneficial to the community, and does not wish to limit it by arbitrary targets.

3. Prevent another ‘Mediscare’

Possible changes to the Age Pension, its means tests, compulsory superannuation contributions, superannuation taxation or regulation will be inevitably contested.

There is now zero public trust in the stability and predictability of retirement income policy. That results from the reversal, in 2017, of Age Pension and superannuation policies which, after extensive research and consultation, were introduced as recently as 2007. In addition, public trust has been eroded by the 2019 Labor election platform to make wide-ranging increases in taxes on long-term savings (that is, the Capital Gains Tax, franking credit and negative gearing proposals).

No other area of policy has more complex interactions and regulations from policy changes than the retirement income field. Complexity is such that legions of financial planners specialise in advice on the interaction of income tax, superannuation, the Age Pension and aged care arrangements.

No other area of policy takes longer lead times (40-plus years) to produce the full effect of policy change, and has the capacity to impose irrecoverable losses in living standards on vulnerable people that they can do nothing to manage or avoid. People, late in their working career or those already retired, are rightly extremely cautious about policy-induced reductions in retirement living standards they have long saved towards. It is easy for political opportunists to exploit that caution.

No review of policy will get to first base if it can be misrepresented by political opponents as creating uncertainty, destroying lifetime saving plans or retirement living standards. Given recent experience, many voters are understandably receptive to a fear campaign of misrepresentation, including those forced to make compulsory savings throughout their working life; those dependent on the full or part Age Pension; wholly or partially self-funded retirees; and indeed all those presently retired, close to retirement, or those who have responded lawfully to legislated incentives to save as previous governments intended. If aroused to uncertainty, these groups can destroy a government.

Many of the changes that would usefully be addressed by a review of retirement income policy are potentially political third rail issues if poorly handled. To take just one example, consider how the family home is treated under the Age Pension asset test and in the structure of Age Pension payments. Think tanks of the left and right alike have recommended that treatment be changed to take more account of wealth in the family home. Without insurance against ‘Mediscare’-type attacks, a potentially important avenue of reform would instantly be used as a scare. Government would have to either instantly rule out any change (compromising the review) or watch the reform exercise die while still suffering the political fallout as ‘the party that wants to tax your home’.

So even sensible proposed changes in policy would be discounted as untrustworthy, disruptive and unlikely to endure without careful protections. No assurance by any political party that “it is not intending to make any change” will be believed for a minute. However, these problems are avoidable with the good management sketched below.

4. Disarm scaremongering by an absolute, up-front guarantee of grandfathering

The simple, tried and proven way to disarm the ‘Mediscare’ tactic and ensure an open, constructive and intelligent Review is to make an upfront, unconditional guarantee: the Review of retirement income will be instructed to avoid any recommendations which would significantly adversely affect anybody who has made lawful savings for retirement, and who is presently retired, or too close to retirement to make offsetting changes to their life savings plans.

That grandfathering guarantee should be absolute and unconditional, referring to the use of similar practices in Australia’s history of superannuation changes from the Asprey report in 1975 through to 2010. The force of any guarantee would be increased if the Government now grandfathered some or all of the 2017 measures initially introduced without grandfathering, in the manner discussed below.

Such unconditional grandfathering would not destroy the retirement income, economic or fiscal benefits of undertaking reform. The very reason that retirement income policy changes take a long time to have their full effect is a good reason for starting policy change early, grandfathering those who made their retirement income savings under earlier rules to ensure implementation of the reforms, and letting the benefits of reform build slowly over time.

5. Propose means to rebuild and preserve confidence and trust in future consideration of retirement income policy changes

Recent policy design efforts have tried to encourage new superannuation products, such as those to address longevity risk. But such effort, necessarily focussed on the distant future of individuals’ retirements, is futile if no one trusts superannuation and Age Pension rule-making any more. If savers cannot trust the Government from 2007 to 2017, or even from February 2016 to May 2016, why should they trust the taxation or regulation of products affecting their retirement living standards 40 years in the future?

To restore the credibility of any changes emerging from the Review, the terms of reference should encourage renewed examination of ideas such as the superannuation charter recommended by the Jeremy Cooper Charter Group, or possible constitutional protection of long term savings and key parameters of the retirement income system.

6. Rebuild credible public, contestable, long-term modelling of the effects of change on retirement incomes

Retirement incomes are the result of complex and slowly developing interrelationships between demographic change, growing community incomes, rising savings, government budget developments, and Age Pension and superannuation policies. Formal, published, long-term modelling of these relationships is an essential tool to understand the impact of demographic change and of policy settings. Formal modelling facilitates public understanding and meaningful consultation, and helps build support for future retirement income reform. Such public modelling was integral to the development of the Simplified Superannuation package in 2006, implemented from 1 July 2007, but was lacking from the 2017 reversal of those reforms.

