Author's posts

Coronavirus: Perks and loopholes can’t endure as we run up debt

The Australian

30 March 2020

Adam Creighton

The young and poor have little say in society but they are incurring the bulk of the costs from the shutdown.

Whether it’s their incomes, their schooling or their ability to enjoy life, the sacrifices that students and so-called generations X and Y are making for the over-75s are very significant. Unlike the Spanish flu 90 years ago, it seems coronavirus is of little threat to the vast majority.

The $320bn the government and Reserve Bank have allocated so far to staunch the self-imposed economic carnage will have to be paid for. The plunge in tax revenues could well be as significant as the increase in outlays, leaving a gap that will test governments’ ability to borrow. There’s already $400 trillion of debt sloshing around the world.

And the bill will come long after those whom the younger generations have tried to protect have died. It’s reasonable to give some thought now to how the costs will be shared.

Policies that were thought fair and reasonable only months ago will start to look unfair, even absurd. The government will face stark choices about how to allocate the burden. Will it crush the productive sector of the economy with even more income tax?

Everyone will suffer in degrees during this crisis, but it’s only fair that those who are being saved, especially if they are financially equipped, pay a disproportionate burden of the cost.

(It’s true retirees have seen huge falls in their superannuation balances, but once a vaccine is found in a year or two, their accounts are likely to roar back to life.)

The Commonwealth Seniors Health Card, which is a benefit for retirees who are too well-off to quality for the Age Pension, should be immediately dumped.

How can we have people queuing up for soup in Sydney’s Martin Place (as was the case on Sunday night), while taxpayers fork out hundreds of millions of dollars a year to ensure cheap medicines and transport for those who can easily afford them anyway?

Scrapping the seniors and pensions tax offset, which provides a tax-free threshold of about $33,000 for over-65s and about $58,000 for couples, is also a no-brainer. Naturally, these two changes will cause some discomfort for those affected, but nothing compared with the chaos recently foisted on millions.

It’s obvious the superannuation guarantee should be suspended for the rest of the year, as I’ve argued repeatedly. The government is forgoing almost $20bn a year in tax by keeping it when it needs the revenue urgently.

Coronavirus: Economic bailouts

| Country | Bailout amount | Additions |

|---|---|---|

| USA | $A3.2 trillion | + $A810bn for layoffs |

| Germany | $A1.3 trillion | + $A89bn for layoffs |

| UK | $A627bn | + 80% of salaries up to $2390/month for layoffs |

| Japan | $A437bn | + cash payments and travel subsidies for layoffs |

| Australia | $320bn | + workers and sole traders can access $10,000 tax free from superannuation, + $1500 per fortnight for workers |

| Canada | $A121bn | + $2000/month for 4 months for layoffs |

| South Korea | $A66bn | |

| Norway | $A15.2bn | + 100% of salary for 20 days / 80% if self-employed for layoffs |

| New Zealand | $A11.5bn | + wages covered for people who need to self-isolate |

As of March 31, 2020

Rather than taxing younger generations or workers to oblivion, it’s best to curtail generous arrangements, at least temporarily. These tax increase would have relatively little or no impact on disposable incomes; indeed, in the case of suspending the super guarantee, take-home pay would increase for millions of workers.

Other options might include a significant inheritance tax imposed, say, for the next 20 years to help defray the gargantuan tax burden that has just been put on everyone who is not going to die in that period.

Tax-free earnings on superannuation in the retirement phase should cease, at least temporarily. Currently, the earnings of superannuation funds for retirees face zero taxation.

Everyone else pays 15 per cent tax. It should be the same for everyone (as the Henry tax review recommended, by the way). Fifteen per cent is still a lot more generous than marginal income tax rates.

Cancelling the refundability of franking credits — for everyone, not just self-funded retirees — is another option.

To be sure, this would cause real pain, given some retirees quite reasonably have structured their affairs around them. But this is a crisis.

There are some economic bright sides for younger people. If a house price crash eventuates, those with jobs and to obtain credit will be more easily able to afford a home.

Whether house prices fall for long remains to be seen, though. In times of uncertainty, gold and property tend to be relatively attractive assets and immune from inflation.

And significant inflation may well be on the horizon. The borrowing lobby in society is much more politically powerful than the lending lobby. That is, the constituency that benefits from inflation (anyone with debt) is greater than those who wouldn’t.

What’s more, a niche group of economists reckons the central bank can give us all money directly — say, $10,000 each straight into our bank accounts — without undermining the economic system.

It’s known as Modern Monetary Theory and, understandably, it is becoming popular.

“There’s no such thing as a free lunch” was branded into me through years of economics study. It’s hard to imagine that we can just make new money out of thin air without serious long-term costs to the economic system, or certainly respect for it.

Why would anyone bother working or saving?

The fiscal situation is looking so dire a future government might well give MMT a try. It’s so seductive. They should be wary, though. A great inflation has unpredictable consequences, which history suggests can be terrible.

Nevertheless, if inflation does break out, the burden of the economic shutdown would play out very differently. It would remove the government and private debt burden, obviating the need for the various tax increases suggested above. Anyone with significant cash or deposit holdings would be wiped out.

For now, however, this is all academic.

As in an ordinary war, the young are doing the heavy lifting and face a massive tax burden. It could be a bit less burdensome if reasonable, temporary tax increases were imposed for the over-65s to help defray the costs.

It’s important to keep perspective. Roughly 165,000 people die in Australia each year; about 3000 from influenza.

Meanwhile, the economy is being destroyed — real and permanent damage — for uncertain benefit.

If we totally shut down the economy, as many are advocating, when does it reopen? And if it reopens and the virus emerges again, is it shut down once more?

It’s patently not possible to keep turning an economy on and off every few months without destroying civilisation.

Treasury to analyse if taking compulsory super guarantee to 12pc will hurt wages

The Australian

5 March 2020

Michael Roddan

The Morrison government has commissioned the Australian National University to analyse whether wages will be harmed if the scheduled increase in the superannuation guarantee to 12 per cent is allowed to go ahead.

Appearing before a Senate Estimates committee on Thursday, Robb Preston, the manager of Treasury’s retirement income policy division, revealed the government’s key economic department had contracted a number of independent economic researchers to provide analysis of the superannuation system for Scott Morrison’s retirement income review.

Mr Preston said the ANU’s tax and transfer policy institute, a well-respected policy research unit headed by Professor Robert Breunig, would be providing Treasury with modelling of the relationship between wages and the superannuation guarantee (SG).

The SG is legislated to rise from 9.5 to 12 per cent by 2024, but critics have warned that forcing workers to carve off more savings into nest eggs will cull wages growth, cost the federal budget billions in foregone revenue thanks to generous super tax concessions, and mainly benefit wealthy retirees.

Mr Preston said modelling of how changes in the superannuation guarantee affected rates of voluntary saving would be provided by Monash University, while Curtin University would be examining how the superannuation system affected pre-retirement behaviour.

Actuarial firm Rice Warner will also be providing Treasury with “long-run” modelling estimates of the retirement income system.READ MORE:Workers ‘pay for increases in super’|Stay calm: super giants|Higher super to ‘benefit the wealthiest retirees’

“The panel is very interested in understanding the trends affecting the retirement income system going forward,” Mr Preston said.

