The Australian

June 2, 2018

Paul Kelly

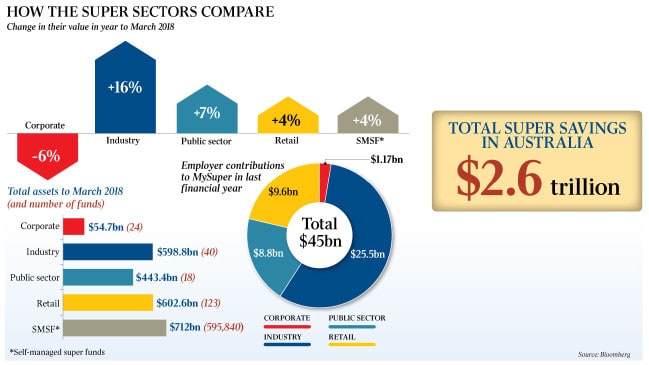

Fundamental reform of Australia’s unique $2.6 trillion superannuation industry is essential following the devastating Productivity Commission analysis this week — but the stage is now set for a titanic struggle over the design and dynamics of reform.

Superannuation in Australia is not just a retirement policy that shapes the living standards of older people. It is a compulsory system still tied to industrial awards and agreements that delivers a guaranteed flow of savings into funds, creating a huge financial edifice projected to be worth $9.5 trillion in less than 20 years, with the trade union movement a critical stakeholder via the successful industry funds.

Super is driven by two sometimes conflicting forces: the public or member interest and the vested interests of the big players. How this shake-out occurs will be decisive in future financial and political power in this country and living standards in retirement. The politics of super are complex, brutal and often in the shadows.

Consider the deliberations of senior cabinet ministers over the recent 2018-19 budget when Revenue and Financial Services Minister Kelly O’Dwyer brought forward a proposal — previously advocated by Peter Costello — for a universal based not-for-profit government agency to manage and invest default super.

This would have been a radical game-changer. It would have constituted the biggest reform to the super system since its inception by the Labor Party nearly three decades ago. O’Dwyer is close to Costello. She worked for him as an adviser when Costello was treasurer. She took up the idea that Costello, chairman of the nation’s sovereign wealth fund, the Future Fund, had put into the public marketplace in late 2017, speaking in a private capacity.

Members who decline to choose a fund — an extraordinary two-thirds of people — are placed into a default (MySuper) product, a result often dictated by awards or agreements. Total assets from default in the system are just under $600 billion and heading towards one trillion, testifying to the pivotal power of this policy for the funds. A cabinet minister called the system “one of the great sweetheart deals”.

Costello, champion of free markets, favoured a government agency fund to handle default, believing this was a superior model and replicated overseas experience in countries such as Canada.

But O’Dwyer’s proposal was rejected by Scott Morrison and Finance Minister Mathias Cormann, who were concerned about the downside of such a government-run agency operating as a superannuation national safety system. The Productivity Commission considered and rejected the Costello model in its report.

The report documents the failure of the super system for about a third of its members, the centrality of the default model as a problem and recommends reforms that, in their own right, amount to the biggest remake of the system.

While opposition Treasury spokesman Chris Bowen has kept open Labor’s options on the Productivity Commission report, the ACTU, the industry funds and board trustees are determined to fight for a core principle — keeping the super system tied to the industrial relations system. This is the heart of the issue.

The pivotal strategic aim of all key Coalition figures is to break this link — and the Productivity Commission report said it must be terminated in the interest of members since the labour market had changed so much over the past three decades.

O’Dwyer has embraced the report, given her defeat in the budget deliberations on the Costello model. She says: “This report shows the super system has not been working as effectively as it should for millions of Australians. The default arrangements are broken for those people who don’t choose where to put their money.”

The pre-budget debate among senior cabinet ministers reveals the extent of concern within government and by O’Dwyer, as relevant minister, at the underperformance of a third of the system, the financial leverage for the trade union movement via industry funds and the need for radical change.