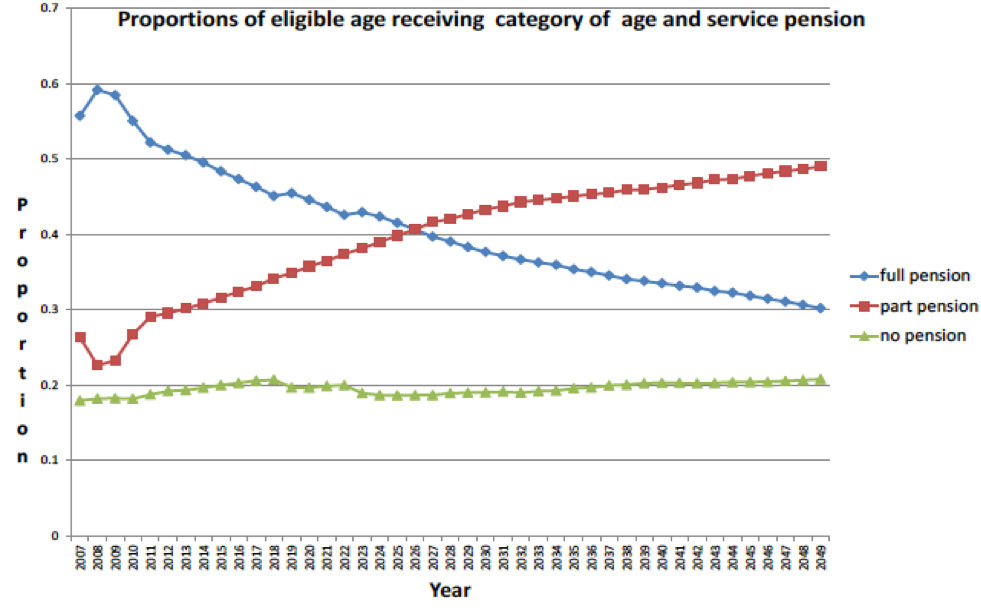

In about 2012, the Commonwealth Treasury stopped publishing long-term modelling in this field with the last of its published forecasts using the RIMGROUP cohort model. The then-projected impacts on the Age Pension through to 2049 from the Super Guarantee measures of 1992 and the Simplified Superannuation reforms of 2007 were for a large decline in uptake of the full Age Pension accelerating from about 2010, but an increase in the uptake of part Age Pensions. There was projected to be only a small rise in the proportion of those age-eligible for the Age Pension who were fully self-funded retirees (Chart One).

The reason that the projected growth in self-funded retirement was slow is instructive: people who would, on pre-2007 policies, have been eligible for a full Age Pension could only slowly build their superannuation savings in response to the 2007 changes. Some of the first cohorts reaching retirement age would have sufficiently larger superannuation savings to be ineligible for the full Age Pension, but would still be eligible for a part Age Pension. Moreover, as they aged and exhausted modest superannuation savings, they would become eligible for a full Age Pension in later life.

Chart One: Treasury’s 2012 projected changes in pension-assisted and self-financed retirement, 2007-2049

Source: Rothman. G. P., Modelling the Sustainability of Australia’s Retirement Income System, July 2012.

The 2017 reversals of the 2007 reforms have never been properly justified. There was no published modelling to suggest costs to the budget were higher than projected, or transition to higher self-funded retirement incomes was slower than projected. As Save Our Super warned at the time, the 1 January 2017 increased taper on the Age Pension asset test created a ‘death zone’ for retirement savings between about $400,000 and $1,050,000 for a couple who owned their home. For every extra dollar saved in that range, an effective marginal tax rate of up to 150 per cent sent the couple backward. (Similar death zones arise for other household types and single persons.)

Superannuation balances at retirement for males of $400,000 or more are common, so the practical burden of the 1 January 2017 perverse de facto tax increase could only be mitigated if a saver could quickly traverse the death zone through utilising high concessional and non-concessional contributions to accelerate late-career super savings. But then the 1 July 2017 reductions in superannuation contribution limits scotched that hope, and compounded the damage of the 1 January 2017 change.

The longer those perverse 2017 incentives are left to operate, the stronger the incentives to build a retirement strategy around limiting superannuation savings and maximising access to a (substantial) part Age Pension. That will negate the objective of the Howard/Costello reforms to defeat adverse demographic budgetary impacts by encouraging rising self-funded retirement, growth in retirement living standards and reduced use of the Age Pension.

Outsiders will probably never know how the policy advice to make the 2017 policy reversal arose, but we speculate that the failure to publish long-term, contestable modelling since 2012 contributed to policies perversely destructive of retirement savings and encouraging tactical exploitation of access to the part Age Pension.

7. Highlight accelerated success in retirement income policy

As a result of the policies that applied up to 2017, we were witnessing a remarkable evolution of Australian retirement income outcomes that is passing unnoticed, because it is poorly explained and reported, and its end-point is still decades in the future. The combined effects of the 1992 Superannuation Guarantee process and 2007’s Simplified Superannuation are beginning to strongly reduce expenditures on the Age Pension much faster than was earlier projected.

