The Australian

June 2, 2018

Adam Creighton

Machiavelli wrote “nothing is more difficult than to initiate a new order of things, for the reformer has enemies in all those who profit from the old order and only lukewarm defenders in those who would benefit from the new”.

Forget lukewarm, try clueless. Whatever the impediments to 16th-century reform in Florence, they were nothing compared with what Financial Services Minister Kelly O’Dwyer faces if she tries to improve the efficiency and competitiveness of superannuation. Abysmal standards of financial literacy are endemic. Almost a third of Australians would rather be given $200 in cash than receive $2000 in superannuation, according to a 2014 Westpac survey. O’Dwyer will have the two most powerful vested interests in the country — finance and unions — arrayed against her.

Compulsory super, in place for more than a generation, has created the world’s longest gravy train, delivering more than $30 billion a year in fees to a vast army of fund managers, administrators, financial advisers, custodians, bankers, directors, unions, employer associations, lawyers, accountants and pen pushers. The flow of cash easily will exceed the national defence budget within a few years.

The Productivity Commission’s landmark report into super, released this week, laid bare the extent of the inefficiencies: one in three super accounts is unintentional, draining almost $3bn a year in fees from savings; poor-performing funds are setting up millions of workers on ordinary earnings to retire with $600,000 less in savings than they should receive.

The inefficiencies ultimately all stem from a level of competition “at best superficial”, the commission said. Indeed, six years on from the previous Labor government’s MySuper reforms, average fees fell a risible 0.03 percentage points to 1 per cent — about triple what large pension funds charge overseas — between 2016 and last year, according to Rice Warner. That means a typical family with a combined $300,000 is paying, probably unwittingly, about $3000 a year in fees, more than for electricity and gas combined.

Fees are evidently a sore point in the industry: fewer than 10 per cent of the 208 large super funds surveyed by the Productivity Commission bothered to provide any detailed information to it on investment management costs.

The heart of the commission’s solution was to wrench super out of the industrial relations system, creating a list of 10 funds to be chosen by an expert committee. For all the drama, this wasn’t particularly ambitious: only new workers, mainly disengaged young people, whose compulsory contributions amount to about $1bn a year would face the new list. Funds receive about $85bn a year in employer contributions.

The biggest vested interests, for-profit or retail funds run mainly by the banks and AMP, and the not-for profit or industry funds with links to unions and employers groups, were nevertheless outraged — the former because their woeful performance was highlighted once again, and the latter because any change could upset their ingrained advantages.

Industry funds trounced retail funds across the 12 years to 2016, delivering annual net returns of 6.8 per cent a year compared with 4.9 per cent by retail funds, and they will continue to.

Industry funds, born of the industrial relations system and deeply embedded in it, receive a huge advantage. They make up about 70 per cent of the default superannuation funds that appear in industrial awards and enterprise agreements, compared with 17 per cent for retail funds. These are the funds to which employers pay 9.5 per cent of workers’ wages if they don’t choose their own fund. Up to two-thirds of workers default into these funds when they start a new job, providing a reliable and growing river of contributions to default funds.

Ian Silk, chief executive of Australian Super, the biggest industry fund, conceded as much in an interview with former Labor MP Mary Eason published in her 2017 book, Keating’s & Kelty’s Super Legacy. “This has been the single most important investment-performance differentiator between the industry and commercial funds,” he told her. “The (industry fund) trustees could do, frankly, whatever they liked with the money knowing they weren’t going to be put under pressure by members saying ‘I want my money out’ ”. A captive market lowers advertising costs, too.

“The retail funds have not been able to do so to the same extent because most of their members are either themselves more engaged and more likely to move their money around … consequently, the liquidity requirements for retail funds are much higher.”

