Jim Bonham* saveoursuper.org.au

On 22 January 2021, the Australian Financial Review featured a front-page article by John Kehoe and Michael Roddan headed “‘Ever more’ super gets hoarded: Hume”. 1

In the same issue, Jane Hume (Minister for Superannuation, Financial Services, and the Digital Economy) provided an op-ed “Safety nets let frugal retirees spend savings without a super rise”. 2

On 23 January 2021, Kehoe followed up with an article entitled “Push for seniors to dig deep into super nest egg” in which he wrote:

“Superannuation Minister Jane Hume kicked off a national debate about retirement incomes this week …

“She said people needed to be more confident to spend – not hoard – retirement savings to improve living standards throughout their lives …

“The government’s retirement income review led by former Treasury official Mike Callaghan identified that many retirees died with most of their wealth intact and did not run down their super or tap equity in their home, so they might be saving too much”. 3

It is clearly an important national question. Wealth includes the home and other assets as well as super, but because the regulatory, financial, market, liquidity, and social issues in relation to housing differ so much from those applying to super, this article focusses only on super.

Is it true that retirees hoard their super? The answer is in three parts:

- Yes, in nominal terms, in some cases,

- No, in real terms (indexed to wages),

- No, when considered as an average across all retirees.

The Minister’s view, as presented in the op-ed2 and reported in the articles mentioned1,3, is rather different, but it is strongly supported by the Retirement Income Review – Final Report (20 November 2020), chaired by Michael Callaghan4 (“RIR Report”).

A couple of quotes give the flavour of the RIR Report’s attitude (page numbers refer to the pdf version4):

page 23, “Most people die with the bulk of the wealth they had at retirement intact.”

page 56, “The evidence suggests that retirees tend to hold on to their assets … Alternatively they need not have saved as much …”

It seems the way is being paved towards downgrading the level of compulsion applying to super contributions for pre-retirees and tightening the requirements for withdrawal in retirement. Such changes may be damaging to retirees if they are not soundly based on facts and understanding.

The counter-arguments to the claim that super is being hoarded by retirees need to be fleshed out:

- Nominal hoarding

Superannuation kept in an allocated pension account, as is typical for retirees, is subject to minimum annual withdrawal limits. Those rates have been halved for 2019-21 because of Covid-19, but normally they are: 4% below age 65, 5% for ages 65-74, 6% for 75-79, 7% for 80-84, 9% for 85-89, 11% for 90-94 and 14% over 94.

Provided that investment returns can keep up with the minimum withdrawal rates from an allocated pension it is possible, with care, to leave the capital (in nominal dollars) untouched and take only the investment returns as income.

However, this becomes increasingly difficult beyond age 80 as the minimum withdrawal rates increase well beyond 7%, or at much younger ages if investment returns are low.

Hoarding of nominal superannuation capital throughout retirement is therefore possible, but only for those who die early or invest well.

- Real hoarding

Nominal dollars provide a poor base for comparison across long time periods. Real values, indexed to wages, relate much better to community living standards. If the super account maintains its nominal value for 15 years, it will have lost almost half its real value (assuming 4% p.a. long-term wages growth).

Successfully hoarding real capital between 65 and 74 years of age would require nominal investment returns, net of fees, consistently above 9%. This is possible during good times, but almost impossible in bad times, and it becomes far harder as the superannuant ages further.

There is a simple reason for that: the minimum drawdown rates are designed to prevent long-term hoarding, whilst enabling those who live a long life to continue to benefit from their savings.

- Average hoarding

It is easy to trot out simple examples to show that capital can or cannot be preserved in various scenarios. From a policy point of view, however, what matters is the true average behaviour of all retirees.

In support of the claim that retirees do not consume their capital, the RIR Report4 cites a paper by Polidano et al 5, and re-plots Fig 2 of that paper as Fig 5A-12 on page 434 (pdf version). That graph shows average superannuation account values at a point in time, as a function of age, thus neatly dodging the inflation issue.

At first sight, that graph seems to confirm the hoarding thesis – although some drop-off in account value can be seen for ages in the late 70s.

On page 434 (pdf version), the RIR Report4 states: “Superannuation assets have tended to grow in retirement (Chart 5A-12), instead of declining as would be expected if assets were funding retirement”.

Polidano et al 5 similarly state that they find “little evidence that people, on average, run-down superannuation balances after reaching the preservation age (Figure 2).”

Both comments support the hoarding hypothesis, but closer inspection reveals that the graph pertains only to the average of non-zero-balance accounts. In other words, those accounts which have been totally withdrawn have been excluded.

This is an example of “survival bias”. A similar situation can arise when back-testing share investment criteria against past data, if consideration is limited to companies that are still in business. Ignoring those that have failed can be an expensive mistake.

In the present case, the survival bias may or may not matter, depending on one’s purpose; but when the purpose is to establish that retirees hoard their super, it matters a great deal.

Fortunately, Table 1 of Polidano et al 5 provides valuable additional data: average account balances are listed there both for accounts with non-zero balances, and for all accounts – segregated further by gender. That allows the survival bias effect to be both quantified and eliminated. It is substantial: roughly 80% of males are shown as having exhausted their accounts by age 80.