“We’re endeavouring to take a very comprehensive approach to our work,” he said.

“We’re planning to release a report to government by 30 June,” he said. Australian Taxation Office deputy commissioner James O’Halloran on Thursday said the government revenue agency disqualified some 300 self-managed superannuation fund trustees every year, noting there were a small number of funds engaged in “tax mischief”.

“In terms of criminality, there are instances perhaps where a SMSF might be carrying out the avoidance or minimisation of tax,” Mr O’Halloran told Estimates.

Labor, the ACTU and the $700bn industry fund sector have argued for the higher rate.

The independent Grattan Institute has come under criticism from the super sector after it argued raising the super guarantee to 12 per cent would cost the budget $2bn a year in tax concessions, hurt low-income workers and fail to drive a meaningful increase in retirement income or result in a lower age pension bill.

Confidential Treasury modelling of the super system, obtained under Freedom of Information laws and reported by The Australian last year, is “broadly consistent” with the Grattan Institute ’s findings.

According to the documents, Treasury also warned increasing the super guarantee rate would cost workers wage rises and would exacerbate the gender income gap, a position also recently argued by the Australian Council of Social Service.

The Age Pension is the biggest government expenditure at nearly $50bn a year . In 2002 it cost 2.9 per cent of GDP and is tipped to hit 4.6 per cent by 2042.

Consequences of increasing the superannuation guarantee rate

12 March 2020

Jim Bonham

1 Introduction

Between now and 2025 the compulsory “superannuation guarantee” (SG) contribution to superannuation is legislated to increase in steps from 9.5% of gross income to 12%.

This move is being opposed by some people, particularly the Grattan Institute (see https://grattan.edu.au/report/money-in-retirement), amplified by op-eds in the press.

Unfortunately, formal “think tank” and academic reports tend to be inaccessible to the average reader. Calculations may be opaque; and journalists often manage to make the impending increase look quite complicated and confusing.

It does not have to be so. This short note explores the immediate consequences of the legislated increase in the SG rate from 9.5% to 12% and introduces an alternative proposal to increase the SG rate to 10%, or even leave it unchanged, and drop the contribution tax entirely.

Click here to download PDF version

2 The issues

The table below lists what I perceive to be the main points of concern, and a brief comment on each. This is provided for context, not as a detailed commentary on any specific position.

| Perceived problem | Comment | |

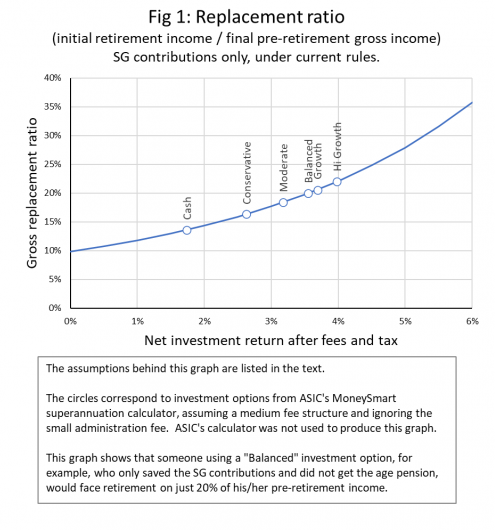

| (a) | Retirees already have enough money so there is no need to beef up super. | Depending on investment returns, current SG contributions will only provide an initial retirement income of 14% to 25%, or so, of final employment income (depending on investment choices). |

| (b) | Increasing the SG rate will depress incomes. | The government has reportedly asked ANU to advise specifically on this issue. Gross incomes will fall by 2.23% (given assumptions detailed in the text), but there is an alternative. |

| (c) | Increasing retirees’ assets will disproportionately reduce their age pension entitlement | This reflects a problem with the structure of the age pension, not super. In any event it will take a decade or so to become significant, leaving plenty of time to fix the structural issue. |

| (d) | The budget can’t afford the cost | The cost to the government of the planned increases, per employee, is equivalent to about 0.5% of their gross income – the equivalent of a modest tax cut. |

Each of these issues is discussed in more detail below. The intention is not to provide detailed rebuttals of any specific point of view, but rather to add context to the upcoming increase, and to suggest an alternative approach.

3 How much does the SG provide?

It can be a daunting task to work out how much superannuation one will have in retirement, what its real value will be and how that might relate to one’s income needs.

Fortunately, help is available from on-line calculators such as the excellent one provided by ASIC (https://moneysmart.gov.au/how-super-works/superannuation-calculator) which also provides detailed actuarially determined estimates of long term investment returns, fees and earnings for several common investment styles, as well as estimates of inflation and wages growth (as reflected in rising living standards).

A common measure, used by the OECD for example, for assessing retirement funding systems is the replacement ratio, which is the initial income in retirement divided by the final employment income. (Obviously, this only makes sense for someone who remains in steady employment up to retirement and doesn’t apply to those with a more fractured employment history).

It is generally accepted that a replacement ratio of 70% represents good practice and, in the absence of better information, it seems to “feel” about right.

Fig 1 shows the replacement ratio expected just from current SG contributions and their compounded investment returns, assuming

- SG rate is 9.5%, taxed at 15%

- Wages growth is 3.2%

- Length of employment is 45 years

- On retirement, superannuation is converted to an allocated pension from which 5% per annum is drawn as income in the early years.

- Complications such as contribution caps are ignored.

The simple conclusion from Fig 1 is that, however the superannuation account is invested, the SG contributions alone will not provide anything like a 70% replacement ratio.

Most people will need to supplement their SG contributions substantially with further voluntary superannuation contributions, the age pension, or other investments outside superannuation, in order to live at a level anything like what they were used to.

There is thus a lot of scope to increase the SG contributions, which goes a long way toward refuting Issue 2(a).

4 How will the SG rate increase affect pre-retirement incomes?

To keep things simple, we’ll exclude from consideration those who are on a very low income, those who are subject to Division 293 tax (incomes over $250,000) and those who are already at or near the concessional contribution cap. We’ll also assume that all income derives from employment. Finally, in the interests of simplicity, we’ll assume that the increase takes place in one step rather than being staged over several years.

It is highly likely that employer bargaining power is such that increasing the SG contribution rate will not affect total income packages (i.e. gross income plus SG contributions). The calculations below assume that this is so – it is a key assumption of this paper.

Note, however, that in real life salary negotiations are not necessarily cut and dried. So, a push to restore a previous total package value might not be immediate but be buried in subsequent increments, or it might manifest as additional pressure in future negotiations.

To be able to work this through mathematically, however, we make the simplifying assumption that incomes will adjust immediately.

It’s also important to keep in mind that while a mathematical model produces precise, neat and tidy results, these are only as good as the initial assumptions – the real world is much messier. The important function of an analysis such as this one is not so much to produce precise predictions, but rather to lay bare the way in which key variables (in this instance: income, income tax, SG rate and contribution tax) all interact. Better understanding should lead to better decision making.