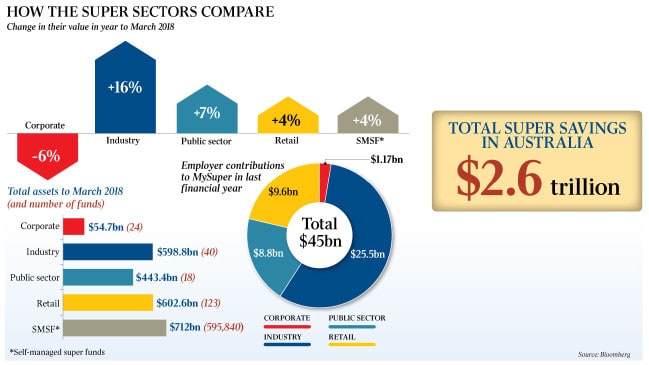

Indeed, for the past four years industry funds have enjoyed about 55 per cent of the compulsory contributions flowing into MySuper funds, more than double the share heading to retail funds. Across the year to March, industry fund assets grew four times as fast, up 16 per cent to $599bn, as retail funds. It’s not all easy money, though. Industry funds’ model and frugality also have helped keep costs low. For a start, no shareholders means no dividend cheques for shareholders.

“The pay in industry funds pales in comparison with what top bankers and fundies are earning,” says a Sydney partner of a multinational law firm who has worked in superannuation for decades. “The philosophy is totally different; they hate bankers driving Maseratis through Vaucluse.”

By way of example, AustralianSuper, with $123bn in assets across 2.15 million accounts, paid its chief executive, Ian Silk, under $900,000 last year, while its chairwoman, Heather Ridout, earned $192,000. Meanwhile, former AMP chief executive Craig Meller took home more than $8 million in pay and bonuses while his chairwoman, the now departed Catherine Brenner, earned $660,000. National Australia Bank’s wealth boss earned about $4m, about half what its chief executive earned.

“We’ve generated scale benefits to members as we’ve grown larger, through lower investment costs via better buying power with external fund managers and some internal investment management,” says Damian Graham, chief investment officer at First State Super, one of the biggest industry funds with around $90bn under management.

Industry funds also have kept costs down by sharing and owning support services run by intellectual fellow travellers. Industry Super Holdings, chaired by Garry Weaven, perhaps the most powerful man in super, is at the heart of a complex web of companies including Industry Funds Management, Frontier Consulting, Industry Funds Services, IFS Insurance Solutions and online newspaper the New Daily. Owned by the major industry funds, it has never paid a dividend. ISH now has more funds under management ($90bn) than Westpac.

Directors typically have strong links to the union movement. The wife of federal Labor leader Bill Shorten is a board director of some related companies.

As well as lowering costs through ISH, industry funds’ increased size and scale enable them to bring services in-house. First State Super’s investment team has grown from about 12 a few years ago to about 70, for instance.

The Productivity Commission’s report focused on efficiency, or lack thereof. Compulsory super’s structural flaws, however, are causing problems far beyond just a financial feast for the industry that puts pressure on the Age Pension. Union-sponsored directors on industry funds, which typically make up half the total, tend to give their fees to their union, while directors of for-profit funds keep theirs. In the four years to last year, the former gave more than $18m to their sponsoring unions, according to the Institute of Public Affairs. It’s telling the industry funds successfully blocked the government’s attempt to legislate quite modest tweaks to superannuation — requiring a third of directors on super boards to be “independent” and more granular disclosure of fund costs to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority.

Even Bill Kelty, grandee of the union movement and a father of superannuation, this week declared an “arguable case” for a government-run default fund, putting him on the same page as former Liberal treasurer Peter Costello, who has suggested the Future Fund should take default contributions.

The Productivity Commission dismissed the idea this week, but chronic apathy among members is unlikely to provide enough discipline to lower fees dramatically, however short the “best in show” fund list becomes.

New Zealand, Chile and Sweden have public tenders for the right to manage default pension funds. “This has reduced average annual super fees to between 0.30 per cent and 0.55 per cent in those countries. In Australia even default funds still charge double to triple this because of their risky active management strategies,” says Chris Brycki, chief executive of Stockspot. The giant US-based Thrift Savings Plan managed American retirement assets of about for less than 0.03 per cent a year in 2014, or 29c for every $1000 invested.

Fees are the biggest predictor of returns, given the impossibility of fund managers consistently achieving returns above the average after deducting fees. Industry funds have done a better job than retail funds of growing members’ funds — I’m in one myself. Yet a government fund could achieve the scale benefits of industry funds without the politicisation.

Meaningful reform has been glacial. O’Dwyer has a fight on her hands if she wants to take up the thrust the Productivity Commission’s recommendations, let alone back a government-administered no-frills option.