The battle lines are still being drawn over the structure of the reforms. And there may be some surprises. Costello’s public stance for a government super agency and O’Dwyer’s effort to make this Turnbull government policy was one option. Another, likely to be embraced by the government, is the Productivity Commission-preferred model for an expert independent panel to identify 10 “best in show” funds from which default members can nominate thereby exercising choice.

Of course, yet another will be where Labor lands — it will probably seek to fix the problems of the underperforming funds yet retain the link between the super and industrial relations system.

O’Dwyer tells Inquirer: “It’s clear that superannuation should not be a plaything of the industrial relations system. The Productivity Commission has been very clear on that point. I like what the commission has come up with.”

This week’s events surely invite a reinterpretation of history. Quick quiz: what was the biggest mistake made by the Howard government in its final 2004-07 term? Excess spending? No. Excessive tax cuts? No. Surely its biggest mistake was running with Work Choices when it should have used its Senate majority to redesign the super system with a focus on member benefits and separating the funds from awards and the IR system. It had the legislative power but not the insight to grasp the situation of today.

Senior ministers have confirmed to Inquirer that the Turnbull government remains committed to the legislated timetable to increase the super guarantee rate in steps from its present 9.5 per cent of wages to 12 per cent by July 2025. The reality, however, is that it would be unconscionable for this rate to be lifted, allowing more savings to be compulsorily poured into the system, without prior comprehensive reform of the model that is ripping off so many member accounts.

The ACTU, the unions and the industry funds are unforgiving. The industry funds feel constantly vindicated, unsurprisingly, by their superior performance compared with the retail funds, owned to a large extent by banks. Costello says that with default funds eventually reaching a trillion dollars in a system that was compulsory, it is time for the government to “show an interest” as the scramble continues between funds over who gets the money.

Costello tells Inquirer: “You can have a slug-out between the industry funds and the retail sector. It’s been going on for decades. But perhaps a new and original idea should be injected into the decision-making.”

Senior ministers such as Morrison and Cormann feel otherwise. But former ACTU chief Bill Kelty, one of the original architects of the system, says there is an “arguable case” for the Future Fund to operate a default superannuation fund, saying he doesn’t think “every idea” Costello has is “bad”.

But the Productivity Commission’s rejection of the Costello model rests on firm foundations. It warns the “biggest risk” with a government-owned monopoly default fund would be political pressure to “top up” for poor performance, at the further risk of exposing taxpayers. Even before this possibility, having government responsible for fund performance creates potential political problems. The report also warns that “such a fund would fail to harness the benefits of competition for better member outcomes”.

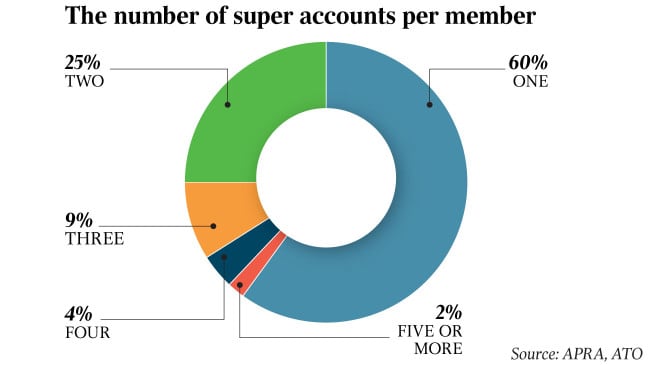

The commission says more than 80 per cent of men and women in their prime working years, 25 to 54, hold a super account. Fund investment performance varies wildly. Incredibly, four in 10 members have multiple accounts, usually unintended and at high cost in duplicate fees. There are 228 funds, mainly in four areas — industry, retail, corporate and public sector — and just under 600,000 self-managed super funds.

The system arose as a de facto extension of wages policy during the visionary Keating-Kelty 1980s Accord politics. Funds were tied to employers and unions via industrial awards and agreements. The commission’s analysis of 14.6 million accounts with MySuper products found those underperforming represented 31 per cent of member accounts compared with 67 per cent of accounts performing above the benchmark, many being large not-for-profit funds.

