by Jack Hammond and Terrence O’Brien

Note: SuperGuide has invited advocacy group, Save Our Super, to highlight the immediate and long-term implications of the federal government’s latest changes to super and the Age Pension. The authors of this article, Jack Hammond QC, founder of Save Our Super, and Terrence (Terry) O’Brien, a retired Treasury official, have kindly shared their decades of combined expertise and experience in the legal, economic and policy areas. This article is based on a longer paper produced by Save Our Super, and the link to the Save Our Super website, and to the longer paper appears at the end of this article. For information on the specific super and Age Pension changes, see list of articles at end of this article.

Progress, far from consisting in change, depends on retentiveness. ….. when experience is not retained, as among savages, infancy is perpetual. (Georges Santayana, The Life of Reason, Volume 1, 1905)

The end of a decade

To build personal savings to a level that would support a self-financed retirement takes a working lifetime. Regrettably, the Coalition government has given Australia’s most comprehensive retirement income reforms just 10 years before reversing them.

In 2007 a former Coalition government enacted the well-researched Simplified Superannuation reforms to improve retirement living standards, which was based on two central ideas: the introduction of tax-free super for most over-60s and a gentler taper rate on the Age Pension assets test.

In changes taking effect in 2017, the current Coalition government completely reversed policy direction on the two central ideas of the 2007 reforms.

Background on the 2007 reforms: Simplified Superannuation contained a series of radical Age Pension and superannuation reforms proposed in the May 2006 Budget, and detailed in an extensive discussion paper of the same name, open to consultation until August 2006. The reforms were legislated in slightly modified form and took effect mostly from 1 July 2007 (for superannuation) and 20 September 2007 (for the Age Pension). The full account is conveniently available at http://simplersuper.treasury.gov.au/documents/ . The package is sometimes referred to in later documentation as the ‘Better Super Reforms’.

The reasons for the 2007 changes, the impacts of the poorly-tested 2017 changes, and the implications for the future of Australian retirement income policy are developed in a longer paper from which this summary is drawn. That paper is available on the Save Our Super website (see link at end of this article).