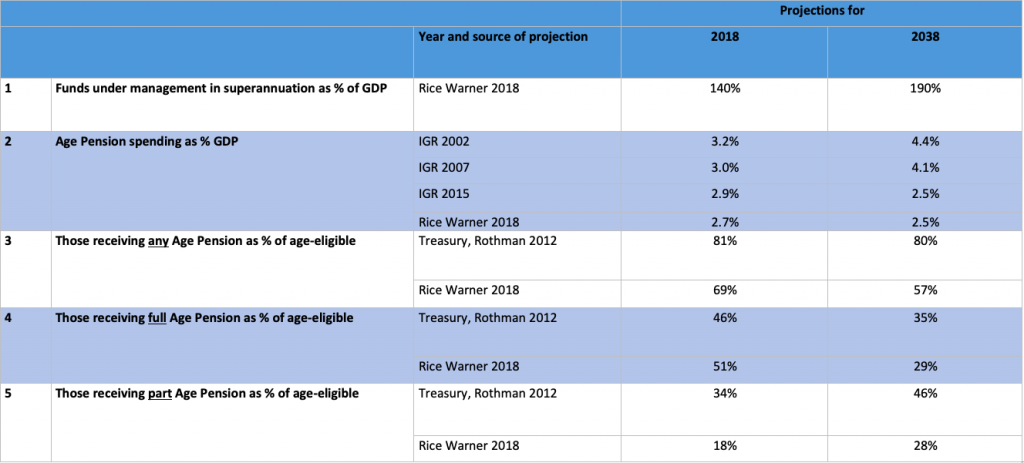

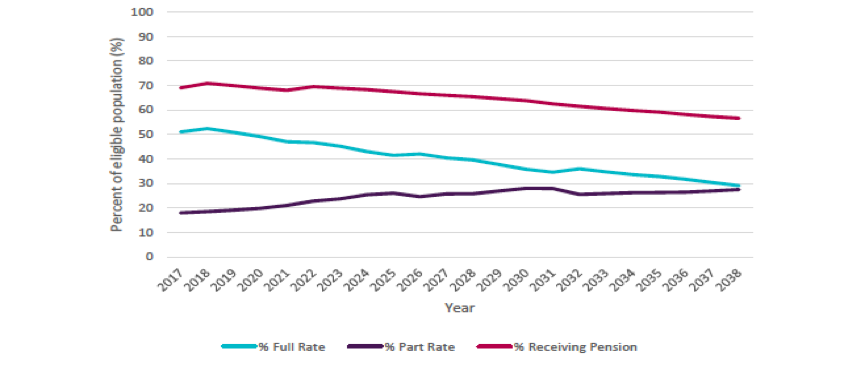

The most recent projections of retirement developments, though only for 20 years out to 2038, were published in 2018 by Michael Rice for Rice Warner actuaries: The Age Pension in the 21st Century. (Treasury had a team leader on secondment to Rice Warner’s team of actuaries for the exercise.) The current trends are remarkable in themselves, but more remarkable in contrast to previous projections of how growing superannuation savings were changing the take-up of the Age Pension only slowly.

The proportion of those age-eligible for the Age Pension who draw a part Age Pension is still rising. (That growth comes from those previously eligible for a full age pension but now partly self-financing their retirement. So there is a net saving to the budget from this trend). But the rise in the take up of the part Age Pension is not as much as earlier projected (Table 1, Panel 5).

What was originally projected to be only a very slight decline in the proportion of the age-eligible receiving any Age Pension (from 81 per cent in 2018 to 80 per cent by 2038), now looks likely to be a very large decline, to about 57 per cent (Table One, Panel 3, and Chart Two).

Table One: Rapid decline in Age Pension uptake projected to 2038

Notes: Intergenerational Report projections quoted are for years closest to 2018 and 2038. 2018 numbers were projections where earlier reports are cited, but are estimates of current data where a 2018 source is cited.

Sources: Intergenerational Reports for 2002, 2007 and 2015; Rothman. G. P., Modelling the Sustainability of Australia’s Retirement Income System, July 2012 (published again in the Cooper Report, A Super Charter: fewer changes, better outcomes, 2013); Rice, M., The Age Pension in the 21st Century, Rice Warner, 2018; Roddan, M., Pension bill falling as super grows, Treasury’s MARIA modelling shows, The Australian, 24 March 2019.

Put the other way around, the proportion of those age-eligible for the Age Pension who are instead totally self-funded retirees will have risen from some 31 per cent in 2018 to about 43 percent in 2038. This is a 12 percentage point rise in those totally self-funding, instead of the earlier projected 1 percentage point rise.

Reflecting this continuing gradual maturation of the system as it stood up to the 2017 policy reversals, spending on the Age Pension has already commenced declining as a share of GDP, instead of rising significantly as had been projected in early Intergenerational Reports. By 2038, spending on the Age Pension will be almost 2 percentage points of GDP lower than originally projected in the first Intergenerational Report in 2002.

Projections will doubtless evolve further. But the remarkable trends noted here are already surprising those working with current expenditure data. The December 2018-19 Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook noted spending on the Age Pension had been overestimated by $900 million for reasons yet to be fully understood. The shortfall seems likely to involve the trends noted here, among other factors.

Chart Two: 2018 Projected proportions of the eligible population receiving the Age Pension, by rate of Age Pension

Source: Michael Rice, The Age Pension in the 21st Century, Rice Warner, p 31.

To most, the evidence of rising living standards in retirement, more self-funding through lifetime savings, less reliance on the Age Pension, a falling share of Age Pension spending in GDP and the disarming of the demographic and fiscal time bombs identified in earlier Intergenerational Reports would look like a policy triumph.

