Author's posts

Tax-free superannuation set to expand with new concessions

The Australian

14 December 2020

James Kirby – Wealth Editor

Superannuation tax concessions are about to expand as an unlikely economic rebound is set to trigger an increase in the amounts that can be held in tax-protected super funds.

Investors should soon be able to have $100,000 more in tax free retirement funds – and contribute a combined $12,500 more into their super annually during working years – as long awaited “indexation” kicks into action over the coming months.

The Australian Taxation Office has issued a public update alerting the finance industry to changing consumer prices which are expected to trigger an expansion of the all-important transfer balance cap – the amount that can be transferred to fund a tax free pension.

In the note the ATO has pointed out that if the Consumer Price Index for the December quarter is 116.9 or higher, “the indexation of the general transfer balance cap will occur on 1 July 2021”. With CPI rebounding in recent months, economists expect CPI will rise beyond this number. At Deloitte Australia, the forecast for the December quarter CPI is 117.

Existing superannuation concessions have been criticised in the wider debate over retirement incomes. The recent Retirement Income Review suggested superannuation concessions were costing the tax system close to $42bn annually. Nonetheless, the expanded limits will be widely welcomed by investors.

Just now the total amount that can be transferred on retirement to super underpinning a tax-free retirement is $1.6 million per individual. That number is set to rise to $1.7m for those who “start their first retirement phase income stream on or after indexation”.

Separately, industry professionals have noted that contribution caps – the amount that can be contributed to super on a pre and post-tax basis – will also receive an indexation-based increase thanks to rising average weekly wages.

At present, the amount that an individual can contribute to super is limited to $25,000 on a pre-tax (concessional) basis and $100,000 on a post tax (non concessional) basis. These amounts are set to rise to $27,500 and $110,000 at the same time next July.

An absurd twist

The changes will also unleash confusion by creating new tiers within superannuation where different people at different ages have different caps on how much they can have funding tax free super.

In a twist that only the absurdly complex super system could come up with, industry professionals have been baffled as to why super caps are indexed in relation to different economic numbers: The CPI and Average Weekly Ordinary Time Earnings (AWOTE). Indexing allows the government to change ‘caps’ as inflation moves higher.

Peter Burgess, deputy CEO and director of policy and education at the Self Managed Super Funds Association, believes that on the basis of the most recent figures it is looking like both caps will go up. “When the government created the system many in the industry said it is going to be very confusing when indexation kicks in. Now, it’s fast approaching,” he says.

In July 2017 the Transfer Balance Cap was introduced as a way to tax the wealthiest users of the super system. Once a person has more than $1.6m in super, the earnings on the amount in excess of $1.6m are eligible for tax: Amounts in excess of $1.6m in the super system are generally taxed at the 15 per cent “accumulation” rate.

The higher Transfer Balance Cap of $1.7m will largely apply to new retirees transferring funds to start a pension.

“We thought the changes might happen in 2020 but COVID-19 put a brake on it. Now investors are surprised at the rebound in the economy and I expect many will be surprised to see the caps lifting as well, “ says Lyn Formica, head of SMSF technical at Heffron.

The Tax Institute Submission | Proportional Indexation of the Personal Transfer Balance Cap

26 August 2020

Senator The Hon Jane Hume

The Assistant Minister for Superannuation, Financial Services and Financial Technology

The Treasury

Langton Cres

Parkes ACT 2600

CC: Robert Jeremenko, Retirement Income Policy Division, The Treasury

By email: senator.hume@aph.gov.au/Robert.Jeremenko@treasury.gov.au

Dear Assistant Minister

Proportional Indexation of the Personal Transfer Balance Cap

The Tax Institute requests the Government to consider the reforms outlined below in relation to Division 294 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) – that is, the transfer balance cap (TBC) provisions.

Division 294 was included as a part of the 2016-17 Federal Budget Superannuation Reforms and introduced a cap on the amount of superannuation benefits an individual could transfer into pension (tax-free retirement) phase. The General TBC was initially set at $1.6 million1 upon commencement from 1 July 2017. The law includes the indexation, in increments of $100,0002, of the TBC in line with movements in the CPI.

Section 294-40 of the ITAA 1997 provides for individuals that have not reached their TBC to access proportional indexation of the TBC in accordance with their unused cap percentage.

The Tax Institute considers that this provision is overly complex and needs to be reformed. In the context of the TBC provisions, The Tax Institute submits that simpler rules would:

- Assist members and their advisers to better understand and manage the TBC; and

- Reduce the cost for both industry participants and the ATO in relation to administering these provisions.

The Institute submits that the removal of proportional indexation will achieve both of these objectives. Accordingly, the Institute’s submission is as follows:

- Abolish proportional indexation of the Personal TBC and adopt standardised indexation in line with movements in the General TBC for individuals that have not maximised their Personal TBC prior to the indexation; or

- If proportional indexation is retained:

- it should be limited, or its application better targeted to individuals that are within close proximity of the General TBC; and

- a permanent relief mechanism should be introduced to allow the Commissioner to disregard inadvertent and small breaches of the Personal TBC and not penalise individuals in cases where the excess transfer balance amount is removed within a specified period of time. There is a precedent that was included in the enabling legislation whereby TBC breaches of less than $100,000 were able to be rectified within 6 months (of the commencement of the legislation) and the breaches would not give rise to the application of notional earnings or an excess transfer balance tax liability3. We suggest adopting this transitional rule permanently (with some modification if required).

The requested reforms have been developed by The Tax Institute’s National Superannuation Technical Committee and are detailed in Annexure A for your consideration.

* * * * *

If you would like to discuss, please contact either me or Tax Counsel, Angie Ananda, on 02 8223 0050.