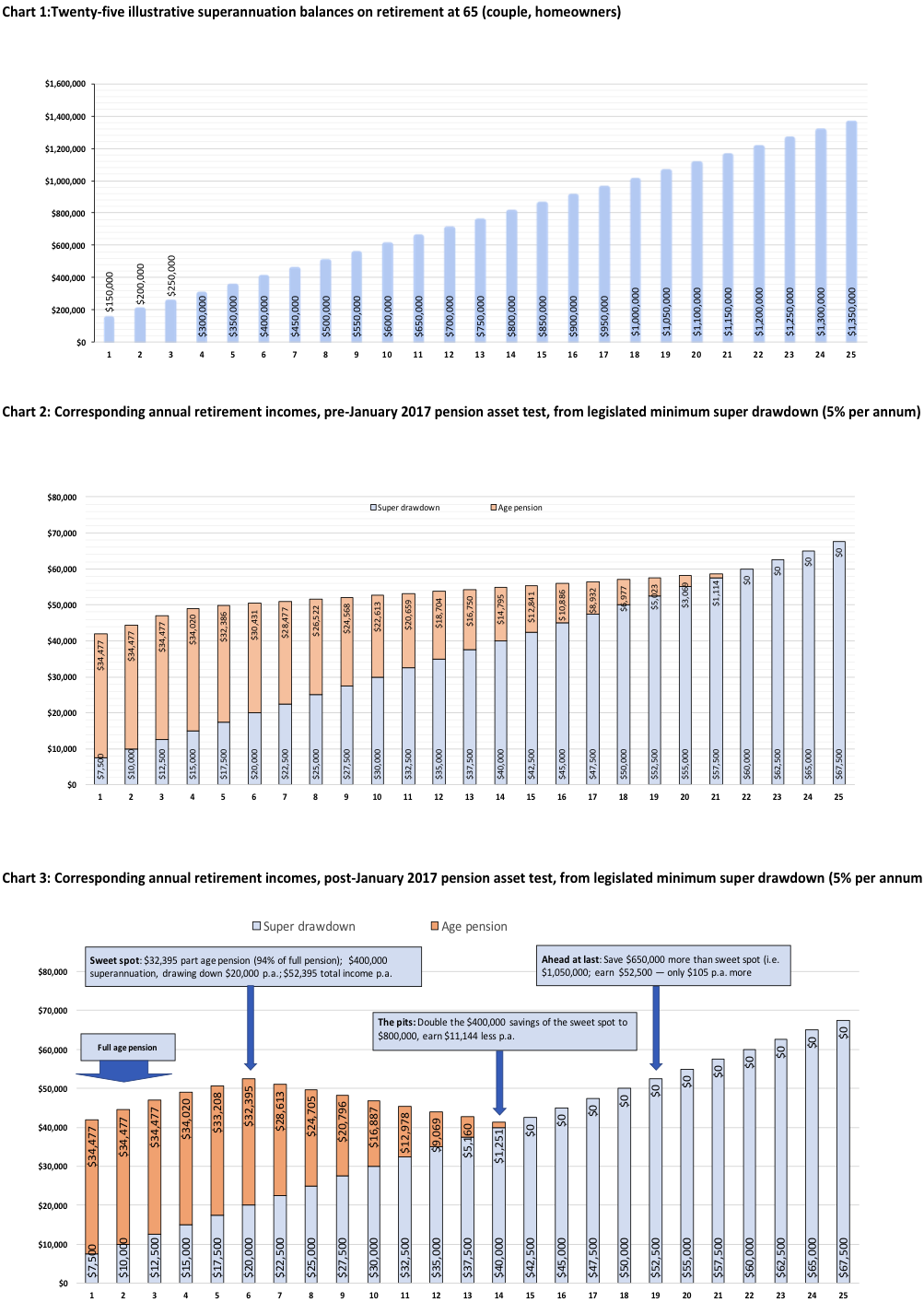

The 2015 and 2016 Budgets separately (and perhaps accidentally) created, from 2017 onwards, incentives for a retirement strategy of maximising income by accessing a substantial Age Pension, supplemented by moderate superannuation savings. In the example we illustrate here, for a couple with their own home, lifetime savings should logically be self-limited to about $400,000 to maximise total income sourced from Age Pension entitlements and superannuation savings. The situation is illustrated in the charts below.

Locking in a high Age Pension

Oddly, the optimum use of the Age Pension suggested by the Coalition government’s incentives will tend to drive people towards accessing about 94% of the full Age Pension. This tendency is signalled principally by ‘taxing’ superannuation income from savings between $400,000 and $800,000 at an effective marginal tax rate of over 150%. This financial impact results from doubling, in January 2017, the withdrawal rate in the Age Pension assets test back to its pre-2007 level (from losing $1.50 of Age Pension for every $1,000 of additional savings over the assets-free area, to losing $3.00 of Age Pension for every $1,000 of additional savings). Over the savings range of $400,000 to $800,000, doubling lifetime savings leads to about $11,000 less overall annual income. This is the same issue first reported (with slightly different estimates) by Tony Negline in ‘ Saving or slaving: find the sweet spot for super’, The Australian, 4 October 2016, and ‘Save more, get less: how the new super system discriminates’, The Australian, 26 November 2016.

Caught in a pincer movement

Only when superannuation savings rise to $1,050,000 is it possible to enjoy more income in retirement than from saving $400,000 and taking 94% of the full Age Pension.

Further, key July 2017 superannuation changes — the unprecedented $1.6 million transfer balance cap, and the reductions in allowable concessional and non-concessional contributions — make it much harder to ‘save across’ the savings trap between $400,000 and $1,050,000. From 1 July 2017, would-be self-funded retirees have been caught in a pincer movement between the Age Pension changes and the superannuation changes. Those with super balances already in the ‘savings trap’ between $400,000 and $1,050,000 are, in effect, encouraged to spend the excess over $400,000 (for example on holidays, a more valuable house, or renovations) at no cost to their annual income. Instead, increased and sustained reliance on the Age Pension will make up the shortfall in superannuation income, and limit if not reverse the assumed short-term expenditure savings for the Coalition government.

Retirement income policy demands long-term modelling

Whatever the short-term budget impacts, it is the long-term effects of these changed incentives on savings and work over a career spanning 40 or more years, and on pension dependence over a retirement spanning 30 or more years, that are the most important.

The long-term effects of the 2017 super and Age Pension changes alter retirement living standards and fiscal sustainability through their effects on superannuation saving, workforce participation, retirement decisions and Age Pension uptake.

For the 2007 reforms, Treasury’s special retirement income modelling group published a series of estimates (both at the time, and subsequently) of the long-term evolution of retirement living standards and superannuation and Age Pension usage using RIMGROUP, a comprehensive cohort projection model of the Australian population. Regrettably, there is no publicly available, official modelling of the 2017 system with the sufficiently long, 40-year horizon necessary to clarify whether the new system improves retirement living standards and fiscal sustainability or (as we argue) will very likely worsen them.

The likely halt in declining dependence on the full Age Pension

Even without the necessary long-term modelling, it is clear that the rapid move that was underway from reliance by most on a full Age Pension towards supplementing a diminishing part Age Pension with increasing superannuation savings will now be greatly slowed or halted.