Further to this private sector modelling, in December 2018, an FOI request led to the first fragmentary public evidence of the initial uses of a new Treasury microsimulation model, MARIA , a “Model of Australian Retirement Incomes and Assets”. The model uses advances in data and computing power since Treasury’s 1990s RIMGROUP model was built to move from cohort modelling of age and income groups to microsimulation modelling of the population. This first report indicated Age Pension dependency falling markedly. Subsequent reporting of FOI information in March 2019 adds to public information that spending on the Age Pension is now falling towards 2.5% of GDP by 2038, a remarkable 1.6 per cent of GDP lower than was projected in the Intergenerational Report of 2007, the year the Costello Simplified Super reforms were enacted.

To give a sense of scale, 1.6 per cent of 2018 GDP is about $29 billion dollars. Even if GDP grew by 1% a year to 2038 (which would be a lamentable shrinkage in per capita GDP), spending on the Age Pension would be by then about $36 billion a year lower than previously projected, apparently wholly as a result of more people saving more in superannuation than was projected in the Intergenerational Report of 2007.

On 24 June 2019, more evidence of superannuation policy success became available. Analysis by Challenger, Super is delivering for those about to retire, noted that the average newly retired Australian is not accessing the Age Pension at all. Only 45% of 66-year-olds were accessing the Age Pension at December 2018 and only 25% of them were drawing a full Age Pension. Of course, many of those might fall back on the Age Pension in later life when they exhaust their superannuation capital. Thus, if retirees are to remain wholly self-funded during their whole retirement, superannuation balances at retirement will need to keep rising. Other things being equal, 2017’s imposition of a $1.6 million cap and tax at 15% on amounts above that balance reduce the time that retirees can remain independent of the Age Pension.

Every additional person who wholly self-funds their retirement is, prima facie, achieving a better retirement living standard than they could have enjoyed by arranging their affairs to access only the Age Pension and to send the bill to working age taxpayers. This is not merely a budget success. An economy in which individuals save for retirement, contributing funds and real resources for reallocation through the financial sector to fund investments will be much more dynamic and efficient than one more dependent on the Age Pension, in which people pay incentive-deadening taxes for redistribution through the welfare system.

It is bewildering to us that the accelerated success of superannuation policy, which has helped people save for their desired retirement standard of living, is not being trumpeted from the rooftops. Instead, the facts are dribbling out without explanation and context from FOI applications. Those facts are lost against the backdrop of incessant criticism from some commentators of More than enough saving and excessive revenue forgone from the tax treatment of superannuation.

It is vital for protecting the Government from a repeat of the backward steps on retirement income policy in 2017, for restoring the legacy of the Howard-Costello reforms and for timely identification of sustainable future reforms, to re-establish regular published, contestable and peer reviewed modelling of how retirement income policy is working.

8. Commission initial modelling of three scenarios

We suggest Treasury should use MARIA to model three scenarios over a long-term time frame such as 2000 to 2060 to clarify the starting point for the Review of Retirement Income Policy.

Rather than study retirement income policy solely as a Commonwealth budget issue of the revenue hypothetically forgone in tax incentives for superannuation and the expenditure on the Age Pension, the modelling needs to be set in the fuller context of the Howard Government’s 2006-2007 analysis of Simplified Superannuation. Its output ought to include impacts on retirement incomes, the ‘RI’ in MARIA, not just on the budget.

As noted above, the overarching objective of policy ought be to enable higher lifetime saving and rising living standards in retirement for those in a position to save for self-funded retirement, while preserving the Age Pension as a safety net for those unable to save for a better retirement living standard. Modelling should project implications for average self-financed and Age Pension retirement incomes under each scenario, as well as for government revenues and expenditures.

a) A baseline scenario

We suggest the first scenario for long-term modelling should be the projected effects by 2060 of the continuation of Age Pension and superannuation policies as at end 2016. That would be comparable against the earlier 2012 Treasury modelling, and would show the impact of another 6 to 7 years’ data on the maturation of the Super Guarantee (including scheduled future increases) and the Simplified Superannuation reforms of 2007.

b) A current policy scenario

We suggest a second useful scenario would be to model the current policies. When the current policy scenario is compared to the baseline scenario, that would give an indication of the effect of the change in the taper rate of the Age Pension asset test, the imposition in the retirement phase of a 15% tax on earnings on superannuation balances above $1.6 million, and tighter restrictions on concessional and non-concessional contributions. Effects on individual retirement incomes, as well as comparisons of effectson government revenue and expenditure over time, should be made between the two models.

