The Australian

25 July 2017

Judith Sloan

It won’t surprise anyone that I don’t regard myself as a victim — never have, never will. Can I also point out that one of the greatest

joys of my life has been bringing up children? I was lucky to be able to drive a balance between family and work.

So when I read the latest treatise bemoaning the shabby treatment of women in the workforce, I am generally uninclined to accept

the message or the recommendations at face value.

The recent topic has been superannuation and women. A study was conducted by think tank Per Capita and was funded by the

Australian Services Union. Note that the motto of Per Capita is Fighting Inequality in Australia. You get the drift.

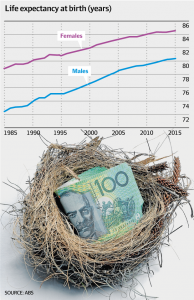

It turns out that women’s superannuation balances are systematically lower than men’s, that the gap increases across the course of

working lives and that, at the age of 65, the average difference between men’s and women’s superannuation accounts is $70,000.

The median women’s balance immediately before retirement is less than $80,000. Mind you, the median men’s balance is only

$150,000. Anyone with these sorts of balances, and assuming a lack of other substantial assets (apart perhaps from a home), will

qualify for the full age pension and its associated benefits.

The authors of the study incorrectly describe the state of women’s superannuation as a wicked problem. A wicked problem is one

with inconsistent objectives and a lack of agreed information. This is simply not the case when it comes to women and

superannuation.

If there is a problem, it is the broader one related to the real purpose of compulsory superannuation. And this applies to both women

and men. For anyone on relatively low wages, all superannuation does is force them to accept reduced wages during their working

lives in exchange for possibly knocking off their full entitlement to the age pension. It’s a very bad deal.

Year after year these workers must forgo current consumption, which may now include buying a house but also help with the costs

of rearing children, meeting daily expenses and the occasional holiday, to be slightly better off when they retire. It really is a diabolic

trade-off for these workers, but from which they cannot escape.

So let’s return to the study. The reasons for women’s lower superannuation balances are obvious: on average, they earn less during

their working lives and they work less. This doesn’t mean that all women have low superannuation balances, just as this doesn’t

mean that all men have high superannuation balances.

Let’s take the working less bit first. Women are much likelier to work part time than men. In the most recent figures, women make

up 47 per cent of the workforce, a historical high. But almost half of women work part time, defined as those working 35 hours a

week or less, while only 18 per cent of men work part time.

Note, however, that the proportion of men who work part time has also been rising.

On this basis, it is hardly surprising that women’s superannuation balances are lower. They work fewer hours than men and hence

the wage on which their superannuation contribution (currently 9.5 per cent) is based is also lower.

But we shouldn’t forget that most women who work part time are doing so to balance their family and work responsibilities. And

many of these women quite rightly regard earnings and superannuation as a joint family product with both partners contributing to

the common pool.

It also should be noted that in the event of divorce, superannuation is regarded as an asset of the marriage to be divided up as part of

the financial settlement.

So what is the impact of the gender pay gap, an issue that attracts a lot of attention, most of it ill-informed?

At present, the difference between male and female earnings is about 16 per cent. It has fallen slightly as the mining investment

boom has come off and men have lost their high-paid jobs in that sector.

But the gross pay gap doesn’t tell us much about the explanations. After controlling for the many variables that affect earnings, such

as occupation, education, training, job tenure and the like, the pay gap narrows significantly, although it doesn’t reduce to zero.

But here’s the rub, at least for the Per Capita study and its sponsor, the Australian Services Union: the gender pay gap for low-paid

workers is explained entirely by wage-related characteristics. Moreover, the impact of minimum wages is to increase women’s

earnings relative to men’s.

So what should you make of the recommendations of this dubious study? In a word, they are ridiculous.

Let’s take the last one first — that the superannuation contribution be lifted immediately to 12 per cent. What the authors are saying

is that all workers must immediately forgo an additional 2.5 percentage points of their wage to augment their final superannuation

balance in several decades.

Then there are all sorts of silly suggestions for fleecing taxpayers some more to top up the superannuation balances that the authors

regard as inadequate.

But this makes no sense at all. After all, these low super balance workers will qualify for the full age pension, which in turn is fully

funded by taxpayers.

Why ask taxpayers to pay now when they will be forced to pay later?

Then there is the typical recommendation of these types of reports — add another government agency to the very long list of existing

agencies. In this case, the re-establishment of the largely pointless Office of the Status of Women is the suggestion.

For heaven’s sake, we already have the efficiency-sapping and senseless Workplace Gender Equality Agency whose work is of such

a poor standard that no one takes it seriously. But it doesn’t stop the agency from imposing more demands for information on

businesses every year.

In point of fact, there is a big issue here: what really is the justification for the system of compulsory superannuation? The central

rationale for superannuation was that it would replace the Age Pension and give workers a more comfortable retirement than might

have been the case.

Given the forecasts of the proportion of workers who will break free from the Age Pension during the next 40 years — it hardly

budges — the debate we should be having is whether we should ditch compulsory superannuation altogether.