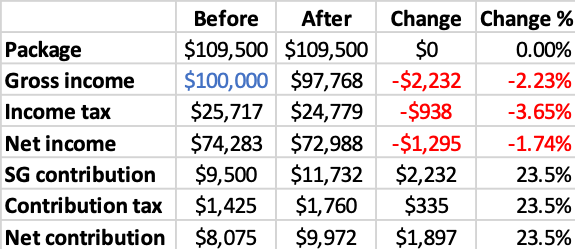

With these cautions in mind, let’s move on. Some straightforward arithmetic, illustrated in Table 1, shows that the immediate consequences of increasing the SG rate will be as follows:

- SG contributions will rise by 23.5%

- Gross incomes will fall by 2.23%

- Net SG contributions will rise by 23.5%, corresponding to 1.90% of initial gross income

- Government income tax receipts will fall by an amount which depends on income.

Table 1 shows how the numbers work out for an initial gross income of $100,000:

Table 1

- The top line reflects the assumption of no change in the total income package

- so, there must be a drop in gross income (2nd line)

- and therefore, the government’s income tax receipts will fall (3rd line)

- as will the individual’s net income (4th line).

- The SG contribution goes up by 23.5% (5th line).

- The government claws back an extra 23.5% contributions tax (6th line)

- leaving a net contribution which is also 23.5% higher than before (7th line).

In summary, the superannuation account of the individual currently earning $100,000 nets an extra $1,897 per year. In the short term, this is a zero-sum game (the savings have to be paid for): $1,295 is provided by the individual (reduced net income offset by lower income tax) and $603 is provided by the government (reduced income tax receipts offset by higher contribution tax).

In other words, the individual saves more, and the government also contributes.

Although this is a zero-sum game in the short term, that is not the case in the long term. Superannuation savings provide a massive investment resource for the nation, and a more financially secure retiree population will require less government support. There is a large net benefit to the nation from supporting and incentivising long-term saving.

Although Table 1 is worked for $100,000 initial gross income, the same 2.23% fall in gross income and 23.5% increase in net SG contribution occurs for any other initial income.

The boost to SG contributions then flows through to provide a valuable 23.5% increase in the value of SG contributions and their accumulated investment returns at any time through to retirement, and consequently the same percentage increase in both earnings and earnings tax.

A partial response to Issue 2(b), therefore, is: yes, the planned increase in SG rate will depress gross incomes by 2.23%.

5 How is the cost shared between government and individual?

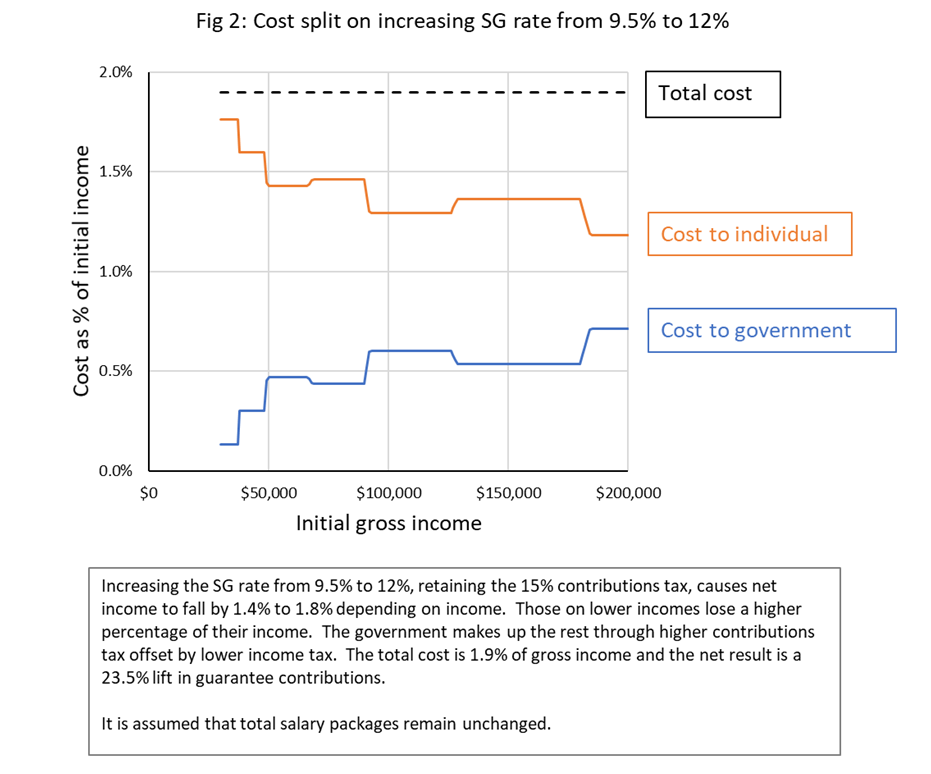

Before the increase, the net SG contribution is 8.075%, after allowing for the 15% contributions tax, so a 23.5% increase in that corresponds to 1.90% of the initial gross income. That 1.90% must be paid for, and as we have seen the cost is shared between the individual and the government.

Fig 2 shows the split for a wide range of initial incomes, the structure in the graphs reflecting the complicated structure of income tax rates.

The cost to government averages about 0.5% of gross income (for incomes between $50,000 and $180,000) and that helps put Issue 2(d) in context: it is of similar magnitude to a modest income tax reduction.

The cost should not be onerous for the government and could be funded by cancelling or reducing less important programs, or by working with greater efficiency (meant literally, not as a euphemism for sacking people which only pushes costs back to individuals).

Incidentally, the cost to government is sometimes compared to the cost of fixing other significant problems, such as Newstart. This is the wrong way to evaluate the priority of a project: it should be compared to the least important project, which can most easily be dropped, not to other important projects.

6 How quickly will the effects be felt?

The effects on net income and taxes discussed above will be immediate, but the impact on retirement income will take time to evolve – about a decade for effects to become noticeable and four decades for the complete benefit.

Superannuation operates over the very long term, which means the sooner problems are fixed the better. The current financial climate does not justify delay.

Two issues which will eventually emerge but will be insignificant for the first couple of decades are:

- Earnings taxes on superannuation investments will increase by 23.5%.

- Age pension entitlements will decrease for people on low-to-moderate-incomes.

Both benefit the government. However, the age pension needs significant modification to correct other fundamental problems:

- The asset test taper rate is unreasonably high, and this is the direct cause of the concern expressed in Issue 2 (c). The issue has been widely discussed, for example see https://saveoursuper.org.au/retirement-income-savings-trap-caused-coalitions-2017-superannuation-age-pension-changes/

- Inappropriate indexing creates inbuilt instabilities in the age pension which will make it harder to get and less generous in the future. This is a little-known but serious long-term structural deficiency. See https://saveoursuper.org.au/wp-content/uploads/Retiree-time-bombs.pdf

In short, there is plenty of time and opportunity to make sure that Issue 2(c) will not become a problem.

7 An alternative proposal

The above calculations highlight something quite bizarre about concessional superannuation contributions: the superannuation guarantee compels people to save for their retirement, but the contributions tax immediately undermines that – now you see it, now you don’t!