It might be objected that the behavioural responses to the 2017 changes are too recent to have shown up in data and thus too difficult to model. But to assert that we can have no estimate of the likely effect of those policy changes on retirement incomes would be in effect to concede that they should never have been proposed or implemented.

c) Future policy change scenarios

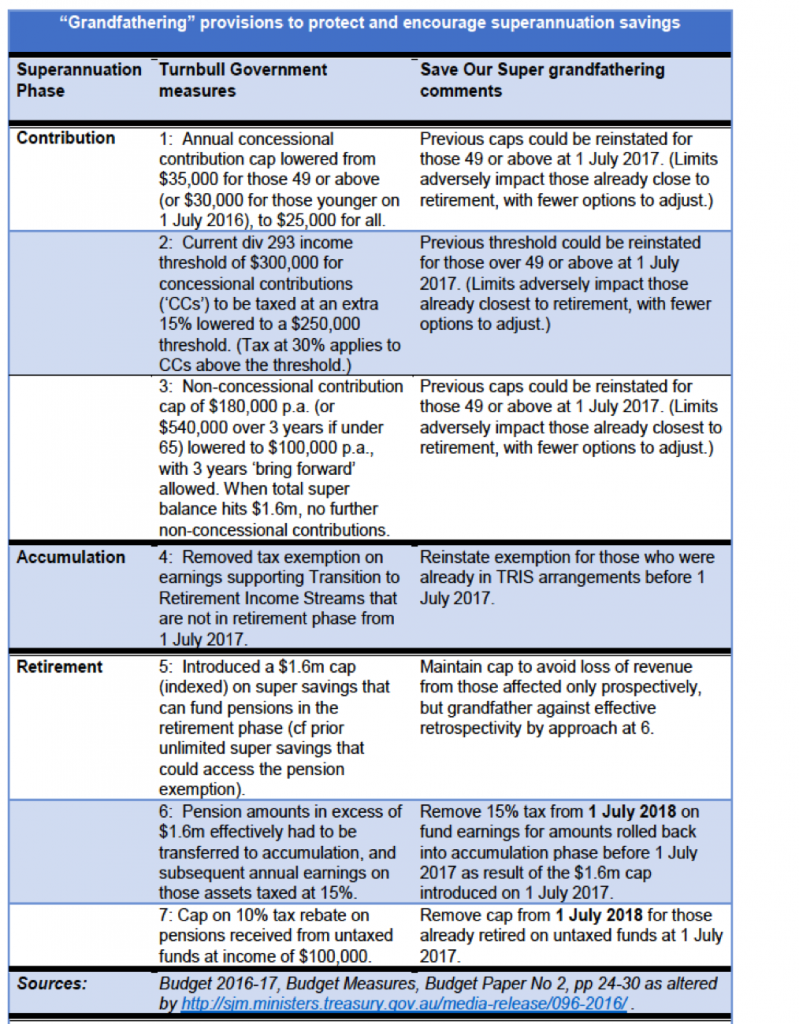

A third useful scenario could involve empirically testing policy changes the Government wanted to explore, including grandfathering the changes introduced in 2017 and summarised in Table Two.

Any mix of measures selected should cohere around the Government’s retirement income strategy, to allow those who can save to raise their retirement living standards, to protect the efficacy and affordability of the Age Pension as a safety net for those who cannot, and to ensure as many as possible are in the first group. The selection of measures must rest on the evidence of public, contestable, long-term modelling of outcomes on both retirement living standards and the government budget.

Because of these strategic and empirical imperatives, Save Our Super advocates that the grandfathering of all the measures of Table Two be enumerated and modelled, as well as the 2017 change to the means testing of the Age Pension and the impact of Superannuation Guarantee changes.

Table Two: Options for grandfathering 2017 superannuation changes

We illustrate one possible, strategically coherent path forward but without any implied prioritisation. Some potentially useful measures might:

- Reduce the burden of the Superannuation Guarantee on the youngest (who have longest to fund their own preferred retirement living standards and face the highest competing demands on their early-career budgets) and the poorest (who will in any event accumulate insufficient savings over their working lifetimes to become ineligible for the Age Pension). This could involve either raising the cut-in point for the Superannuation Guarantee, halting its programmed rate increases, or both.

- Against the merits of the Superannuation Guarantee must be set the cost that it forces a constant rate of saving for employees by their employers over the employees’ working lifetimes. In any event (but especially if the Government raises the Superannuation Guarantee rate), this is a particular burden on the young, those in tertiary study, those seeking to buy their first home, those establishing a family and those with low or punctuated career earnings.

- One curious and little noted feature of the Superannuation Guarantee is that (broadly speaking) it applies to any employee over 18 who earns $450 gross or more a month. This extraordinarily low threshold has not been altered since the Super Guarantee was introduced at 3 per cent in 1992 – over a quarter of a century ago. At that time, the monthly $450 trigger corresponded to the then annual tax-free threshold in the income tax of $5,400. With the Superannuation Guarantee now at 9.5 per cent and scheduled to increase to 12 per cent, it is now a significant impost that falls as forgone wages on young and/or poor workers, when they have priorities of education, housing and family expenses much more pressing than commencing saving for retirement more than 40 years in the future. If the Superannuation Guarantee cut in at the monthly gross earnings equivalent to the current tax-free threshold, the trigger would now be $1517 a month, not $450 a month.

- Remove the discouragement of saving from effective marginal tax rates of over 100%, encouraging saving by those who can save to escape reliance on the full Age Pension. This would require reversing the increased taper on the Age Pension asset test imposed on 1 January 2017 and reinstating the Costello reform of 2007.

- Allow those who are able to save for their desired retirement standard of living, in the latter parts of their career, access to higher concessional and non-concessional superannuation contributionlimits, as shown in Table Two.