Yours faithfully,

Peter Godber

President

ANNEXURE A

Overview

Part of the 2016-17 Federal Budget superannuation reforms introduced (from 1 July 2017) a lifetime cap on the amount of accumulated superannuation an individual could transfer into pension (tax-free retirement) phase. The General Transfer Balance Cap (TBC) was initially set at $1.6 million4.

Apart from some specific circumstances prescribed in the law, amounts in excess of the TBC must be withdrawn out of pension phase. The excess amounts could remain either in the accumulation phase with associated earnings taxed at 15 per cent or completely transferred out of the superannuation system. Notably, the General TBC would be indexed and allowed to grow in line with the CPI, in increments of $100,0005.

In addition, a Personal TBC was introduced within the enabling legislation6 which is generally equal to the General TBC applicable at the time when an individual makes their first transfer of capital to a retirement phase income stream.

The ATO administers individual compliance with the TBC via a Transfer Balance Account (TBA).

Proportional indexation

Section 294-40 of the ITAA 1997 provides for proportional indexation of the TBC to allow individuals to benefit from increases in the General TBC where they have not fully expired their entitlement to their Personal TBC.

The structure of proportional indexation, over time, results in individuals having a Personal TBC that differs from the General TBC relative to the time they commence a retirement phase income stream.

Complexity is further added as an individual can only obtain a proportion of each General TBC indexation increase (that is, $100,000), based on their Unused Cap Percentage (UCP).

The UCP applies only if the individual has not fully utilised their Personal TBC and is determined by identifying the individual’s highest TBA balance at the end of a day, at an earlier point in time, and comparing it to their Personal TBC on that day. The UPC is expressed as a percentage and applied against the indexation available for the General TBC. This process is required at each indexation point until such time as the individual utilises 100% of their Cap Space.

Once an individual has used their entire available Cap Space, their Personal TBC is not subject to further indexation, even if they later commute some or all of that pension to bring their TBA balance below their Personal TBC.

This is best illustrated with the following examples (adapted from the Explanatory Memorandum)7:

Example – simple

Danika first commenced an $800,000 retirement phase income stream on 18 November 2017. A Transfer Balance Account is created for her at this time. Her Personal TBC was $1.6m for 2017-18. As Danika had not made any other transfers to her retirement phase account, her highest TBA balance is $800,000. She has used 50% of her $1.6m Personal TBC.

Assuming the General TBC is indexed to $1.7m in 2020-21, Danika’s Personal TBC is increased proportionally to $1.65m. That is, Danika’s Personal TBC is only increased by the UCP of 50% of the $100,000 indexation increase to the General TBC. As such, Danika can now transfer a further $850,000 to commence a retirement phase income stream without breaching her Personal TBC. Notably, earnings on the original $800,000 were not taken into account in working out how much of the unused cap was available.

Example – complex

On 1 October 2017, Nina commenced a retirement phase income stream with a value of $1.2m. On 1 January 2018, Nina partially commuted $400,000 from this income stream to buy an investment property.

Nina’s TBA balance on 1 October 2017 was $1.2m and on 1 January 2018, it was $800,000 (after the $400,000 partial commutation).

In 2020-21, assume the General TBC is indexed to $1.7m. To work out the amount by which Nina’s Personal TBC is indexed, it is necessary to identify the day on which her TBA balance was at its highest. In this case, the highest balance was $1.2m on 1 October 2017. Nina’s Personal TBC on that date was $1.6m. Therefore, as she has used up 75% of her Personal TBC, Nina’s UCP on 1 October 2017 is 25%.

To work out how much her Personal TBC is to be indexed, Nina’s UCP is applied to the amount by which the General TBC has indexed (i.e. $100,000). Therefore, Nina’s Personal TBC in 2020-21 is $1.625m.

In 2022-23, assume the General TBC is indexed to $1.8m (i.e. by another $100,000). As Nina has not transferred any further amount into the retirement phase, her UCP remains at 25%. Her Personal TBC is now

$1.65m (i.e. 25% of the further indexation increase of $100,000). In this year, Nina decides to transfer the maximum amount she can into the retirement phase.

This will be her Personal TBC for the 2022-23 year ($1.65m) less her TBA balance of $800,000. This means Nina can transfer another $850,000 into the retirement phase without exceeding her Personal TBC.

Once Nina has used all of her available Cap Space, her Personal TBC will not be subject to further indexation. Notably, this is the case even if Nina later partially commutes some of her retirement phase income stream and makes her TBA balance fall below her Personal TBC.

Range of Potential Personal TBC

Members (A to D) Cap Space utilised in 2018 – 2021 (assuming indexation in 2021).

| Personal TBC (Start) | Year | Cap Space Accessed | Total Used | Unused Cap %8 | Personal TBC (End) | Year | |

| A | $1,600,000 | 2018 | $1,600,000 | $1,600,000 | Nil | $1,600,000 | 2018 |

| B | $1,600,000 | 2018 | $1,000,000 | $1,000,000 | 38% | $1,638,000 | 2021 |

| C | $1,600,000 | 2018 | $ 700,000 | $ 700,000 | 57% | $1,657,000 | 2021 |

| D | $1,700,000 | 2021 | $1,000,000 | $1,000,000 | N/A | $1,700,000 | 2021 |

Members (A to D) Cap Space utilised in 2022 – 2025 (assuming further indexation in 2025).

| Personal TBC (Start) | Year | Cap Space Accessed | Total Used | Unused Cap % | Personal TBC (End) | Personal TBC Year | |

| A | $1,600,000 | 2022 | Nil | Nil | Nil | $1,600,000 | 2025 |

| B | $1,638,000 | 2022 | $ 500,000 | $1,500,000 | 9% | $1,647,000 | 2025 |

| C | $1,657,000 | 2022 | $ 900,000 | $1,600,000 | 4% | $1,661,000 | 2025 |

| D | $1,700,000 | 2025 | Nil | $1,000,000 | 42% | $1,742,000 | 2025 |

As illustrated above, the amount of proportional indexation largely depends on an individual’s UCP, each time there is indexation of the General TBC.