The destruction of confidence in retirement income policy making

Moreover, the Coalition government’s reversal of its own 2007 policies in just a decade (and without enacting appropriate grandfathering provisions relating to the previous rules) has seriously damaged confidence in both superannuation, as a repository for life savings, and in the Age Pension, as the safety net for those less able to save (for the authors’ analysis of why grandfathering is so important, see SuperGuide article, https://www.superguide.com.au/the-soapbox/super-changes-grandfathering-rules ).

We argue that the incoherence and perverse incentives now at the heart of retirement income policy presage the need for further policy changes. The Age Pension and superannuation policies are now Budget-to-Budget propositions.

Overloading a sinking ship

Another consequence is that the ambitions of the Coalition government to load new tasks on to superannuation incentives, such as creating deferred income products or assisting saving for a first home, are likely to fail.

If citizens can’t rely on the government to respect obligations to those who trusted their lifetime savings or retirement income to yesterday’s laws, why should they allocate additional savings for a decade or more hence on the basis of today’s laws?

The 2016 Federal election saw Labor, Liberals and the Greens in a chaotic, ill-specified competition to raise more tax from superannuation, with no modelling of the long-term effects. Such a chaotic approach does not augur well for future policy making in this most complex policy area, where mistakes have long-lasting consequences and savers’ confidence is easily destroyed and very difficult to rebuild.

Pictures of policy reversal: the 2017 savings trap

The three charts below show how the Age Pension changes in the 2015 Budget (taking effect from January 2017) could be claimed by the government to save expenditure in the short run. But coupled with the superannuation changes in the 2016 Budget (taking effect from July 2017), they introduce instability and create long-term Budget costs that will likely render the changes unsustainable. The charts below are derived from a model created by Sean Corbett, B Comm (UQ), B A (Hons) in Economics (Cambridge), M A (Cambridge). Sean has more than 20 years of experience in the Australian superannuation industry, principally in the areas of product management and product development. He has worked at Challenger and Colonial Life, Connelly Temple (the second provider of allocated pensions in Australia) and Oasis Asset Management.

The Corbett model captures the key interactions between the superannuation system and the Age Pension under its income and assets tests. It uses illustrative superannuation balances rising in $50,000 increments, and allows exploration of total incomes enjoyed with various superannuation balances by retirees who are either single or part of a couple, either with or without home ownership. It also allows estimates how long various superannuation balances will last in retirement. The Corbett model is archived and available on request from the authors, who thank Sean for his permission to draw on his work, and for his helpful comments on drafts of the longer paper cited above. Assumptions behind the model and the charts drawn from it are available in our longer paper (see link at the end of this article).

Chart 1 below shows illustrative superannuation saving totals in 25 steps between $150,000 and $1,350,000 for a 65 year old couple who own their home. Charts 2 and 3 show the Age Pension available, the legislated minimum superannuation income drawdown and the total income corresponding to each of the 25 illustrative lifetime superannuation total balances appearing in Chart 1. Chart 2 shows the situation under the rules that applied from 2007 to 2016; while Chart 3 shows the situation under the Age Pension rules since 1 January 2017 and the superannuation rules after 1 July 2017. To focus comparison on the change in policy itself (rather than indexed changes in pension rates), both charts use pension values at September 2016. Further analysis follows the charts below.

Is a steeper taper rate for the Age Pension assets test ‘fair’?

The potential short-run expenditure savings from reverting to the pre-2007 Age Pension assets test taper rate (losing $3 of Age Pension for every $1,000 of savings) can be seen by comparing Chart 2 and Chart 3: Couples in cases 15 to 21 lose all part Age Pension entitlements under the 2017 Age Pension changes.

Whether the potential short-term savings from introducing a harsher Age Pension assets test will eventuate is uncertain — it depends on behavioural responses to perverse incentives outlined below. The new 2017 rule has been defended as ‘fair’: why should a couple owning their own home and with $850,000 (case 15) or more in superannuation receive any part Age Pension, however small?

In 2006 and 2007 the answer to that question was explained in Simplified Superannuation and is illustrated in Chart 3. To truncate the part Age Pension abruptly by case 14 produces a wide range of very high marginal effective tax rates of over 150%. This causes its own unfairness: as noted above, a couple could double their lifetime superannuation savings to $800,000 over the ‘sweet spot’ of $400,000, yet would have an annual retirement income of $11,000 less. A couple could save $650,000 more than the superannuation ‘sweet spot’ and get barely any more annual income. We suggest few would consider those fair outcomes.

Dissipating savings in the short run; limiting saving in the long run.

