Jack Hammond, QC

Terrence O’Brien, B Econ (Hons), M Econ

12 May 2017

We support The Shepherd Review’s Statement of National Challenges, and wish to offer some comments on how best to constrain the unsustainable growth of Commonwealth Government expenditure on the age pension.

The Review states, correctly as far as it goes, that:

The 2015 Intergenerational Report showed even after 50 years of compulsory superannuation there is no significant reduction in the number of Australians drawing on a publicly funded pension. In 2050, some 80 per cent of Australians beyond retirement age will be entitled to the Aged Pension in full or in part. It represents almost no change to today’s call on the public pension system which costs Australia $44 billion in 2015-16. (p 11)

However, that account (which, to be fair, is a very common one) does not acknowledge the considerable move from reliance on the whole pension to the part pension, facilitated by the 2007 reforms to the pension and superannuation systems introduced in the Costello Simplified Superannuation package. That important progress is discussed at pages 3 and 4 below, and could be built on in reforms for the future, if recent retrograde changes can be undone.

The challenge is to maintain the momentum of increasing super savings, so that over time those in a position to save more, move though part-pension/part-super retirement strategies to becoming completely self-reliant in retirement.

Instead, the retirement income architecture created by the 2017 changes to pensions and superannuation is inherently unstable and unsustainable. Many savers are now locked in by perverse policy incentives to continued reliance on a part pension, and additional super saving is penalised. Trust in superannuation has been seriously damaged, together with a destruction of trust in how the retirement income rules will be further changed in future.

Politically feasible retirement income policy reforms

The retirement income system should facilitate Australians’ legitimate aspirations to build higher living standards for themselves in retirement.

- General community living standards are rising over time.

- Australians are living longer with more years of active, healthy retirement.

- People are financially more capable of saving for their own retirement than ever before.

- The population structure is ageing, and consequently the largest ‘unfunded defined benefit scheme’ of all, the age pension, will require higher public expenditure from taxes bearing on proportionately fewer working age Australians.

- The income tax system – a progressive tax on nominal income – and the availability of the age pension continue to constitute large disincentives to long-term saving.

- Reducing the tax and pension disincentives to saving will both increase savings and efficiently allocate them through capital markets to the highest value investments.

- In contrast, reliance on a government age pension, even a policy which locks in an enduring reliance on a part-pension, necessitates ever-higher tax revenues, with all the dead-weight costs of taxation.

Recent policy reversals destroy trust in private saving for retirement

In the case of the age pension, the restrictions announced by Treasurer Hockey in the 2015-16 Budget that took effect on 1 January 2017 reverse the more gradual pension taper introduced from September 2007 by Treasurer Costello as part of the 2006 – 2007 Simplified Superannuation package. That package was the system that pensioners now aged in their seventies and eighties based their savings and retirement decisions on.

The extensive consultative processes surrounding the Simplified Superannuation exercise commented on the severe pre-2007 assets test that then applied (and that has now been re-introduced):

The assets test is very punitive as retirees must achieve a return of at least 7.8 per cent on their additional savings to overcome the effect of a reduction in their pension amount. This high withdrawal rate creates a disincentive to save or build retirement savings. ….

It is proposed that the pension assets test taper rate be halved from 20 September 2007 so that recipients only lose $1.50 per fortnight (rather than $3) for every $1,000 of assets above the relevant threshold. This would mean that retirees would need to achieve a return of 3.9 per cent on their additional assets before they are better off in net income terms — that is, after taking account of the withdrawal of the age pension. …..

The reduction in the assets test taper rate would increase incentives for workforce participation and saving especially for those people nearing retirement who will still depend on the age pension to fund part of their retirement.[1]

So the gentler asset test taper introduced in 2007 was consciously conceived as a pro-saving measure, assisting the growth of retirement income levels by encouraging those who might have had to rely on just a full age pension to instead achieve higher living standards from a combination of a part age pension supplemented by savings in a simplified superannuation system. The gentler taper in the post-2007 pension asset test ensured that effective marginal tax rates on saving were not excessive, and offered savers perceptible gains in retirement living standards from their lifetime saving efforts.