The result of this process is an individual’s Personal TBC is likely to be unique to themselves if they are in the category where they do not utilise their full TBC at the point of commencing a retirement phase income stream.

The burden is therefore likely to fall to individuals with smaller superannuation balances.

Current Issues and Challenges

Overly complex calculation and too widely targeted

The above examples demonstrate the complexity of the proportional indexation calculation which, over time, will require very effective record management systems to track and be effective in ensuring individuals are not subject to inadvertent breaches of their TBC.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum9 (EM) to the enabling legislation, the introduction of the TBC was to better target superannuation concessions thereby ensuring the system’s sustainability over time. The EM estimated the introduction of the TBC would affect less than one per cent of Australians with a superannuation interest. If this estimate is accurate, then arguably this particular calculation which is carried out on the full population (in retirement phase) represents a very inefficient and costly tax administration for what was meant to only have a one per cent application.

Design not hitting target

By its very nature, proportional indexation essentially rewards and benefits those who are able to defer the commencement of their retirement phase income stream to a later date. As a consequence, it may actually encourage those who are ready to retire (with amounts in excess of the General TBC) to defer and leave their superannuation balance in the accumulation phase until indexation does occur. Such behaviour would appear contrary to the intent and objective of proportional indexation.

Inconsistent treatment with other superannuation caps

The proportional indexation of the Personal TBC is unprecedented when compared with other indexation that takes place under the tax law. For instance, the Low Rate Cap Amount10 which represents a lifetime cap on the tax-free level of superannuation lump sums an individual can receive in their lifetime is indexed in line with AWOTE, in increments of $5,000. There is no proportional reduction based on how much of the previous Low Rate Cap Amount has remained unused.

Too many rates, caps and thresholds

It has taken industry participants and the ATO considerable time and effort to educate individuals on the concept of the TBA (including debits and credits) and the consequences of breaching their Personal TBC. At times, there has even been some confusion with the Total Superannuation Balance (TSB) which has also been pegged to the General TBC for the purposes of assessing eligibility to the following superannuation concessions:

- Non-concessional contributions caps (NCC) and associated bring forward caps;

- Government co-contributions;

- Tax offset for spouse contributions; and

- Segregated method to determine their earnings tax exemption (SMSFs and small APRA funds only).

We submit that there was a logical nexus and a familiarity developed with the $1.6 million between the General TBC and the TSB (at least for the above mentioned superannuation concessions). However, as proportional indexation comes into effect with an individual potentially having a Personal TBC not equalling the General TBC, The Tax Institute is concerned that the Personal TBC will further exacerbate what is becoming a very complex suite of rates, caps and thresholds operating within the superannuation system.

A lack of consistency has been applied historically across the various caps and eligibility criterion for superannuation concessions. Some caps are indexed based on either CPI or AWOTE whereas others are referenced to a specific date and/or data set.

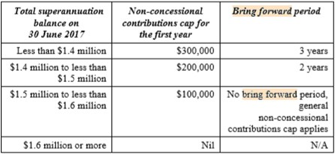

The non-concessional bring forward non-concessional contributions cap (that allows some individuals to use 3 years of the non-concessional contribution cap in a single year), provides an example of the anomalies apparent in the reference points for access to superannuation concessions.

The bring-forward non-concessional contributions cap is assessed based on an individual’s TSB, with thresholds referencing both the General TBC and the General NCC.

Source: Paragraph 5.47 of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 – Explanatory Memorandum.

Specifically, the references to $1.4 million, $1.5 million and $1.6 million reflect a calculation that takes a multiple of the NCC (originally set at $100,000) and subtracts it from the General TBC11.

Notably the table above gets very complicated and may produce anomalous eligibility thresholds given the indexation of the General TBC is based on CPI and the General NCC on AWOTE. This problem is further exacerbated if, in a given income year, the NCC is indexed but the General TBC is not (due to the higher $100,000 incremental hurdle).

Access difficulties to Personal TBC

Currently, financial planners and advisers have difficulties accessing clients’ TBA and TSB balances given the information is only accessible via the ATO and restricted to the individual and their tax agents.

Without this information, it is extremely difficult for advisers to provide appropriate financial advice which will not cause their clients to inadvertently breach their caps. Unfortunately, we foresee this problem only getting worse if and when proportional indexation comes into effect with an individual’s Personal TBC diverging from the General TBC12. This ultimately affects the quality of the advice provided and may lead to errors, giving rise to complaints and the need to remediate.

Reliance on ATO

Of particular concern is that the Personal TBC determination rests solely with the ATO, who in turn must rely on all Fund providers to report all relevant member’s transactions accurately and in a timely fashion. Any errors or omissions in the reporting may lead to subsequent re-reporting which may trigger a re-calculation of the Personal TBC. However, the individual and/or their financial adviser may have acted and relied upon the ATO’s calculation.

Notably in a recent AAT case13, a taxpayer submitted that they were led into error by misleading content on the ATO website when managing the excess over their Personal TBC. However, the Tribunal found in favour of the ATO and also confirmed that the Tribunal had no jurisdiction to address any application against the ATO even if its website could be said to be misleading This was the case, notwithstanding there was acknowledgement that the taxpayer had relied on the ATO information in good faith and made an honest mistake.

Furthermore, there appears to be no rights to object to any inadvertent breach of the individual’s Personal TBC in such a situation and is a real concern given the fact that the Commissioner does not explicitly have any discretionary powers to disregard an excess transfer balance (even if information obtained from the ATO contributed to the breach).