The system would be much neater and easier to understand if the contributions tax were abolished.

That would also make voluntary concessional contributions (up to the cap) more attractive, thus encouraging more saving, but let’s look more closely at what it would mean for compulsory SG contributions.

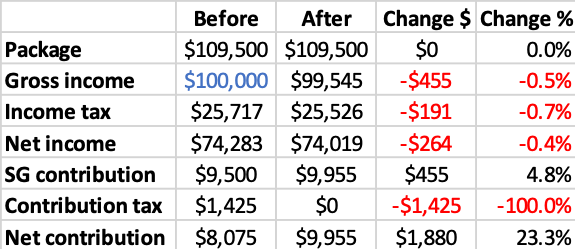

As we have seen the upcoming increase in SG rate will increase compulsory net contributions to superannuation by 23.5%, given the assumption that gross incomes are unaffected, so let’s take that as an objective and see how it would be achieved without the contributions tax.

The answer is that the SG rate then only needs to be increased to 10%, rather than 12%. Net contributions will increase by 23.3% which is almost identical to 23.5%, but the split in cost between the government and individual is changed significantly.

Table 2 shows the detailed figures for a gross income of $100,000:

Table 2

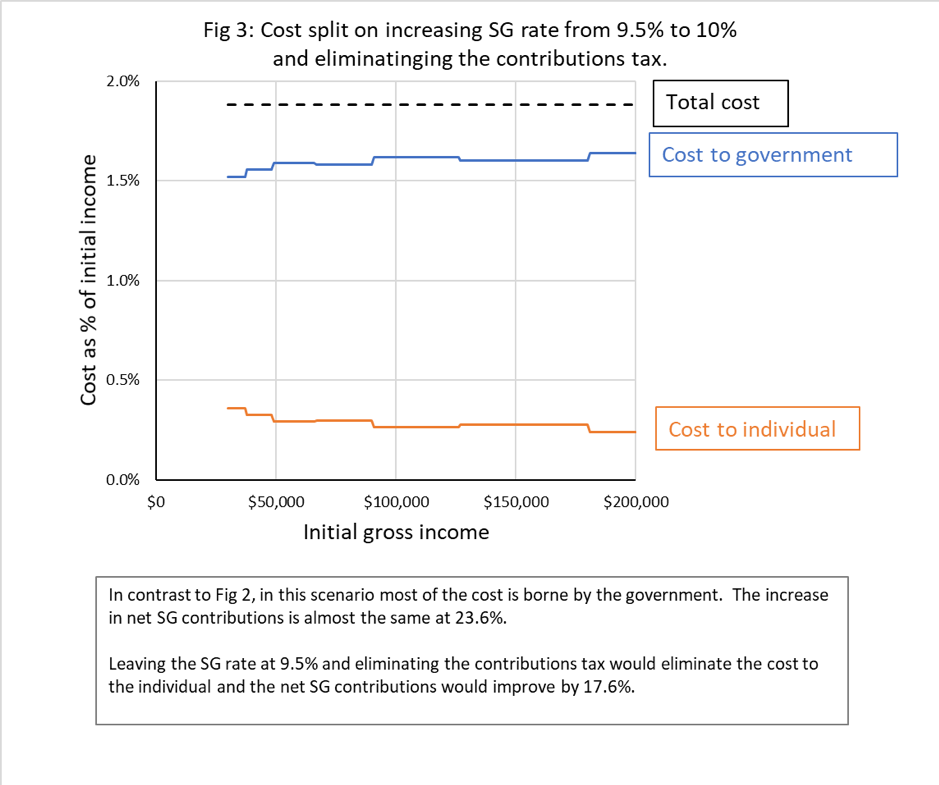

and Fig 3 shows the split in costs between government and individual for a range of gross incomes:

From the government’s point of view, this proposal is more expensive by about 1% of gross income than the increase currently legislated – it is still the equivalent of a modest tax cut across the board. Staging this change over several years would further reduce the budgetary shock.

From the individual’s point of view, the cost has reduced to about a quarter of a percent of gross income, which in normal times most people would not notice.

However, these are not normal times: the aftermath of this summer’s fires and the developing coronavirus scenario mean that many people are or will be under severe financial pressure. The government is currently working to provide significant stimulus in response. The government has also reportedly asked ANU to advise the government on whether the upcoming increase will affect incomes.

As shown above, they certainly will do so, and it is tempting to see this as a strong argument against making any increase at all.

However, it is easy in times of crisis to neglect long term issues, banking problems for future generations.

The government could find it attractive, therefore, to demonstrate a continued commitment to long term saving by dropping the contributions tax, while leaving the SG rate at 9.5% so there is no additional cost for individuals.

If that approach is followed, the boost to net SG contributions will be 17.6% instead of 23.5% – a little less, but still a sizeable improvement for the long term.

To see what that would mean, we return to Fig 1 and consider someone who chooses a “Balanced” investment option for their super. Using ASIC’s figures, that would give a replacement ratio of 20% under the current rules for the assets derived from SG contributions.

The initial retirement income would thus be 24.7% of final employment income under the current plan (23.5% improvement), or 23.5% of final employment income if the SG rate remains at 9.5% and the contributions tax is dropped (17.6% improvement). Either way, it is a significant improvement, while still leaving a considerable gap to be filled by extra voluntary saving, or the age pension, depending on the retiree’s circumstances.

8 About the author

Jim Bonham (BSc (Sydney), PhD (Qld), Dip Corp Mgt, FRACI) is a retired scientist (physical chemistry). His career spanned 7 years as an academic followed by 25 years in the pulp and paper industry, where he managed scientific research and the development of new products and processes. He has been retired for 14 years and has run an SMSF for 17 years. He will not be affected by any change to the superannuation guarantee.

***************************************************

Superannuation funds in $400m message

The Australian

19 February 2020

Michael Roddan – Reporter

Australia’s largest superannuation funds have spent close to $400m on advertising, stadium naming rights and sport sponsorship over the past five years in a bid to get a bigger slice of workers’ compulsory savings.

The figures, which provide an insight into the spending habits of a handful of the country’s 200 super funds, come amid a fierce industry debate about whether the current 9.5 per cent of worker wages being set aside for the retirement system will be adequate to maintain living standards in retirement.

An analysis of parliamentary disclosures by The Australian has found nine of Australia’s biggest super funds have spent $384m on advertising campaigns, sponsorship of sports teams and stadiums, marketing and brand research since the 2015 financial year.

This includes more than $100m spent by the country’s largest fund, AustralianSuper, on marketing, brand promotion and media broadcasting over the past five years. Over the same period, AustralianSuper also shelled out a further $24m to the not-for-profit super sector’s lobbying and research arm, Industry Super Australia, which runs its own advertising campaigns, including one launched this month calling on the government not to dump the scheduled increase in the superannuation guarantee from 9.5 per cent to 12 per cent, reportedly at a cost of $3.5m.

Hostplus, which manages the savings of hospitality and tourism workers, has spent more than $60m on brand advertising, along with an extra $18.5m on payments to Industry Super Australia, since the 2015 financial year.