The simplification exercise was carefully researched, meticulously documented and explained in an extensive discussion paper; open to lengthy and meaningful community consultation; subjected to extensive published modelling of long term effects on pensions, retirement income and government expenditures and tax expenditures; and realistically costed. Those are all virtues lacking from the 2017 pension and super changes.[2]

In 2007, the then Treasury Secretary, Dr Ken Henry, said about Simplified Superannuation that

…. as an exercise in policy leadership, the superannuation reform is as good as anything I’ve seen the department produce in the 20-odd years of my Treasury career.[3]

Unfortunately, the 2017 superannuation changes follow exactly the same path as the pension changes: i.e. they are the direct reversal of a previous incentive after peoples’ saving has been attracted and trapped within the super system. Treasurer Costello’s Simplified Superannuation concentrated super tax on the contribution and accumulation phase, but Treasurer Morrison reversed that by reintroducing both tax on the drawdown phase and massive complexity. The transfer balance cap paraphernalia comes with extremely complicated support structures of Personal Transfer Balance Caps, Transfer Balance Accounts, Total Superannuation Balance Rules, First Year Cap Spaces, Crystallised Reduction Amounts, Excess Transfer Balance Earnings and Excess Transfer Balance Taxes.[4]

Retirement income changes have slow effects, and need to be carefully modelled

The impacts of any pension and super changes have very long term effects, interactive with demographic and economic changes, and require detailed modelling to tease out the complex interdependencies over the long run. Since 1992, Treasury has maintained a specialized unit, now called the Retirement and Income Modelling Unit, to analyse tax, pension and super policy changes, and to assist distributional analysis and intergenerational modelling over the necessary multi-decade time frames. The modelling has used a large cohort model known as RIMGROUP.[5] In 2012, Treasury updated modelling incorporating the 2007 Simplified Superannuation pension and super changes and other significant retirement policy changes up to 2012. Its key trends are shown in the chart on page 4.