Culpability for errors or omissions unclear

As alluded to in the previous issue, it may also be unclear as to who is culpable for an inadvertent breach of the cap as a consequence of any error or omission in member reporting. With such a large superannuation system and the volume of transactions that occur, one can expect reporting errors

or omissions to arise from time to time that require re-reporting to the ATO. To the extent re-reporting causes a subsequent breach of the cap and/or denial of any related superannuation concessions, it is unclear who is culpable for that breach. This is particularly the case if the individual has multiple accounts with various Fund providers and there are errors or omissions experienced by more than one Fund provider.

Severe tax consequences for excess transfer balances not rectified

The breaching of the TBC may often lead to an individual disputing their excess transfer balance with the ATO and refusing to commute the excess. Individuals may give explicit instructions to their Fund not to process a commutation authority issued by the ATO. However, Trustees have no choice but to act and process a commutation authority that it receives14. Failure to do so within the prescribed 60 days will result in the income stream ceasing to be a retirement phase income stream15.

This in turn results in the income stream ceasing to qualify for the earnings tax exemption16 with the eligibility deemed to have been lost from the start of the income year in which the commutation authority was not complied with. Notably this tax outcome poses an administrative challenge particularly for large funds that operate retail Master Trusts and offer their members superannuation interests in unitised asset pools. Specifically, it becomes extremely difficult to even determine what portion of the income and gains from the unitised (pension) asset pools is attributable to that particular member. Furthermore, the Trustee would also need to assess the tax character of that income and gains, plus any applicable tax offsets in order to determine the effective earnings tax rate that ought to have been applied to the deemed assessable income.

More importantly, the Trustee’s compliance with a commutation authority may give rise to a complaint by the member for not complying with their explicit instruction or request not to process.

Outcomes and Conclusion

The current superannuation system is overly complex and costly to administer. There is merit in making it much simpler for all stakeholders.

The Tax Institute submits that simpler rules would assist in:

- Members and their advisers better understanding and managing the TBC; and

- Reducing the cost for both industry participants and the ATO to administer these rules.

The removal of proportional indexation specifically achieves both these objectives.

As with other existing superannuation caps, adopting the General TBC will ensure every individual has the same TBC regardless of when they entered the retirement phase. This will provide certainty to individuals and their advisers to better plan for their retirement, without having to rely on gaining access to ATO information.

The call for permanent relief for inadvertent and small breaches is aimed at red tape reduction and thereby increasing the overall efficiency of the superannuation system. At present, it can take up to 120 days before an excess transfer balance amount is withdrawn from retirement phase. Any such breaches tend to involve every party within the system and is therefore a very costly and time- consuming exercise. We submit this particular option strikes a good balance between maintaining the integrity and efficiency of the superannuation system. It should also obviate any breaches which may result from any misreporting and re-reporting of member transactions by Fund providers and reduce the number of disputes and complaints raised by the individual against the Trustee and/or the ATO.

Whilst the proportional indexation methodology is designed to target higher member balances, its universal application is more likely to impact superannuation funds with lower balance members. The Tax Institute considers it to be undesirable to significantly increase the complexity inherent in a system that has limited application against the object of the measure. There is still time to remove this provision from Division 294 before the first indexation event occurs and we urge the Government to carefully consider this submission.

____________________________________________________________________________________

1 Subsections 294-35(3) of the ITAA 1997.

2 Subsection 960-285(7) of the ITAA 1997.

3 Section 294-30 of the IT(TP) Act 1997

4 Subsections 294-35(3) of the ITAA 1997.

5 Subsection 960-285(7) of the ITAA 1997.

6 Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Act 2016 [No. 81 of 2016].

7 Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 – Explanatory Memorandum.

8 Unused cap percentage effectively is rounded up to the nearest per cent as a result of subsection 294-40(2)(c) of the ITAA 1997.

9 Paragraph 3.373 of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 – Explanatory Memorandum.

10 Section 307-345 of the ITAA 1997.

11 Subsections 292-85(2), (3), (4) and (5) of the ITAA 1997.

12 Indexation of the General TBC will first occur (in the following income year) if and when the December quarter CPI figure reaches 116.9.

13 Lacey and Commissioner of Taxation (Taxation) [2019] AATA 4246.

14 Section 136-80 in Schedule 1 to the TAA 1953.

15 Subsection 307-80(4) of the ITAA 1997.

16 Subdivision 295-F of the ITAA 1997.

Click here for The Tax Institute’s original submission published 28 Aug 2020 by THE TAX INSTITUTE

************************************************************

Commonwealth Budget 2020-2021 Superannuation Announcements

On 6 October 2020, Treasurer Josh Frydenberg delivered the Commonwealth 2020-2021 Budget.

For the superannuation announcements please click on the following links:

https://budget.gov.au/2020-21/content/factsheets/download/your_future_your_super_factsheet.pdf

https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-10/p2020-super_0.pdf

Superannuation at the crossroads

The Australian Business Review

16 september 2020

Glenda Korporaal

The super system is at a crossroads with the combination of the $33bn early access drain, the withdrawal of banks from wealth management and the decline of other traditional retail players in super.

When the history books are written about superannuation in Australia, one question to be asked is whether 2020 will be a high-water mark for the sector.

Overall, total new contributions going into super will continue to increase with the compulsory super contribution scheme, but the combination of the early access to super scheme, questions over the move to a 12 per cent compulsory guarantee levy and new fears that the October budget could allow more access to super for housing add up to an inflection point for the industry.

As Industry Super Australia chief executive Bernie Dean says, the worry is that having seen the success of the early access to super scheme since April this year, the government may be tempted to open up super for all sorts of short-term stimulatory means — sugar hits that limit the amount of money the government has to pay out of its own budget.

As AMP struggles and the banks exit the wealth management business and the private wealth management sector is still coping with the fallout from the royal commission, the traditional private sector companies and lobby groups that have championed the case are distracted or battling to get cut-through against rising anti-super voices.