Disclosures made to the House of Representatives’ economics committee, in response to questions on notice from Liberal MP Tim Wilson, also cover submissions from the construction workers industry fund, Cbus, which spent $48m on a number of brand advertising ventures over the same period.

Cbus, Hostplus and AustralianSuper attract a large degree of their membership from having won “default” fund status with employers through enterprise bargaining agreements, which means workers who fail to nominate their own super fund will have their savings managed by the default provider.

Super trustees are required by law to only spend money in members’ best interests and for the sole purpose of providing benefits to members when they retire.

Advertising spending is not unlawful, and is monitored by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. The super industry argues building brand awareness and attracting new members helps drive economies of scale that support the efficient growth of retirement savings for their members. However, only about 3 per cent of super members switch funds each year, while about 80 per cent of new employees do not make an active choice and go with the default selection chosen by their employer.

Cbus outlined a number of advertising campaigns, including a five-year, $30m “brand campaign”, a program targeting younger members, and another bolstering its status in Queensland where the rival BUSSQ super fund manages the savings of workers in the construction industry. Firms paid to keep track of Cbus’s spending include Kantar TNS, Nielsen Sports, Empirica Research, CoreData and Essential Research.

The $57bn Hostplus said its brand advertising included “advertising on television, radio, online billboards and on public transport”, sponsorship of logos on sports teams and “advertising on stadium signage scoreboards” and sending mail, emails and text messages to its members.

“The promotional activity of Industry Super Australia includes advertising on television, online, on radio, in the press and on billboards,” Hostplus said.

Australian Super, which manages $180bn, told parliament it tracks the “efficacy of campaigns in either retaining or gaining new members” for each of its campaigns.

The for-profit retail super sector has also spent millions on marketing, including Commonwealth Bank’s superannuation arm Colonial First State, which spent $22m over five years on advertising campaigns.

CBA only invited ad agencies Leo Burnett and IKON to compete for contracts, and only awarded contracts to those two firms, but said it commissioned KPMG to “track brand awareness and consideration over time and report this on a monthly basis”.

This includes placing ads during the Tour de France, money for a “content partnership” campaign with The Guardian online newspaper and a series with Fairfax media titled The Road Next Travelled.

National Australia Bank’s wealth management arm, MLC, spent more than $22m on marketing, about half of which was attributed to the superannuation arm, NULIS, on campaigns such as Save Retirement between 2014 and 2016, and Life Unchanging between 2017 and last year.

“The objective of both campaigns was to drive client and member engagement in their retirement savings and all aspects of proactive wealth management, while positioning MLC as a prospective partner as they seek to save for and live well in retirement,” said NULIS, which was exposed by the royal commission for charging some of the steepest fees while delivering the lowest returns in the $2.9 trillion superannuation sector.

Rest Super, which manages the savings of retail employees and derives most of its membership through the default system, said it had spent $30m over the past five years on advertising. REST has employed creative firms Carat Australia, Customedia, Arnold Furnace, Mr Wolf and Bauer Media Group.

“Rest engage a consultant to provide performance reports on advertising brand campaigns, which is presented to the Rest Board Member and Employer Services Committee,” Rest said.

QSuper, which manages the savings of Queensland public servants, spent $31m on advertising, promotion and direct marketing, while StatePlus, which looks after the nest eggs of NSW public servants, spent almost $10m on ad campaigns and sponsorship over the past five years.

“A strong focus of QSuper’s current direct marketing to members is financial wellbeing,” QSuper said.

“This includes informing and educating members on the value of financial advice, educational seminars and insurance — that is, services which aim to improve the financial literacy and retirement outcomes of our members. While this may be categorised as marketing it may also reasonably be categorised as education of QSuper members of their retirement options and opportunities.”

StatePlus, which has contracted creative agencies 303MillenLow, the Lexicon Agency and Reef Digital Media to run its marketing campaigns, has spent a little over $9m since the 2017 financial year.

“StatePlus runs always-on above-the-line and below-the-line campaigns with the objective of building brand awareness and consideration and generate new members to the fund,” said StatePlus, which looks after the savings of NSW public sector employees.

It noted its brand awareness increased by 44 per cent, and its “informed awareness” level rose by 58 per cent following the advertising.

Super chance for a policy rethink

The Australian

8 February 2020

Katrina Grace Kelly – Columnist

The result of last year’s federal election is described as a miracle, but I prefer to deal in facts. So, if we examine a long list of facts and sum them up in a few words, the Coalition didn’t win the election, Labor lost it.

And the reason Labor lost, again summing up a long list of facts, is because it gave the impression that it was going after people’s ability to create and preserve personal wealth.

Mind you, before the election the Coalition also had given the community this impression with its superannuation changes. However, the Coalition came after the retirement savings of the self-funded, and therefore only a certain number of people in a certain age category felt assaulted. When the time came, as much as those people wanted to object at the ballot box, anger probably gave way to fear of something even worse.

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, and now senior thinkers in the government have engaged in some reflection. A few grudging concessions have been muttered; there is acceptance that the government went too far and that some of the adverse superannuation changes have been counter-productive.

So, there is a desire to undo some of the damage, as long as the government isn’t seen to be unwinding its changes. It wants a remedy that isn’t a backflip, a retreat without an undoing. In other words, the government wants to give the cake back that it has already eaten, without the indignity of regurgitation.

A government review into something can cover a thousand sins and provide enough justification for anything. It is just fortuitous then, isn’t it, that Treasury has commissioned a retirement income review that is tasked with “establishing a fact base to help improve understanding of how the Australian retirement income system is operating and how it will respond to an ageing society”.

The independent panel leading the review released a consultation paper last year and this week the timeframe for submissions passed.

The review is due to report by June, and if there is a pathway to redemption then here is where we will find it. The clues to this intention are sprinkled right throughout the consultation document.

A section headed “Changing trends and one-off shocks” admits “the trend in interest rates … has (continued), and may continue, to affect the public cost of the retirement income system through changes in the social security deeming rates and the interest rate used by the Pension Loans Scheme”. One consultation question asks: “What factors should be considered in assessing how the current settings of the retirement income system (eg tax concessions, superannuation contribution caps and Age Pension means testing) affect its fiscal sustainability?”

There is an opportunity here, then, to remedy a past error.

In a low interest rate environment, the self-sufficient need far more money than anyone imagined. We need to relax the contribution caps and allow people to shovel their savings into superannuation. Unfortunately, the idea of people creating wealth for themselves causes policymakers to break out in hives.

The paper says “the tax advantaged status of superannuation may encourage some individuals to partly use superannuation for wealth accumulation and estate planning rather than solely for retirement income purposes.”

What a shame that everybody cannot organise themselves to save precisely the right amount for their retirement and then promptly drop dead the minute they’ve spent it, ensuring there is nothing left over.

Spare a thought now for politicians and Treasury, who are tortured by two competing desires. On the one hand, they don’t want to bear the cost of people on the pension but, on the other, they don’t want people to be too wealthy either.

Perhaps the only thing worse than the poor who require support are the rich who generate envy. Maybe this is why there is the endless search for the in-between solution, one that brings comfort but cannot possibly exist: the not-too-poor but not-too-rich perfect retiree.