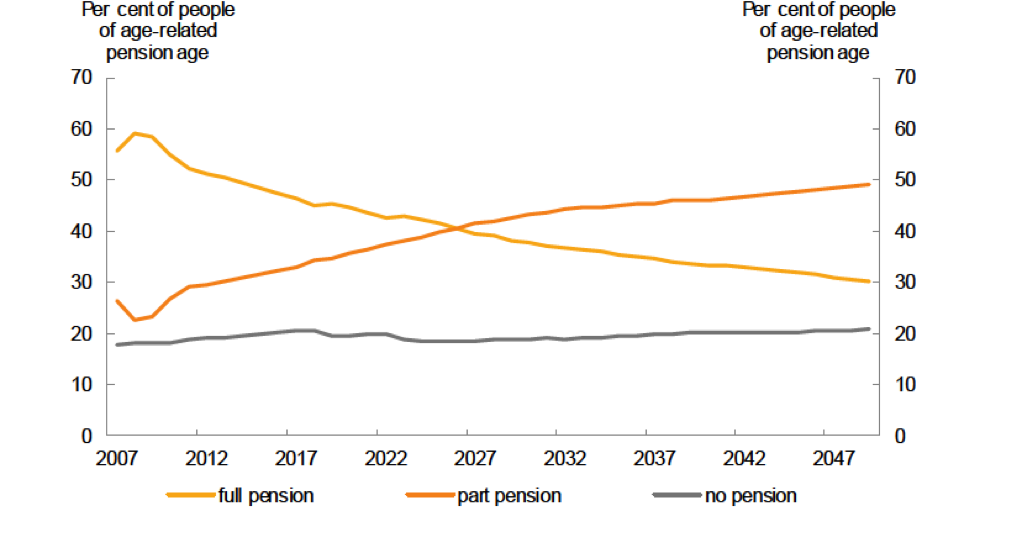

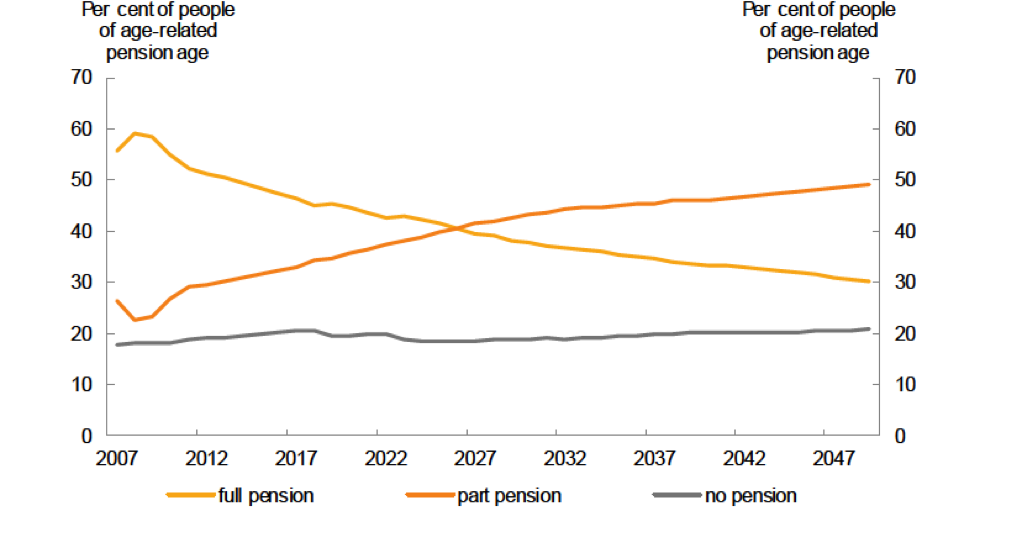

In summary, the modelling suggested the Simplified Superannuation pension and superannuation measures were performing exactly as intended to help reduce dependence on the full age pension and bolster saving to lift retirement living standards. On policies applying in 2012 (including the scheduled increases in the Superannuation Guarantee Levy), Treasury projected that those dependent on the full pension would fall from about 50% of the age-eligible cohort in 2012 to only 30% over the years to 2050, while part-pensioners would correspondingly rise from about 30% to 50%. However only about 2-4% of those eligible by age for the pension would move to fully self-funded retirement, which would remain stubbornly low at about 22%. This is partly because as life expectancies continue to rise into the future, retirees would ultimately exhaust their super savings and would revert to part or full pensions in late old age.[6]

Percentage of age-eligible retirees receiving full age or service pension, part pension, or self-funded (i.e. no pension)

Source: Treasury RIMGROUP modelling, cited in Jeremy Cooper et al, A Super Charter: Fewer Changes, Better Outcomes, July 2013, p 13.

It is of course possible to envisage even larger retirement living standard gains (or lower revenue costs) from better-tuned policies, as long as savers trust the rules for changing policies and maintain confidence in predictable access to their life savings in super or in access to the pension.

As for the long-term sustainability of the system created in 2007, the modelling paper concluded in 2012:

….. Australia is in a very strong position in relation to the sustainability of its retirement income arrangements compared with almost any other country in the world. However given the significant part of the government’s budget involved, the increasing costs as the population ages and the many factors influencing sustainability, this relative strength should not lead to complacency.[7]

Curiously for a Government presumably keen to demonstrate the virtues of its policy changes to the age pension and super in 2017, there has not been any more recent public release of RIMGROUP modelling to show the long-term effects of the 2017 measures.