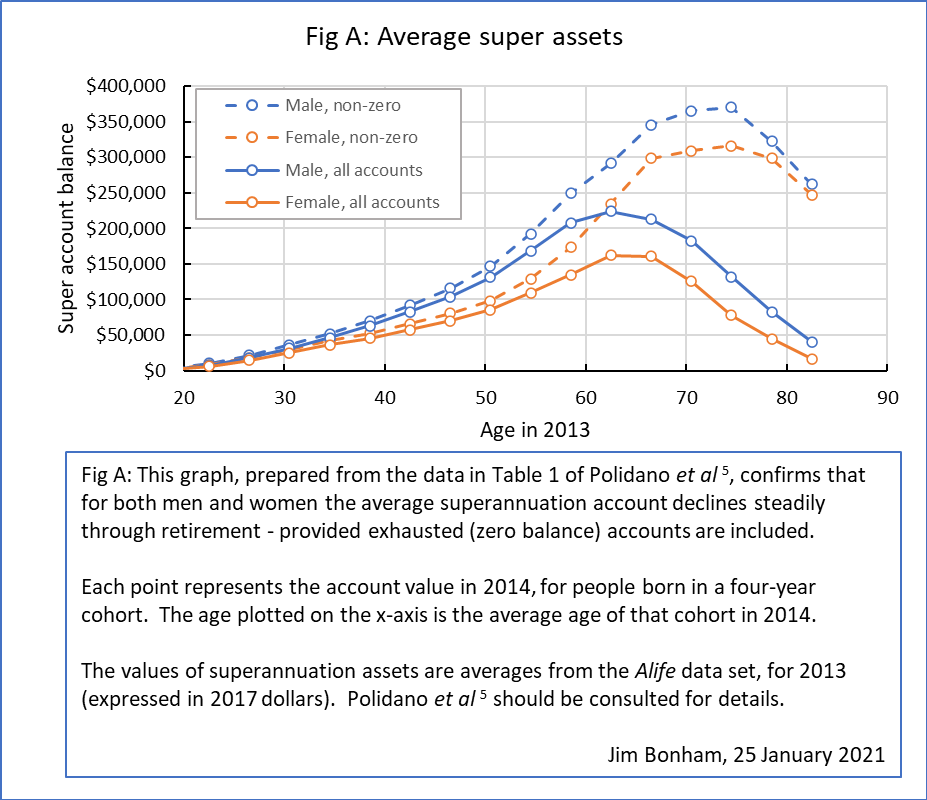

To make the impact of the account survival bias easier to see, Fig A below plots the Alife data from Table 1 in Polidano et al 5, for all accounts and for non-zero-balance accounts.

A discussion about how fast, if at all, people consume their superannuation in retirement must include all accounts to be meaningful.

As shown in the two solid all-accounts curves in Fig A – blue for males and orange for females – there is a strong and steady fall-off in the average all-accounts value throughout retirement, at least to the early 80s, by which time most or all of the average balance has gone.

Conclusion

The notion that retirees, averaged across the population, hoard their super is thus contradicted by the facts.

That is an important conclusion when considering superannuation policy.

[1]John Kehoe and Michael Roddan, “ ’Ever more’ super gets hoarded: Hume”, The Australian Financial Review, 22 January 2021, pages 1,2 https://saveoursuper.org.au/wp-content/uploads/ever_more_super_gets_hoarded_hume-afr-22Jan2021.pdf

[2] Jane Hume, “Safety nets let frugal retirees spend savings without a super rise”, The Australian Financial Review, 22 January 2021, page 35 https://saveoursuper.org.au/wp-content/uploads/safety_nets_let_frugal_retirees_spend_savings_without_a_super_rise-afr-22Jan2021.png

[3] John Kehoe, “Push for seniors to dig deep into super nest-egg”, The Australian Financial review, 23 January 2021, page 2 https://saveoursuper.org.au/wp-content/uploads/push_for_seniors_to_dig_deep_into_super_nest_egg-afr-23Jan2021.png

[4] https://treasury.gov.au/publication/p2020-100554

[5] Polidano, C. et al., 2020. The ATO Longitudinal Information Files (ALife): A New Resource for Retirement Policy Research, Working Paper 2/2020, Canberra: Tax and Transfer Policy Institute, available at https://taxpolicy.crawford.anu.edu.au/publication/ttpi-working-papers/16448/ato-longitudinal-information-files-alife-new-resource .

A final version of that paper, in which some errors are corrected, has been published in The Australian Economic Review, September 2020, vol 53, No 3, pp 429-449.

* Jim Bonham PhD, BSc, Dip Corp Mgt, FRACI is a retired scientist and manager with a professional background which was initially in academic physical chemistry, and subsequently in applied research and development in the paper industry. He has been running an SMSF since 2003 and has a keen interest in the retirement income system.

25 January 2021

****************************************

On 28 January 2021 an abridged version of this article was published by SuperGuide (https://www.superguide.com.au/how-super-works/do-retirees-hoard-their-superannuation).

Postscript

On 31 January 2021 Senator Jane Hume, Minister for Superannuation was reported as saying, amongst other things, that “[retirees are] passing away with most of their retirement savings intact” ; see “Hume urges retirees to use super capital, rather than just returns” by Emily Chantiri, Sunday Age, https://www.theage.com.au/money/super-and-retirement/hume-urges-retirees-to-use-super-capital-rather-than-just-returns-20210129-p56xv8.html