In a global free market with a fluid cost of living, the measure of what is needed to be self-funded will always change. Therefore, it is impossible to keep people down to a level of poverty that is just above the level where they require government support.

Fundamentally, nothing of substance will ever be achieved in the retirement savings space unless the government comes to terms with the following: if you don’t want people on the pension, you must allow them to create their own wealth. Tax some of it if you will, but at least allow it to be created.

Further, it is time our political class accepted that superannuation is a wealth-creation vehicle. It should be a wealth-creation vehicle. It must be a wealth-creation vehicle, for if retirees are not going to be poor enough to go on the pension, then they must be too rich to go on the pension, by a long way, because the market can easily erode a slim margin.

Governments of all persuasions, but especially a Coalition government, must get over their squeamish reaction to the idea that people are using their superannuation to create wealth because that is exactly what superannuation is for.

Retirement should be about more than just ‘getting by’

The Age

2 February 2020

Eva Scheerlinck

More than 100 years ago, female factory workers in Chicago campaigned for the right to vote and wondered how it could deliver them not only a “living wage” but life’s roses.

Their catchphrase,‘Bread for all and roses too’ – with bread representing home, shelter and security and the roses representing music, education, nature and books – went on to inspire generations of American women, particularly those involved in industrial action during the 1930s.

The notion that the humblest workers have a right to live, not just exist, is just as relevant today. Australia is one of the wealthiest nations on Earth and we all deserve a share of the enormous economic gains of the past century.

This includes retirees, many of whom struggle to make ends meet. And it should be a central discussion point for the Federal Government’s Retirement Income Review, currently under way.

There is no stated objective for our retirement income system in our law. However, the community has strong views on what the objective and features of our retirement income system should be.

Research commissioned by Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees (AIST) found that more than eight in 10 Australians believe the government should make sure super and the age pension are set high enough so that all Australians have a decent life, free of financial stress, in retirement. This finding is consistent across education levels, geographic location, and voting preference.

Our polling suggests that what most people want in retirement is no different to what the Chicago suffragettes wanted – to enjoy life, not just “get by”. For most ordinary older Australians this means being able to enjoy a weekly coffee and cake with friends, to afford home maintenance, the internet, a car or a footy club membership. They’re not asking for gilded luxury.

In the lead-up to the Retirement Income Review, it’s been suggested that the government’s legislated timeline to increase the compulsory super rate to 12 per cent by 2025 should be halted because the current super rate is enough.

But the modelling done by some researchers who reached this conclusion was based on a full-time male earning above median wages working continuously for 40 years. This is not the lived experience of a great many Australians – potentially more than half the working population. This includes women taking time out of paid work to care for children and family, low-income earners, those priced out of home ownership, many Indigenous Australians, single people and a large cohort who retire involuntarily due to ill health or the inability to find a job in later years.

It has also been argued by some – including a group of Coalition MPs (who, incidentally, receive more than 14 per cent super from their employer) that low-income earners should be excluded from compulsory super and left to fend on the age pension. Meanwhile, the Save our Super lobby group – which also argues that a super rate of 12 per cent is too high for people on low incomes – has called for the $1.6 million tax-free cap on pension accounts to be abolished or raised to boost retirement income for Australians with more than this amount in their super.

There is no shortage of opinions on how super and the age pension should work together. Despite the age pension having been around since the early 1900s and compulsory super for three decades, we still lack consensus on whether super is there to supplement or substitute the age pension. But surely one thing we should all agree on is that in egalitarian Australia, the land of the fabled fair go, all Australians, regardless of income or address, have contributed to our nation’s success and deserve a decent life when they finally lay down their tools.

Eva Scheerlinck is CEO of the Australian Institute of Superannuation Trustees.

Call to grandfather super changes, abolish $1.6m contributions cap

The Australian

27 January 2020

Glenda Korporaal – Associate Editor (Business)

The Save Our Super lobby group has called on the federal government to grandfather any future negative changes to superannuation and abolish the $1.6m cap on the amount of money that can go into tax-free super retirement accounts.

In its submission to the federal government inquiry into retirement incomes, Save Our Super argues that the fall in interest rates since the 2016 budget has significantly reduced the income retirees can earn from savings since the $1.6m transfer cap was announced.

The submission argues that the cap, which was announced as part of a broad package of changes, including cuts to super contribution limits, should be either abolished or raised.

“The interest earnings from $1.6m is now almost 40 per cent lower than it was in early 2016,” the submission says.

“With the continuing drift of interest rates towards zero, whatever unexplained calculations arrived in 2016 at the $1.6m on the superannuation in retirement phase should be re-examined with a view to grandfathering the cap, raising it or abolishing it.”

Save Our Super was set up to lobby against the 2016 budget changes to super by a group including retired Melbourne QC Jack Hammond.

The organisation has consistently argued that it is a basic principle of the Australian taxation system that there should be no negative retrospective changes to tax and superannuation.

The 2106 changes were announced after the Tony Abbott-led Coalition went to the polls in the election of September 2013 promising not to make any negative changes to super during the first term of its government.

The Save Our Super submission argues any future negative changes to super must be grandfathered so that “those people who committed in good faith to lawfully build their life savings are not blindsided by policy changes with effectively retrospective effects”.

“Citizens need assuring that any future changes in policy will not have any significantly adverse effects on lawful prior savings,” it says.

Federal Treasurer Josh Frydenberg announced a review of retirement incomes policy last September.

The review is expected to report in June this year.

The SOS submission argues that the current compulsory super system should be recognised as a success in encouraging saving for retirement in Australia and reducing the number of people on the full Age Pension.

It argues that any assessment of the impact of super policies should consider the benefits of the compulsory super system and not just the narrow annual cost of super tax concessions.

“Instead of cost-benefit work, we see reporting which highlights only the estimated gross costs of retirement policy — expenditures on the aged pension plus problematic estimates of the ‘tax expenditures’ on superannuation,” it says.

“There is no measure anywhere of the fiscal and broader economic benefits in moving, over time, significant numbers of those age-eligible for the pension to a higher living standard in self-funded retirement from increased saving,” it says.

It argues that the review’s “highest priority” should be in establishing a fact base on the situation around retirement income in Australia that would include long-term economic modelling of retirement income trends and their social costs and benefits.

It argues that the current focus on the tax forgone from super tax concessions is “misleading” and “hugely overstates gross costs” and ignores other positive outcomes such as encouraging saving for retirement and reducing a potential drain on the Age Pension.

The submission also argues for a reform of the current compulsory super guarantee system.

It says the compulsory 9.5 per cent contribution to super, which is set to rise to 12 per cent, is too high for people on low incomes.

It says the current income level threshold for super contributions has been kept at the low level of $450 a month — a level set when the super guarantee system was introduced at 3 per cent in 1992.

Save Our Super submission: Consumer Advocacy Body for Superannuation

Click here for the PDF document

13 January 2020

The Manager

Retirement Income Policy Division

Treasury

Langton Cres

Parkes ACT 2600

Save Our Super submission: Consumer Advocacy Body for Superannuation

Dear Sir/Madam

Save Our Super has recently prepared an extensive Submission to the Retirement Income Review dealing in part with the many ‘consumer’ issues triggered by the structure of retirement income policy and the frequent and complex legislative change to that policy.