Having to have two former prime ministers in Paul Keating and Kevin Rudd argue the case to continue the move to 12 per cent was a sign of the limited voices arguing in favour of the compulsory super system, which has been the envy of the world.

Until recently it appeared to have bipartisan support, introduced by Labor and supported by Liberal governments, but now that seems to be eroding.

There was a time when the total super asset pool continued to set records, going through the $1 trillion and $2 trillion figures barriers, underwriting a massive funds management industry in Australia and retirement savings-oriented businesses.

By the end of last year, the total assets in super hit $2.951 trillion, up from $2.88 trillion in June last year.

But the pendulum has swung back this year. Total assets in super funds at June were down to $2.864 trillion despite the sharemarket holding up well in the face of the pandemic.

The latest figures from the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority show that total contribution flows into super funds rose from $114.7bn for the year to June 30 last year to $120.6bn for the year to June 30 this year.

But total benefit payments — including those paid as a result of the early super release scheme that started on April 20 — rose from $76.5bn last financial year to a record $100.4bn for the financial year just ended.

This meant net contributions flows were down by an unheard of 38 per cent from $38bn to $23.5bn.

Total benefits paid out in the June quarter this year of $37bn were almost double the $21.1bn paid out in the March quarter and the $20.5bn in the June quarter last year.

The June quarter payouts included $18.1bn from the early release scheme with 2.4 million Australians choosing to draw on their super for an average amount of $7503.

Australian Prudential Regulation Authority data shows total drawdowns under the early release scheme are now $33bn, with more than 3.2 million Australians choosing to put their hands in their own retirement savings for an average payment of $7678. This means another $15bn flowed out of the system in the two months from July 1 to September 6.

Rather than falling, the average amount accessed by those going to the well a second time (allowed from July 1 until the end of the year) rose to $8427 compared with $7402 for the first application. In short, the super drain has continued with people who do access their super wanting to take out more.

No one can blame people doing it tough from wanting to access their super to pay short-term bills.

But the whole point of our super system is one of compulsory savings to provide income for retirement. The danger is that the government’s early access scheme opens a Pandora’s box of new reasons to access super that could, over time, undermine the system.

There have always been those who have been critical of compulsory super, introduced almost 30 years ago, for ideological reasons. The system, after all, was based on forcing workers who might not save to put money aside for their retirement.

The Treasury also has been wary of the total tax forgone in the super system. But the tax breaks are part of the quid pro quo of forcing people to lock up a proportion of their funds.

With some tweaks to cut back on concessions to the wealthy the system appeared to be holding up well, generating a huge pool of national savings that was being used to help stabilise our financial system in times of crisis and invest in infrastructure and key assets such as electricity, ports and airports.

Now the concern is that the debate has reached a tipping point and super is regarded as a honey pot to be raided.

There is no magic pudding. The less put away for retirement, the worse off people — particularly lower-paid people — will be when they stop working. The value of compounding means that $20,000 taken out of super has a net cost of many times that at the end of a 30-year career.

Another factor is that the system has allowed the rise of a new section of the financial system — the $700bn industry super sector — while the retail super sector has been hit by the royal commission and other issues.

The Jetstar of the super sector, industry super funds have not had to deal with the legacy issues of the private sector super funds, having lower cost structures and a younger membership base as well as not having to pay out profits to shareholders. Their strong cashflows also have allowed them to deliver good returns as they could safely lock in their investments over a longer timeframe.

But there is no great love for the industry super fund sector in some conservative parts of politics despite the fact, by and large, they have delivered well for their millions of members.

The super system is at a crossroads with the combination of the $33bn early access drain, the withdrawal of banks from wealth management and the decline of other traditional retail players in super.

GLENDA KORPORAAL

ASSOCIATE EDITOR (BUSINESS)

Political rivals gear up for a super stoush

29 August 2020

Dennis Shanahan – Political Editor

Scott Morrison and Anthony Albanese have identified two policy and political issues — superannuation and aged care — that have fresh currency and urgency as a result of COVID-19. They could have as much impact electorally as the handling the coronavirus virus itself.

The competence demonstrated in dealing with the health threat and, perhaps more important, the economic recovery is dominating the national agenda and will do so during the federal election, which could be held late next year.

But the confronting and transformative impact of the coronavirus on administration and public attitudes has changed the nature of fundamental issues that existed before the pandemic.

The Prime Minister can see the potential damage to his standing and the credibility of the Coalition created by the disastrous death rate in aged-care homes as a result of Victoria’s wave of new cases. There have been more than 340 deaths in care.

The Opposition Leader sees aged care as a pivotal point politically. He is single-mindedly pursuing Morrison for being responsible as the commonwealth leader, arguing the Prime Minister has been too slow to respond to earlier warnings and even has been heartless by pointing to 97 per cent of aged-care homes in Australia (more than 90 per cent in Victoria) being COVID-free.

But even Albanese sees the importance of changes to superannuation rules and regulations beyond the pandemic. In a national speech on Thursday about aged care that prosecuted a case of “neglect”against Morrison before, during and after the coronavirus outbreak, the only other issue Albanese raised was superannuation.

The Opposition Leader said it was “sneaky and wicked” of Morrison to allow early access to superannuation funds for workers affected by coronavirus because those with the lowest funds — women and young people — were taking out the most. He said 600,000 accounts had been reduced to zero.

“What’s happening right now is casting a shadow so long it will darken future generations,” Albanese said.

“It will increasingly fall to them to prop up budget spending ever more on aged care and pensions. This means either that future workers will face higher taxation or that future government services — including the Age Pension — will come under pressure.”

He defended Labor’s legacy of compulsory superannuation payments, saying: “Universal superannuation was built to avoid this problem. It was never designed to be a mere safety net.”