- Acknowledge that self-funding a retirement standard of living which is higher than the Age Pension requires a large capital sum at retirement – the Age Pension for a married couple is estimated to have an actuarial value of over $1 million, with the costs rising in an environment of near-zero interest rates. At present, all political parties say they want an end (increased self-funding of retirement), but seem to attack the means to that end: a large capital sum accumulated at the end of the saver’s working career. With the continuing drift of interest rates towards zero, whatever unexplained calculations arrived in 2016 at the $1.6 million cap on superannuation should be re-examined, with a view to grandfathering the cap as shown in Table Two, raising it or abolishing it. The interest earnings from a $1.6 million sum is now almost 40% lower than it was in early 2016. Abolishing the $1.6 million cap would re-capture many of the simplification benefits of the 2007 Simplified Super reforms, which were destroyed by the 2017 changes.

d) Strategic direction of future policy change scenario

These four classes of change have clear strategic directions: they are pro-choice, pro-personal responsibility and support rising living standards in retirement. They reduce emphasis on forced savings at a high and constant rate over the whole of working life from the earliest age and the lowest of incomes. They increase emphasis on saving at the rate chosen by individuals over their working careers in the light of their circumstances. The shift would likely result in faster late career savings after educational, family formation and mortgage commitments have been met. The shift would be pro-equity, in that it would avoid reducing the living standards of the youngest and poorest in the workforce, without ever helping many of them achieve retirement income living standards above the Age Pension. And it would reduce the constituency of voters denied growth in their own disposable incomes and supportive instead of increased government transfers to them for their early-career expenditures (such as childcare and other family benefits).

e) Budget effects of future policy change scenario

Of these four classes of change, the Superannuation Guarantee changes would raise significant revenue for the government budget, since higher incomes paid as wages would be taxed under normal income tax provisions, rather than at the lower rate for superannuation contributions. The other three measures would have a gross cost to budget revenue relative to the current measures, but would continue and likely accelerate the recent and faster-than-projected exit of retirees from dependence on the full Age Pension. That will save some future budget outlays, and it is unclear until public, contestable long-term modelling is published what the net effect on the budget would be, and its time frame.

Recall, however, that the origins of this debate were the demographic time-bomb facing Australia, and the intrinsically long-term challenge of building life-time savings for long-lived retirement. A measure that ‘breaks into the black’ even decades hence might be counted a success.

f) Retirement income effects of future policy change scenario

Whatever the net budget effects and their timing, it is clear a package such as sketched in scenario 3 will raise Australian’s retirement incomes and protect the sustainability of the Age Pension

9. Let the modelling speak

Only long-term modelling can show which measures are likely to have the best pay-offs in greatest retirement income improvements at least budget cost. Choice of which measures to develop further are matters for judgement, balancing the possible downside that extensive policy change outside a superannuation charter may only further damage trust in retirement income policy setting and in Government credibility.

*******************************************************

Reversionary pension v BDBN: which one wins?

By Bryce Figot, Special Counsel, DBA Lawyers and Daniel Butler, Director

There is a misconception that reversionary pension documentation will always apply before a binding death benefit nomination. If the SMSF deed is silent on the question, it can be entirely possible at times that the binding death benefit nomination (‘BDBN’) will apply before any reversion pension documentation.

The reasoning is to do with several often overlooked laws. This article aims to address some of these laws, as well as offer a practical solution.

If the SMSF deed provides that reversionary pension documentation overrides any BDBN, that may well be the case for that particular SMSF. However, that might not be in anyone’s best interests, and could result in significant liability for advisers.

The relevant law

Ultimately, what matters is what a judge thinks.

An analogous Queensland decision from 2007 provides insights. In Dagenmont Pty Ltd v Lugton [2007] QSC 272 the trustee of a discretionary trust executed an instrument stating that it would pay a person an amount of $150,000 annually. The validity of this was challenged.

Chesterman J summarised the law behind the challenge as follows:

According to the Law of Trusts by Underhill and Hayton 16th edition (p 690):

… it is trite law that trustees cannot fetter the future exercise of powers vested in trustees ex officio … Any fetter is of no effect. Trustees need to be properly informed of all relevant matters at the time they come to exercise their relevant power.

Meagher and Gummow in Jacobs Law of Trusts in Australia 6th edition para 1616 say:

Trustees must exercise powers according to circumstances as they exist at the time. They must not anticipate the arrival of the proper period by … undertaking beforehand as to the mode in which the power will be exercised in futuro.

Professor Finn (as his Honour then was) in his work Fiduciary Obligations wrote (at para 51):

Equity’s rule is that a fiduciary cannot effectively bind himself as to the manner in which he will exercise a discretion in the future. He cannot by some antecedent resolution, or by contract with … a third party – or a beneficiary – impose a “fetter” on his discretions.

Finkelstein J summarised the position succinctly in Fitzwood Pty Ltd v Unique Goal Pty Ltd (in liquidation) [2001] FCA 1628 (para 121). His Honour said:

Speaking generally, a trustee is not entitled to fetter the exercise of discretionary power (for example a power of sale) in advance: Thacker v Key (1869) LR 8 Eq 408; In Re Vestey’s Settlement (1951) ChD 209. If the trustee makes a resolution to that effect, it will be unenforceable, and if the trustee enters into an agreement to that effect, the agreement will not be enforced (Moore v Clench (1875) 1 ChD 447), though the trustee may be liable in damages for breach of contract …

Also, judges often consult from leading texts such as legal encyclopaedias. Two legal encyclopaedias often consulted by judges are Halsbury’s Laws of Australia and The Laws of Australia.