That Submission was lodged with the Review’s Treasury Secretariat on 10 January 2020 and a copy is attached to the e-mail forwarding this letter. It serves as an example of the analysis of super and retirement policy and of the advocacy that superannuation fund members, both savers and retirees, can contribute. Its four authors’ backgrounds show the wide range of experience that can be useful in the consumer advocacy role.

We note both the policy and the advocacy consultations are running simultaneously, exemplifying the pressures Government legislative activity places on meaningful consumer input. Consumer representation is necessarily more reliant on volunteer and part-time contributions than the work of industry and union lobbyists and the juggernaut of government legislative and administrative initiatives.

Given the breadth, complexity and fundamentally important nature of the issues raised for the Retirement Income Review by its Consultation Paper, we have prioritised our submission to that Review over the issues raised by the idea of a Consumer Advocacy Body. This letter serves as a brief submission and as a ‘place holder’ for Save Our Super’s interest in the consumer advocacy issues.

The idea of a consumer advocacy body is worthwhile in trying to improve member information, engagement and voice in superannuation and in the formation of better, more stable and more trustworthy retirement income policy. It should help government to understand the perspectives of superannuation members.

Save Our Super was formed from our frustration at the evolution of superannuation and broader retirement income policies. We contributed as best we could to the rushed and heavily constrained Government consultations on, and Parliamentary Committee inquiries into, the complex retirement income policy changes that took effect in 2017. One example of our inputs is https://saveoursuper.org.au/save-supers-joint-submission-senate-committee-two-superannuation-bills/ .

For the consultations on the Consumer Advocacy Body for Superannuation, we limit our comments here to point 1 on the Consultation’s brief web page, https://treasury.gov.au/consultation/c2019-38640 :

“Functions and outcomes: What core functions and outcomes do you consider could be delivered by the advocacy body? What additional functions and outcomes could also be considered? What functions would the advocacy body provide that are not currently available?”

Key roles

- Consult with superannuation fund members on their concerns, including issues of legal and regulatory complexity, frequent legislative change and legislative risk which has become destructive of trust in superannuation and its rule-making.

- Commission or perform research arising from consultations and reporting of member concerns.

- Tap perspectives of all superannuation users, whether young, mid-career, or near-retirement savers, as well as of part- or fully self-funded retirees.

- Publish reporting of savers’ concerns to Government, at least twice-yearly and in advance of annual budget cycles.

- Contribute an impact statement – as envisaged in the lapsed Superannuation (Objectives) Bill – of the effects of changes to any legislation (not just super legislation) on retirement income (interpreted broadly to include the assets, net income and general well-being of retirees, now and in the future).

The advocacy body should:

- take a long-term view, and could be made the authority to administer, review or critique the essential modelling referred to in Save Our Super’s submission to the Retirement Income Review. Ideally, the Consumer Advocacy Body should have the freedom to commission Treasury to conduct such modelling, and/or to use any other capable body.

- give appropriate representation and support to SMSFs, and be prepared to advocate for them against the interests of large APRA-regulated funds when necessary.

- advocate specifically for the very large number of people with quite small superannuation accounts, when their interests are different from those of people with relatively large balances.

The biggest risk to the advocacy body in our view is that it would over time be hijacked by special interest groups, or hobbled by its terms of reference. Careful thought in its establishment, key staffing choices and strong political support would be helpful to protect against these risks.

Membership issues

- Membership of the Body should be part-time, funded essentially per diem and with cost reimbursement only for participation in the information gathering and consumer advocacy processes. A small part-time secretariat could be provided from resources in, say, PM&C or Treasury.

- Membership opportunities should be advertised.

- Membership of the Body should be strictly limited to individuals or entities that exist purely to advocate for the interests of superannuation fund members. (This would include any cooperative representation of Self-Managed Superannuation Funds.) We would counsel against allowing membership to industry entities which might purport to advocate on behalf of their superannuation fund members, but might also inject perspectives that favour their own commercial interests.

- Membership should include individuals with membership in (on the one hand) commercial or industry super funds and (on the other hand) Self-Managed Superannuation Funds. We see no need to ensure equal representation of commercial and industry funds, though we would be wary if representation was only of those in industry funds or only commercial funds.

- We offer no view at this stage on whether the Superannuation Consumers Centre would be a useful anchor for a new role, but we would suggest avoiding duplication.

Functions not currently available

The consultation asks what functions the Consumer Advocacy Body for Superannuation could perform that are not presently being performed. SOS’s submission to the Retirement Income Review and earlier submissions on the changes to retirement income policy that took effect in 2017 shows the range of superannuation members’ advocacy concerns that are not at present being met.

Prior attempts to establish consultation arrangements for superannuation members appear to us to have focussed mostly on the disengagement and limited financial literacy of some superannuation fund members. Correctives to those concerns have heretofore looked to financial literacy education and better access to higher quality financial advice. Clearly such measures have their place.

But in the view of Save Our Super, these problems arise in larger part from the complexity and rapid change of superannuation and Age Pension laws, and in the nature of the Superannuation Guarantee Charge. Nothing predicts disengagement by customers and underperformance and overcharging by suppliers more assuredly than government compulsion to consume a product that would not otherwise be bought because it is too complex to understand, too often changed and widely distrusted.

There needs to

be more consumer policy advocacy aimed at getting the policies right, simple,

clear and stable, as was attempted in the 2006 – 2007 Simplified Super reforms.

Other issues

In the time available, we offer no views on questions 2,3 and 4, which are more for government administrators.

Yours faithfully

Jack Hammond, QC

Founder, Save Our Super

Submission by Save Our Super in response to Retirement Income Review Consultation Paper – November 2019

Submission by Save Our Super in response to Retirement Income Review Consultation Paper – November 2019

by Terrence O’Brien, Jack Hammond, Jim Bonham and Sean Corbett

10 January 2020

Click here for the full PDF document

Summary

- The Review’s Terms of Reference seek a fact base on how the retirement income system is working. This is a vital quest. Such information, founded on publication of long-term modelling extending over the decades over which policy has its cumulative effect, has disappeared over the last decade.

- Not coincidentally, retirement income policy has suffered from recent failures to set clear objectives in a long-term framework of rising personal incomes, demographic ageing, lengthening life expectancy at retirement age, weak overall national saving, low household and company saving and a persistent tendency to government dissaving.

- A new statement of retirement income policy objectives should be:

-

- to facilitate rising real retirement incomes for all;

- to encourage higher savings in superannuation so progressively more of the age-qualified can self-fund retirement at higher living standards than provided by the Age Pension;

- to thus reduce the proportion of the age-qualified receiving the Age Pension, improving its sustainability as a safety net and reducing its tax burden on the diminishing proportion of the population of working age; and

- to contribute in net terms to raising national saving, as lifetime saving for self-funded retirement progressively displaces tax-funded recurrent expenditures on the Age Pension.