In the short run, those with superannuation savings already above the ‘sweet spot’ will be induced to spend those savings, increasing the part Age Pension they can claim. Over time, this savings trap is likely to produce a heavy focus on ‘Age Pension first’ retirement strategies, aiming at the ‘sweet spot’ which yields 94% of the full Age Pension, and supplemented by limiting savings caught under the Age Pension means test to $400,000. Any remaining extra savings will likely be placed beyond the assets test, for example into the principal residence and its renovation.

These perverse incentives stemming from the January 2017 changes are in marked contrast to the Simplified Superannuation Age Pension rules that applied until the end of 2016.

The key point shown in Chart 2 about those earlier rules is that for every $50,000 step up in super savings, the withdrawal rate of the part Age Pension was deliberately calibrated to ensure the saver received some increase in combined income from super savings and the remaining part Age Pension. There was no disincentive to save more, nor any incentive to dissipate existing savings in order to draw a larger Age Pension. The effective marginal tax rate on the income from additional superannuation saving between $400,000 and $1,150,000 was almost 80% — obviously very high — but an inevitable compromise in moving from full to no Age Pension without continuing fiscally costly access to the part Age Pension at excessively high income levels.

Fixing the mistakes from the 2017 Age Pension and superannuation changes

When a future government is forced to correct the mistaken 2017 changes in retirement income policy, it will first have to rebuild public confidence in rule-making for the Age Pension and superannuation system. A future government will have to offer a clear strategic vision for sustainable change, and demonstrate the long-term consequences of proposed change for both better retirement outcomes, and more sustainable Federal Budget outcomes. Such an approach will require published, contestable long-term modelling. It will have to consult meaningfully and assure savers and retirees that any future, significantly adverse changes that may be necessary, will include appropriate grandfathering provisions.

All these approaches have been used successfully in the past, but were abandoned for the changes taking effect in 2017.

Jack Hammond, founder of Save Our Super

Terrence O’Brien, former Treasury official

This article is based on a longer paper produced by the authors for Save Our Super. Click here to access the longer paper on the Save Our Super website. For more information on the author’s views about appropriate grandfathering, see SuperGuide article https://www.superguide.com.au/the-soapbox/super-changes-grandfathering-rules For more information on the specific super and Age Pension changes, see list of articles at end of this article.

About the authors

Jack Hammond: Save Our Super’s founder is Jack Hammond QC, a Victorian barrister for more than three decades. Prior to becoming a barrister, he was an Adviser to Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, and an Associate to Justice Brennan, then of the Federal Court of Australia. Before that he served as a Councillor on the Malvern City Council (now Stonnington City Council) in Melbourne. During his time at the Victorian Bar, Jack became the inaugural President of the Melbourne community town planning group, Save Our Suburbs.

Terrence O’Brien: Terrence O’Brien is a retired senior Commonwealth public servant. He is an honours graduate in economics from the University of Queensland, and has a master of economics from the Australian National University. He worked from the early 1970s in many areas of the Treasury, including taxation policy, fiscal policy and international economic issues. His senior positions have included several years in the Office of National Assessments, as senior resident economic representative of Australia at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, as Alternate Executive Director on the Boards of the World Bank Group, and at the Productivity Commission.

For more information

For more information about Save Our Super, see the advocacy group’s website Save Our Super

For more information about the July 2017 super changes, and the January 2017 Age Pension changes, see the following SuperGuide articles:

- https://www.superguide.com.au/smsfs/300000-retired-australians-to-lose-some-or-all-age-pension-entitlements

- https://www.superguide.com.au/smsfs/less-age-pension-fewer-australians

- Super changes (July 2017): Planning ahead for the 2017/2018 year https://www.superguide.com.au/retirement-planning/july-2017-super-changes

- Burden for retirees: Monitoring $1.6 million transfer balance cap https://www.superguide.com.au/retirement-planning/liberals-1-6-million-cap-pension-start-balances

- New $100,000 cap: Cut to non-concessional contributions cap https://www.superguide.com.au/boost-your-superannuation/immediate-cut-non-concessional-contributions-caps

- Concessional contributions caps to be slashed from July 2017 https://www.superguide.com.au/boost-your-superannuation/over-50s-contributions-cap-cut

Related sections

How super works Retirement planning SMSFs (Self-managed super funds) THE SOAPBOX super and tax

Related topics

$1.6 million transfer balance pension cap Age Pension Concessional contributions cap Federal Budget and superannuation Guest articles Income tax Making superannuation contributions Non-concessional contributions cap Superannuation News Taking a super pensiontax-free super superannuation strategies.

First published by SuperGuide on 26 June 2017.

1 ping

[…] The paper by Hammond and O’Brien, which is now on the Save Our Super website, is titled: “A retirement income and savings trap caused by the Coalition’s 2017 superannuation and aged pens…” […]