Firstly, Halsbury’s Laws of Australia states at [430-4185]:

A trustee must not permit others, especially the beneficiaries, to dictate the manner in which his or her fiduciary discretion ought be exercised. For this reason, a trustee must not bind himself or herself to a future exercise of the trust in a prescribed manner which is determined by considerations other than his or her own conscientious judgment at that future time regarding what is in the beneficiaries’ best interests

Similarly, The Laws of Australia states at [15.14.1590]:

Trustees must not permit others, especially the beneficiaries, to dictate to them the manner in which the fiduciary discretion ought be exercised. Trustees must not bind themselves contractually to exercise a trust in a prescribed manner, to be decided by considerations other than their own conscientious judgment at the time, regarding what is in the best interests of the beneficiaries. [2] For example, in Re Stephenson’s Settled Estates(1906) 6 SR (NSW) 420; 23 WN (NSW) 153, Street J held that it was a breach of trust for trustees with a power of sale to enter into a contract binding them to sell trust property for a fixed price at a specified future date.

In other words, if an SMSF deed gives a trustee a discretion (eg, what to do with a member’s death benefits when the member ultimately dies), the trustee must not decide today how it will exercise that discretion in the future. If the trustee does decide today how it will exercise its discretion in the future, that decision will be unenforceable.

Naturally, it is possible for an SMSF trust deed to alter the above ‘default’ position and to instead allow a trustee’s discretion to be bound. (Incidentally, that was exactly what happened in Dagenmont and why the challenge in that case failed.)

Most SMSF deeds drafted in the last 20 years have provisions allowing a member to bind a trustee’s future discretion pursuant to a BDBN. However, there is a lot more variability and vagaries as to what SMSF deeds might provide regarding reversionary pensions.

What if the SMSF deed provides pension documentation overrides any BDBN?

As noted above, if a specific SMSF’s deed provides that pension documentation overrides any BDBN, that might well be the case for that specific SMSF. However, we ask whether such a provision is in anyone’s best interests.

Consider the following situation. You are an accountant with a limited AFSL. Your client has made a BDBN in favour of her estate. Your client tells you that upon her death:

- she wants her pension to revert to her husband; and

- she wants her accumulation interest to be paid to her estate (ie, legal personal representative).

You prepare pension documentation stating that her pension reverts to her husband.

Your client dies.

The client’s executor states that had the deceased been fully aware of all relevant information and of all of her legal rights and obligations, she would not have signed the pension documentation. You now face two unenviable options. You can either:

Unenviable option 1 (you have committed a crime): say that you DID advise the deceased of all relevant information and all of her legal rights and obligations and then drafted the pension documentation. If so you have almost certainly engaged in legal practice. In Victoria, it is an offence punishable by, among other things, up to two years in prison for someone who is not an Australian legal practitioner to engage in legal practice (Legal Profession Uniform Law Application Act 2014 (Vic) sch 1 s 10(1)). Similar punishments apply in all other jurisdictions.

Unenviable option 2 (you are negligent): say that you did NOT advise the deceased of all relevant information and all of her legal rights and obligations but you nevertheless drafted the pension documentation. If so you might well have breached your duty of care owed not just to the deceased, but also to the deceased’s dependants, executor and any beneficiaries of the deceased estate (see Hill v Van Erp (1997) 188 CLR 159). You may be liable to them under (among other things) the tort of negligence for any loss, damages and costs suffered.

The practical solution

It is critical to be very aware of the limitations of what a non-lawyer can do.

Consider a client who wants a ‘simple’ BDBN or a ‘simple’ pension reversion. With a proper product disclosure statement, disclaimers, warnings and file notes, it may well be possible for you as a non-lawyer to:

- determine whether your client is giving you properly informed instructions; and

- act as a ‘mere scribe’ and populate a template.

However, even then you would be well advised to recommend the client have these documents settled by their estate planning lawyer. The moment things become more complex, it is extremely risky to proceed without a lawyer providing the ultimate advice and the ultimate ‘sign off’ in respect of the pension documentation and the BDBN.

If you are a non-lawyer and you are involved in documentation attempting to direct that, for example, some pension is paid one way upon death (eg, to a spouse) and accumulation benefits are paid another way (eg, to an estate) you should adopt the absolute highest level of caution. You should be extremely reluctant for the ‘buck to stop’ with you or your firm. To properly implement this situation almost certainly constitutes engaging in legal practice and it should a lawyer who bears the final risk (if for no other reason, the lawyer — unlike you — will be covered by appropriate insurance for legal work).

Your firm’s procedures and quality control notes should reflect this.

Why it can be strategic for the SMSF deed to provide that a BDBN overrides pension documentation

There can be significant advantages in having an SMSF deed that expressly states that a BDBN overrides inconsistent pension documentation. We have already written about this in previous articles and no doubt we will write about this again in future articles.

Conclusion

It is incorrect to believe that pension reversion documentation will always override BDBNs.