- With the actuarial value of the Age Pension to a homeowning couple now well over $1 million, self-funding a higher retirement living standard than the Age Pension will require large saving balances at retirement. It is unclear that political parties accept this. It seems to Save Our Super that politicians champion the objective of more self-funded retirees and fewer dependent on the Age Pension but seem dubious about allowing the means to that objective.

- Save Our Super highlights fragmentary evidence from the private sector suggesting retirement income policies to 2017 were generating a surprisingly strong growth in self-funded retirement, reducing spending on the Age Pension as a share of GDP, and (prima facie) raising living standards in retirement (Table 1). (Anyone who becomes a self-funded retiree can be assumed to be better off than if they had rearranged their affairs to receive the Age Pension.) Sustainability of the retirement system for both retirees and working age taxpayers funding the Age Pension seemed to be strengthening. These apparent trends are little known, have not been officially explained, and deserve the Review’s close attention in establishing a fact base.

- Retirement policy should be evaluated in a social cost-benefit framework, in which the benefits include any contraction over time in the proportion of the age-eligible receiving the Age Pension, any corresponding rise in the proportion enjoying a higher self-funded retirement living standard of their choice, and any rise in net national savings; while

the costs include a realistic estimate of any superannuation ‘tax expenditures’ (this often used term is placed in quotes because it is generally misleading – see subsequent discussion) that reduce the direct expenditures on the Age Pension. Such a framework was developed and applied in the 1990s but has since fallen into disuse.

- Policy changes that took effect in 2017 have suffered from a lack of enumeration of the long-term net economic and

fiscal impacts on retirement income trends. They also damaged confidence in the retirement rules, and the rules for changing those rules. Extraordinarily, many people trying to manage their retirement have found legislative risk in recent years to be a greater problem than investment risk. Save Our Super believes the Government should re-commit to the grandfathering practices of the preceding quarter century to rebuild the confidence essential for long-term saving under

the restrictions of the superannuation system.

- Views on whether retirement policy is fair and sustainable differ widely, in large part because the only official analysis that has been sustained is so-called ‘tax expenditure’ estimates using a subjective hypothetical ‘comprehensive income tax’ benchmark that has never had democratic support.

- This prevailing ‘tax expenditure’ measure is unfit for purpose. It is conceptually indefensible; it produces wildly unrealistic

estimates of hypothetical revenue forgone from superannuation (now said to be $37 billion for 2018-19 and rising); and it presents an imaginary gross cost outside the sensible cost-benefit framework used in the past. It also presents (including, regrettably, in the Review’s Consultation Paper) an imaginary one-off effect as though it could be a

recurrent flow similar to the actual recurrent expenditures on the Age Pension.

- An alternative Treasury superannuation ‘tax expenditure’ estimate, more defensible because it has the desirable characteristic of not discriminating against saving or supressing work effort, is based on an expenditure tax benchmark. It estimates annual revenue forgone of $7 billion, steady over time, not $37 billion rising strongly.

- Additional to the four evaluative criteria proposed in the Consultation Paper, Save Our Super recommends a fifth: personal choice and accountability. Over the 70-year horizon of individuals’ commitments to retirement saving, personal circumstances differ widely. As saving rates rise, encouraging substantial individual choice of saving profiles to achieve preferred retirement living standards is desirable.

- We also restate a core proposition perhaps unusual to the modern ear: personal saving is good. The consumption that is forgone in order to save is not just money; it is real resources that are made available to others with higher immediate demands for consumption or investment. Saving and the investment it finances are the foundation for rising living standards. Those concerned at the possibility of inequality arising from more saving should address the issue directly by presenting arguments for more redistribution, not by hobbling saving.

- While retirement income ‘adequacy’ is a sensible criterion for considering the Age Pension, ‘adequacy’ makes no sense as a policy guide to either compulsory or voluntary superannuation contributions towards self-funded retirement. Adequacy of self-funded retirement income is properly a matter for individuals’ preferences and saving choices.

- The task for superannuation policy in the broader retirement income structure is not to achieve some centrally-approved

‘adequate’ self-funded retirement income, however prescribed. It is to roughly offset the government’s systemic disincentives to saving from welfare spending and income taxing. Once government has struck a reasonable, stable and sustainable tax structure from that perspective, citizens should be entitled to save what they like, at any stage of life.

- The Super Guarantee Charge’s optimum future level is a matter for practical marginal analysis rather than ideology. Would raising it by a percentage point add more to benefits (higher savings balances at retirement for self-funded retirees) than to costs (e.g. reduced incomes over a working lifetime, more burden on young workers, or on poor workers who may not save enough to retire on more than the Age Pension)?

- The coherence of the Age Pension and superannuation arrangements is less than ideal. Very high effective marginal tax rates on saving arise from the increased Age Pension assets test taper rate, with the result that many retirees are trapped in a retirement strategy built on a substantial part Age Pension. Save Our Super also identifies six problem areas where inconsistent indexation practices of superannuation and Age Pension parameters compound through time to reduce super savings and retirement benefits relative to average earnings. These problems reduce confidence in the stability of the system and should be fixed.

- Our analysis points to policy choices that would give more Australians ‘skin in the game’ of patient saving and long term investing for a well performing Australian economy. Those policies would yield rising living standards for all, both those of working age and retirees. Such policies would give more personal choice over the lifetime profile of saving and retirement living standards; fewer cases where compulsory savings violate individual needs, and more engaged personal oversight of a more competitive and efficient superannuation industry.

About the authors

Terrence O’Brien is an honours graduate in economics from the University of Queensland, and has a master of economics from the Australian National University. He worked from the early 1970s in many areas of the Treasury, including taxation

policy, fiscal policy and international economic issues. His senior positions have also included several years in the Office of National Assessments, as resident economic representative of Australia at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, as Alternate Executive Director on the Boards of the World Bank Group, and as First Assistant Commissioner at the Productivity Commission.

Jack Hammond LLB (Hons), QC is Save Our Super’s founder. He was a Victorian barrister for more than three decades.

He is now retired from the Victorian Bar. Prior to becoming a barrister, he was an Adviser to Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, and an Associate to Justice Brennan, then of the Federal Court of Australia. Before that he served as a Councillor on the Malvern City Council (now Stonnington City Council) in Melbourne.

Jim Bonham (BSc (Sydney), PhD (Qld), Dip Corp Mgt, FRACI) is a retired scientist (physical chemistry). His career spanned 7 years as an academic followed by 25 years in the pulp and paper industry, where he managed scientific research and the development of new products and processes. He has been retired for 14 years has run an SMSF for 17 years.

Sean Corbett has over 25 years’ experience in the superannuation industry, with a particular specialisation in retirement income products. He has been employed as overall product manager at Connelly Temple (the second provider of allocated pensions in Australia) as well as product manager for annuities at both Colonial Life and Challenger Life. He has a commerce degree from the University of Queensland and an honours degree and a master’s degree in economics from Cambridge University.

******************************************************

Retirement Income Review Consultation Paper (November 2019)

Retirement Income Review Consultation Paper

Retirement Income Review Consultation Paper

November 2019

© Commonwealth of Australia 2019