Yet Morrison detects a public attitudinal change towards compulsory superannuation payments and preserving super savings, where there was once an almost monolithic acceptance of untouchable superannuation and the aim of self-reliance for retirees through compulsory super.

Like the brutal reality of deaths in aged-care homes, the surprise emergency access to superannuation funds to help those who have lost jobs has struck a deep chord in the public that will colour future political decisions.

Almost by accident Morrison discovered a deep change in attitude when speaking on radio about the early access to superannuation and used the line that “it’s the people’s money, not the fund managers”.

The prime ministerial switchboard lit up strongly enough to supplant the prime ministerial Christmas tree, and a visceral reaction confirmed what the figures were telling the Coalition.

As of this week more than 2.8 million Australians had withdrawn superannuation savings of $34bn early, and the bulk of applicants were low-income earners, essentially women and young people, who preferred to take what they had on hand rather than wait for decades and face the loss of funds through fees.

The reaction, double the Treasury estimate, was testament to a pent-up demand from the public to access their superannuation. It was a signal to Morrison and Albanese that a previously almost unassailable Labor stranglehold on superannuation policy and co-operation with industry super funds within the public and the Senate had been weakened.

The emergency superannuation access powers have broken the banks’ super debate, and a politically and ideologically frustrated Coalition is moving to take advantage.

Apart from a number of legislative victories in the Senate on superannuation and plans for more changes to come there is also the broad question of whether the 0.5 per cent increase in the superannuation guarantee contribution legislated to take effect from July 1 next year will go ahead as promised.

There is enormous pressure from within the Coalition, employers and business to freeze the contribution at the current 9.5 per cent in the name of helping economic recovery and putting money in workers’ pockets.

Using the early access issue, Morrison is building a campaign that it’s better for workers to control their money and that industry superannuation funds aligned with unions and Labor are “misusing” fund members’ money for ends outside their responsibility to provide returns to workers.

After the passage of legislation in the Senate to allow more choice for workers on which fund they use, Morrison told parliament: “It’s important legislation which understands that people’s superannuation money is their money — not the Labor Party’s, not the industry fund manager’s, not any fund manager’s.

“We believe it belongs to them because they worked for it, they earned it, they saved it. And when they need it in a time of pandemic we’re going to make sure they can get access to it.”

Morrison claimed Labor MPs were “like puppets on a string on behalf of the union fund managers and they trot out the lines on their behalf. But we have a message for them: it’s not your money. We won’t let you take it from those who’ve earned it when they need it.”

Greg Combet, chairman of Industry Super Australia and a former minister in the Rudd and Gillard Labor governments, told Inquirer that early access for everyone to their superannuation savings for any purpose before their retirement “would be a disaster”.

He also said any backtracking from the legislated rise in the super guarantee would be a “breach of faith”.

“The rise in the superannuation guarantee was an election promise which has been reconfirmed multiple times by the Prime Minister, and it has been legislated by the parliament,” he said. “It would be against the interest of superannuation fund members and as a consequence the industry super funds would oppose such a move by the government.”

He also agreed with Albanese and prepared for a real battle ahead by declaring “ordinary Australians … will have to work years longer to achieve the same level of superannuation savings. Taxes would also need to be higher in order to meet increased demands on the pension.

“The 0.5 per cent increase in the superannuation guarantee due in July next year would only equate to about a $5 per week increase in contributions for a person on $50,000 per year. This is affordable.

“Anyone with any knowledge of the real world knows that if the super guarantee rise does not go ahead, there will be no compensating wage increase. All that will happen is that people get no wage increase and no super.”

Albanese accused the Coalition of “setting us up for a future where millions of Australians are condemned to a very lean retirement”.

“The Liberal Party’s ideological prejudice means they certainly don’t want workers to have self-sufficiency in capital and have undermined superannuation at every opportunity,” he said.

But Morrison and Josh Frydenberg sense a change in the public attitude and can point to seven separate pieces of superannuation legislation passed recently directed at loosening the union and Labor grip on the resources and influence of the industry super funds.

In the lead-up to the seminal debate next year on the rise in the compulsory super contribution there will be more superannuation debates, including the Coalition’s claim that millions of dollars of members’ funds are being “misused” in payments to unions as “sponsored organisations” and marketing and entertainment.

It’s all part of long debate in a changed atmosphere that will be as important as aged care and the pandemic recovery.

Superannuation must be built on reality, not stereotypes

The Australian

29 August 2020

Adam Creighton – Economics Editor

The biggest policy battleground over the next year will almost certainly be superannuation.

The government is sitting on the retirement income review, a recommendation of the Productivity Commission from 2018 that is bound to raise troubling questions for the super sector.

Aware of the political risks of tinkering with super, the government instructed the panel not to make specific recommendations, but the facts alone should make it obvious what needs to be done.

The review will probably show, just as the Henry tax review did a decade ago, that lifting the superannuation guarantee to 12 per cent, as is currently legislated, will cost far more in fees and forgone tax revenue than it could ever save in age pension outlays.

Fees are about $30bn a year, concessions are about $36bn, while age pension savings are, very generously, less than $10bn a year.

Proceeding with a policy that’s a net drain on public finances, especially when budget deficits and debt have ballooned, is questionable. The review will also make it clear mandatory super contributions are paid by workers, out of their gross incomes, rather than by employers. The genius of Paul Keating’s innovation, compulsory super, is that it appears to workers as if contributions are made by their employers.

But the economic incidence is very different from the legal incidence. Employers pay workers’ income tax, on their behalf, yet few believe an increase in income tax would be borne by the boss.

From the employer’s point of view, employees’ income tax and superannuation contributions are the same. The government says what proportion of workers’ pay goes in tax, super and disposable income.