While a majority of members are in products performing “reasonably well”, this cannot be deemed to be satisfactory in a system based on compulsion.

Looking at the default segment in the decade to 2017, the top 10 MySuper products generated a median return of 5.7 per cent a year — but 1.7 million member accounts involving $62bn in assets were underperforming. The 26 underperforming funds were made up as follows: 12 retail, 10 industry, three corporate and one public sector. The dirty secret of the industry funds is that they have a long tail of underperforming funds.

The price of being locked into a bad fund is high: a typical full-time worker in a median underperforming MySuper product would retire $375,000 worse off than if they were in a median top-10 product.

A theme of the report is that the system seems more geared to the interests of the funds than the members.

The Productivity Commission assesses the system as a whole — its concern is not industry versus retail — and it finds the system wanting. Its analysis is based on member interest and returns. While ideology cannot be removed from this debate, the report, in effect, is telling the Turnbull government its focus must be system-wide reform based on public interest — not just bashing up the industry funds. Such an approach will be essential to obtaining sufficient support for major reforms.

The problems are systemic. The Productivity Commission makes clear the defects are fund governance, lack of competition, inadequate regulation, insufficient independent directors and unintended multiple accounts. It argues the dividends from reform would be immense — even for a 55-year-old today the improvement from a good fund could be an extra $60,000 by retirement and for a workforce entrant the gain could be $400,000 at retirement.

The report finds the defects in the system are highly regressive. The people being hurt are the young, low-income earners and people who frequently change jobs. For the unions and Labor, who campaign endlessly on inequality, this reveals a malaise inside their own castle. It presents them with a test of values and integrity — do they fix the infection or just defend their institutional vested interests?

ACTU assistant secretary Scott Connolly says superannuation is an “industrial right” — making clear it must remain anchored in the industrial system. “The suggestion that members’ interests are best served by breaking the link between industry awards, workers representatives and employer bodies which has driven the strength of industry super is badly misguided,” Connolly says.

He declared the for-profit funds “should be banned” and dismissed the Productivity Commission recommendation for an expert panel — separate from the Fair Work Commission — to draft the “best in show” shortlist to replace the existing default model.

The ACTU position was categorically rejected by the Productivity Commission. The report insists the Fair Work Commission should have no role in any new default model — its statutory responsibility is workplace relations, not dealing with super funds. The report says the time has long gone when super funds should be specified in awards and workplace agreements.

Industry Super Australia, representing the industry funds, demanded total control of the default process. Its chief executive, David Whiteley, said: “The job of government now is to ensure that workers who do not choose their own super fund have their interests protected and are defaulted into an industry super fund. This is currently the role of the Fair Work Commission and is in the best interests of members. Superannuation is deferred wages and a condition of employment.”

Get the message? Reform is OK but don’t use the public interest to dismantle the guaranteed flow of savings by law into the industry funds.

In the end this will become a huge contest over financial and political power, with the public interest being used as the rationale.

If you want to grasp the superior strategic skills of the broader Labor movement in Australia there is no better example than the creation, growth and present operation of the super system. The conservative side of politics is now deeply alarmed at this power and how it might be used. The real issue is: can the system be reformed or has it gone past the tipping point?

The Turnbull government has two super reform packages now being advanced. The first is a series of measures before the Senate requiring trustee boards to have one-third independent directors; to strengthen the powers of APRA to intervene and impose corrective action where a fund fails to uphold member interests; and to permit freedom of fund choice for about one million workers now denied it.

The second package was announced in the budget. It bans exit fees on all accounts, protects low-balance accounts by transferring them to the ATO after 13 months of inactivity and will empower the tax office to proactively reunite lost super with active accounts.

Reforming the system will be a difficult task for the Turnbull government — yet the public interest case for reform is unquestionably strong. The government, however, must beware merely waging an ideological war. It will be tempting. To an extent, it is justified. But it is not the road to success.

Thursday, June 28, 2018