Ultimately though the SMSF deed will play a very important role. However, an SMSF deed that provides that pension documentation will override a BDBN can cause a non-lawyer to bear significant legal risks.

Other relevant articles

Other recent relevant articles include https://www.dbalawyers.com.au/ato/reconciling-inconsistencies-between-reversionary-pension-nominations-and-bdbns/ and https://www.dbalawyers.com.au/ato/reversionary-pension-vs-bdbn-which-outcome-is-preferred/

* * *

This article is for general information only and should not be relied upon without first seeking advice from an appropriately qualified professional.

Note: DBA Lawyers hold SMSF CPD training at venues all around Australia and online. For more details or to register, visit www.dbanetwork.com.au or call Marie on 03 9092 9400.

13 August 2019

Super industry riches on hold after Labor poll loss

The Australian

3 August 2019

Judith Sloan – Contributing Economics Editor

The election result was a major disappointment to the vast majority of players in the superannuation industry. A Labor government would have ushered in a veritable purple patch, for the industry super funds in particular.

There would have been no debate about whether or not the Superannuation Guarantee Charge would be lifted from 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent. Indeed, there was a possibility that Chris Bowen, as treasurer, might have brought forward the increase in the contribution rate. According to legislation, the SGC will increase to 10 per cent from July 1, 2021, and reach 12 per cent in 2025.

All that pesky discussion of removing industry super funds from the default lists in modern awards would have faded away. And there would have been no talk of removing the monopoly position of industry super funds in key enterprise agreements.

The whole idea of the selection of 10 “best in show” default funds for new workers would have been quickly forgotten. And anyone who even mentioned the potential role for the Future Fund as a manager of superannuation funds would have been quickly dismissed.

To be sure, some lip service would have been paid to reducing the magnitude of fees and charges imposed by funds. And there might have been some feeble efforts to deal with the problem of multiple accounts and unwanted and/or unusable life insurance.

But bear in mind nothing would have been done to upset the industry super funds or the freeloading insurance companies. There would have been no discussion of moving away from opt-out insurance, for instance.

But those dreams of guaranteed riches and expansion have largely evaporated for the industry, and the players must deal with a government that is far less committed to the whole notion of compulsory super than Labor. It is now hand-to-hand combat as the industry seeks to defend its current privileges, as well as truly lock in the rise in the SGC.

The appointment of senator Jane Hume as Assistant Minister for Superannuation, Financial Services and Financial Technology has also sent shivers down the spines of the well-remunerated folk in the super industry. Not only is she whip-smart but she also has direct professional experience in the industry, including a stint at AustralianSuper, the largest industry super fund.

There are many issues to sort out above and beyond what should happen to the SGC. Some of them were canvassed in work undertaken by the Productivity Commission, as well as in other reports, including ironically the Cooper review that was commissioned by the Labor government and released in 2010.

A large slate of bills to reform various aspects of super was developed by the Coalition in its last term in office. But the combination of the composition of the Senate and the unrelenting opposition by the super funds, the trade unions and Labor meant most of these bills were never even presented to the upper house.

Mind you, future threats by superannuation lobbyists of electoral retaliation for unco-operative crossbench senators may well have lost their impact.

The issues the government must deal with during the coming term include: the governance of super funds, strengthening the regulation of super, the elimination of multiple accounts, the establishment of single default accounts that will follow members as they change jobs, the fate of poorly performing funds and fund mergers, and whether insurance should become a fully opt-in arrangement.

For all the carry-on about our system of compulsory super being the envy of the world — read: the envy of fund managers around the world — there are multiple problems with the system, including the often perverse interactions with other components of our retirement incomes system. These will be the likely focus of the upcoming Productivity Commission review into retirement incomes.

It’s not clear where the government will direct its efforts in terms of improving the efficiency of the super system and improving the accountability of the funds. Earlier this year, a small step was achieved when a law was passed that means that inactive — defined as those for which there has been no contribution for 16 months — accounts with balances of less than $6000 will be shifted to the Australian Taxation Office, oftentimes to be merged with another account held by the member.

The effect of this change is that unwanted insurance premiums will no longer be unwittingly deducted from these accounts and their value can be preserved. A further change is in the wind that will convert insurance to an opt-in arrangement for all new members younger than 25 and for members with accounts of less than $6000.

Even these small modifications have attracted the ire of some of the super lobbyists, who allege that members will unknowingly lose the value of insurance. They cite figures about the number of under 25-year-olds with dependants — it’s 10 per cent — as well as the proportion with mortgage debts. They predict that insurance premiums will rise because younger members will no longer be forced to cross-subsidise older ones.

The key problem of multiple accounts remains unresolved at this stage. The Productivity Commission says about a third of super accounts — 10 million in total — are unintended multiple accounts. This results in the loss of $2.6 billion per annum in pointless fees, charges and insurance premiums. The government needs to act on the recommendation of the Hayne banking royal commission that each person should have only one default super account and that there must be a mechanism to “staple” a person to this single default account. Again, the industry is pushing back on this proposal.

One of the more ludicrous proposals doing the rounds is that members’ super benefits should automatically transfer each time a worker changes a job unless the worker nominates otherwise. This is surely no one’s idea of a stapled product, with workers potentially changing funds every time they change jobs.