In the short term an employer might choose to absorb an increase in the compulsory savings rate, but in the long run the government cannot dictate how much a business will spend on payroll. It must by definition mean lower take-home pay for workers.

Absent these two arguments, the super industry is likely to fall back on a paternalistic one: people don’t save enough without compulsion. While savings myopia might feel right, it’s empirically wrong. People are simply not spending their accumulated savings in retirement and instead are leaving significant bequests, research shows.

To be sure, uncertainty about how long we will live naturally induces precautionary saving, although this becomes less and less a justification the older we become (and the probability of dying increases).

A major study of 10,000 age pensioners in 2017 found that at death the median pensioner still had 90 per cent of their wealth compared to the start of their retirement. “On average, age pensioners preserve financial and residential wealth and leave substantial bequests,” the authors concluded.

We are hardwired, whether for cultural or biological reasons, to protect or grow our wealth. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it does undermine the claim that people aren’t saving enough. On the contrary they might be saving too much.

Grattan Institute analysis of the Survey of Income and Housing conducted by the ABS similarly found retirees typically maintained or increased their non-housing wealth through their retirement.

“Wealth appears to have dipped only because the global financial crisis reduced capital values, rather than because retirees drew down on their savings,” says Grattan.

“The bottom third by wealth of the cohort born in 1930-34 (aged 71-75 in 2005) increased their non-housing wealth from $68,000 in 2005 to $122,000 in 2015,” the authors pointed out.

The government has known this tendency for some time, too. As social security minister in 2015, Scott Morrison pointed to research by his own department that showed 43 per cent of pensioners increased their asset holdings during the last five years of life, and a quarter maintained them at the same level. “Less than a third of pensioners actually saw their assets decrease in their last five years,” he said.

What is the point of providing concessions if the savings are not being used to fund retirement but are simply passed on? It would be better to scrap the concessions, pay a bit more in age pension, and use the difference to radically cut income tax rates for everyone.

While the Coalition government is unlikely to propose anything like that, there’s an argument for being bold. The fact around three million Australians have just accessed their superannuation is a massive chink in the armour of compulsory super.

The government could make super voluntary, in effect offering a significant pay rise to any worker who wanted it. Remember, employers don’t care whether workers’ pay is sent to a super fund or the worker’s bank account.

The savings could be used to make significant cuts to income tax, or make the age pension universal, thereby scrapping the means testing that has so twisted the incentives of the over 65s. About 80 per cent of retirees already receive the full or part age pension. A universal pension would remove the significant disincentives to work that pensioners face, dramatically simplify retirement and end the game of retirees’ engineering, quite understandably, their affairs in order to receive a part-pension.

There are powerful political reasons for being bold, too.

Labor will be hoping the government does seek to delay or stop the increase in the super guarantee. That would give the party, rendered irrelevant by the coronavirus, something to fight for, even if it were for the vested interest of the super industry rather than working people. Indeed, a senior Liberal once told me the biggest supporters of compulsory super were older, wealthy Liberal voters, who believed the poor should be forced to save for their retirement so as not to be a burden. The median worker, let alone the poor, can never save enough to provide the equivalent of an age pension.

Regardless, facing a hysterical campaign from Labor and the doubts among its own base, it could lose the debate.

The government needs a positive plan rather than promising to stop something from occurring. Dangling the carrot of an optional near 10 per cent pay rise for workers or promising a universal age pension would be a significant proposal with plenty of merit.

The government’s successful early access scheme, which has seen around three million people withdraw almost $40bn, has delivered a body blow to compulsory super. Now is the time to reform it.

Super increase in doubt as Scott Morrison fears hit to jobs

15 August 2020

Olivia Caisley – Reporter

Patrick Commins – Economics Reporter

Additional Reporting: Joe Kelly

Scott Morrison has given a strong signal he is no longer wedded to increasing the super guarantee to 12 per cent, acknowledging it could suppress wages and potentially cost jobs, as the government weighs up the findings of an independent review into retirement incomes

The Prime Minister on Friday noted the coronavirus pandemic was a “rather significant event” which had occurred since he pledged at the last election to continue with the scheduled increase in the super guarantee, due to reach 12 per cent by 2025.

On Friday, Reserve Bank governor Philip Lowe warned that increasing the super guarantee would “certainly have a negative effect on wages growth” and that, if it went ahead, he would “expect wages growth to be even lower than it otherwise would be”.

Dr Lowe argued there could be flow-on effects if the guarantee was increased, telling the standing committee on economics it might reduce take-home pay, cut spending and potentially cost jobs.

Mr Morrison later said he was “very aware” of the issues raised by Dr Lowe and argued they should be “considered in the balance of all the other things the government is doing”.

The warning from Dr Lowe came as an inquiry heard that nearly three million Australians had applied for early access to their superannuation, with $33.3bn already approved. Labor has accused the government of undermining the superannuation system through the early access program, with Anthony Albanese warning that too many young Australians had exhausted their super balances.

Dr Lowe also criticised the states for not carrying their “fair share” of the fiscal burden, saying they were preoccupied with their credit ratings rather than job creation. He repeated the RBA’s baseline forecasts for the unemployment rate to reach 10 per cent by the end of the year and expected the jobless gauge to “still be around 7 per cent in a few years’ time”.

“The challenge we face is to create jobs, and the state governments do control many of the levers here,” he said.

Mr Morrison seized on the call to say the federal government had done the “seriously heavy lifting” to navigate the pandemic and urged state and territory leaders to “provide further fiscal support”. He said the states had provided “about $45bn in both balance sheet and direct fiscal support” but the federal government had provided “about $316bn”.

Dr Lowe said that, with the cash rate at a record low of 0.25 per cent, further monetary policy easing was unlikely to gain any traction in stimulating demand. Instead, fiscal policy and structural reform would be the primary tools to carry the country through the crisis and lay the foundations for recovery.

He identified measures such as removing stamp duties — which he called a “tax on mobility” — and industrial relations reform, echoing calls from the Productivity Commission this week.

“There’s a process going on at the moment to try and make the enterprise bargaining system more flexible, so we can get back to a world where businesses and employees can get together and make their businesses work effectively, rather than be weighed down by process,” he said.

Dr Lowe warned Australians to be prepared for a “bumpy and uneven” recovery, and argued the second wave of coronavirus infections and new restrictions meant the bank was “not expecting a lift in economic growth until the December quarter”.

The early release of superannuation: the financial consequences

16 August 2020

Jim Bonham https://SaveOurSuper.org.au

Early release of superannuation

Limited early release of superannuation has been a part of the government’s support to people suffering financial stress caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. This has been welcomed by some but strongly opposed by others because it is seen as a corruption of compulsory saving and disruptive to super funds.

The financial implications

This paper takes a quantitative look at the financial implications of a $10k early release, for three hypothetical individuals Continue reading

Boomer incomes fall as younger generations enjoy benefits surge

The Weekend Australian

1-2 August 2020

Patrick Commins – Economics Correspondent

Baby boomers are alone among the generations to suffer a fall in income through the COVID-19 crisis, according to Commonwealth Bank analysis of three million households who bank with the lender.

The unprecedented level of government support in response to COVID-19 and the massive take-up of the early access to super schemes boosted average household income overall by 4.2 per cent over the year to the June quarter, the research shows.

Salary income dropped 6.6 per cent on average as the health crisis put hundreds of thousands of Australians out of work. But a 54 per cent surge in average incomes from government benefits versus a year earlier, and a 64 per cent jump in “investment income” — which captures payments from the first withdrawal of up to $10,000 from super under the special early-release scheme — has led to what CBA senior economist Kristina Clifton called a “positive income shock”.

Still, spending was down close to 9 per cent in the June quarter from a year before as households hunkered down amid the first recession in close to three decades.

“We can see that on average people are saving a lot of money at the moment,” Ms Clifton said.

While the average income among the three million households has climbed, a breakdown by generation reveals that boomer households have on average experienced a 1.4 per cent drop. Meanwhile, the two youngest cohorts — Generation Z and millennials — enjoyed the biggest increases, at 8.9 per cent and 6.7 per cent respectively. The average income among Generation X households climbed 3.2 per cent over the year to the June quarter, while older Australians had an increase of 2.8 per cent.

Ms Clifton said boomers had not received as much of the emergency government support packages. Nor had they made as much use of the special rules allowing early access to their retirement savings.

The bank’s data showed a 50 per cent average surge in government benefits across households, but boomers had received a comparatively lower 24 per cent boost. The three younger generations received in the order of 40 per cent more from the government in over the three months to June versus the same period a year before.

And while the overall average household’s level of spending fell substantially from last year to this, Gen Z spent nearly 4 per cent more, and millennials an extra 1 per cent. Last week Treasury released figures suggesting part-time and casual workers on the $1500 JobKeeper payment were being paid in aggregate $6bn more than they were earning before the crisis.

SMSF cost estimates ‘stale’, says ASIC as it starts review

The Australian Business Review

15 July 2020

James Kirby – Wealth Editor

The market regulator is set to dump highly controversial estimates that suggested self-managed super funds cost more than $13,000 a year to run and need 100 hours annually to manage.

ASIC chair James Shipton told a Senate committee on Wednesday the estimates were “stale” and the regulator was now actively reviewing the figures that have caused consternation across the SMSF industry.

The controversial claims first surfaced in an ASIC Fact Sheet last year designed to inform investors if SMSFs were suitable to their needs.

ASIC commissioner Danielle Press said the Fact Sheet was no longer being distributed by the regulator. The numbers, which are at least three times higher than many in the industry estimate, are still on display at ASIC’s Moneysmart website.

The move to review the figures comes after the ATO, which is the specific regulator for SMSFs, recently published statistics showing the operational expenses in SMSFs were at a median of $3923.

Aaron Dunn of Smarter SMSF has called the ASCI figures “grossly incorrect”.

Dunn suggests operating expenses for the vast majority of SMSFs are less than 1 per cent of total assets.

Ron Lesh, managing director of SMSF software administration provider BGL, branded ASIC’s estimate of $13,900 to run a fund and 100 hours to manage as “a manipulation of data”. Lesh told The Australian the number of hours it would take per year to run a fund was about 30.

The ASIC executives were responding to questions put forward by Jason Falinski, the Liberal member for Mackellar, NSW at a parliamentary joint committee on Corporations and Financial Services.

Though ASIC has been praised for efforts to protect consumers, especially in the area of property development where “off the plan” projects can prey on inexperienced retiree investors, the regulator has regularly sparked antagonism in the SMSF sector, which has more than a million members.

The true cost of running a DIY fund remains a contentious issue as bigger industry and retail funds continue to protect their industries from leakage to independent superannuation. But SMSF commencements have recently enjoyed a rebound.

Industry analysts suggest the ASIC figures were high because it used averages, which meant the complete outliers such as super funds that had tens of millions of dollars under management were included — the median funds under management for SMSFs in Australia is closer to $700,000.

ASIC’s high estimates would also appear to include costs such as insurance and financial advice, which are associated with running an investment portfolio but not in running an SMSF, which is simply a tax vehicle for private superannuation.

The regulator continues to state in its documentation that “on average, an SMSF will not perform as well as a professionally managed super fund” — a claim hotly debated among SMSF operators who explain it is impossible to determine generic figures for performance from the highly disparate population of SMSFs in the sector.

The regulator also tells investors inquiring about setting up funds “the returns you can expect from your disparate SMSF are determined by your balance”.

If your balance is more than $500,000, it is possible you might get returns that are competitive with APRA-regulated funds.