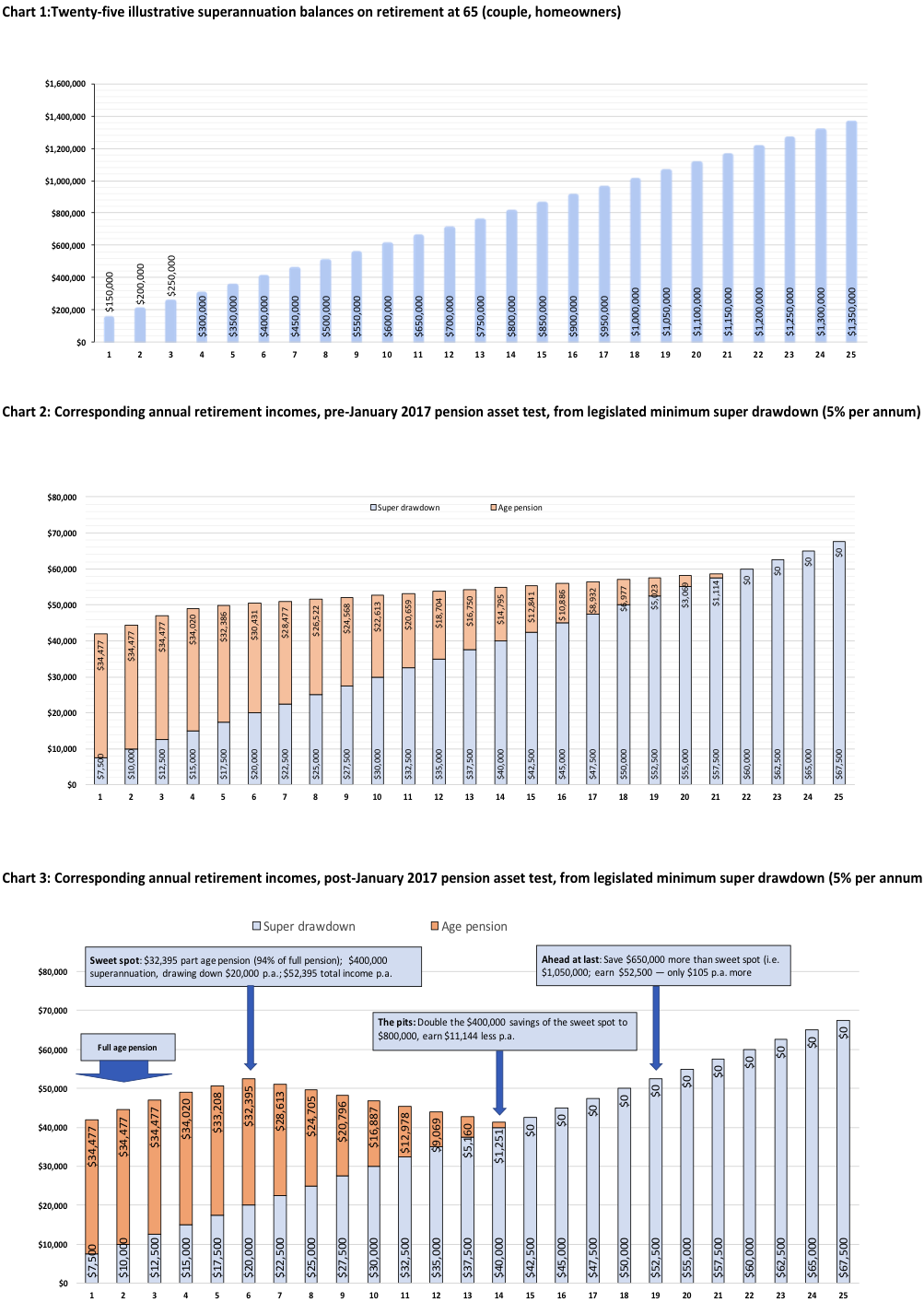

A wide super saving trap

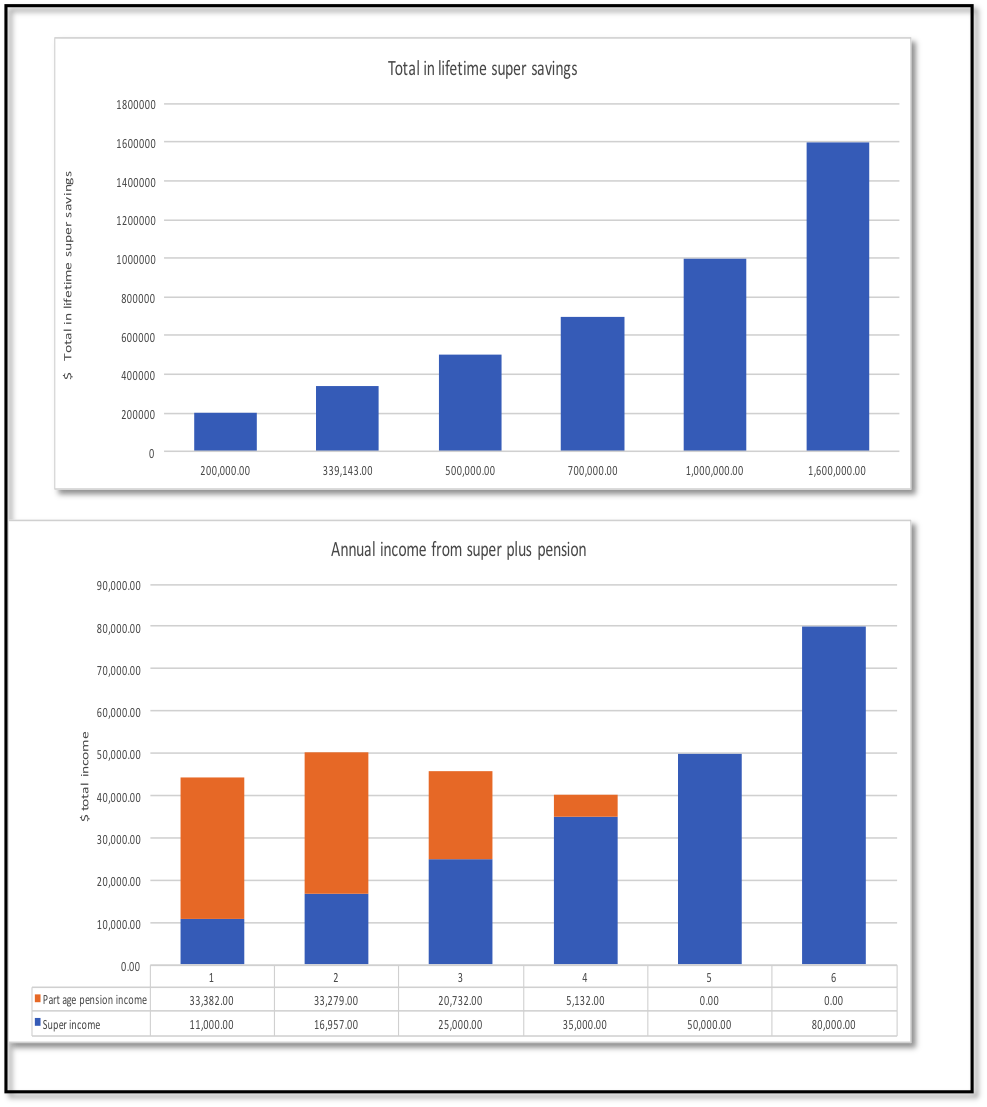

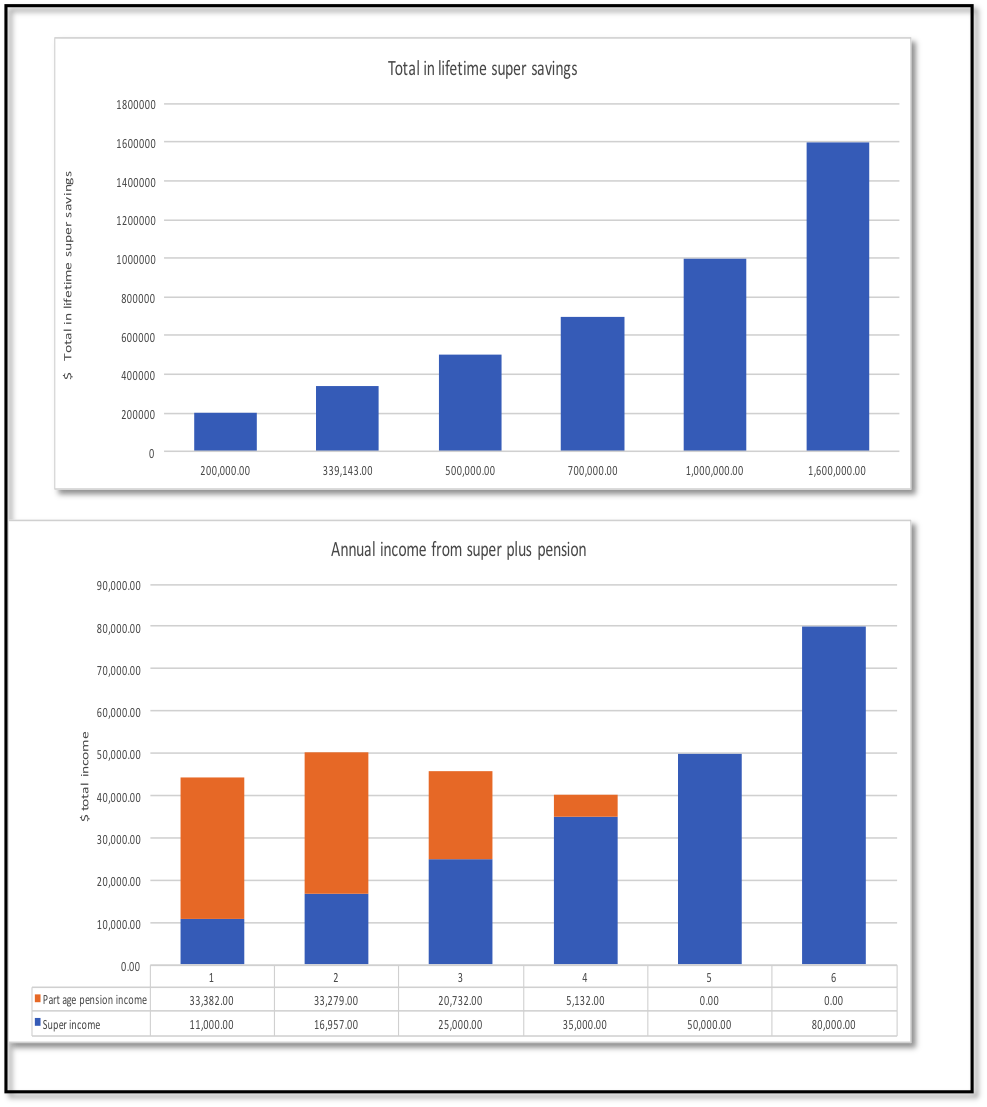

The higher pension taper is a large increase in effective marginal tax rates on part pensioners. While people in the workforce can often adjust to an increase in the marginal tax rate on their annual income by working more hours, seeking promotion, or training for a better paid job, those long retired have no such options. Higher effective marginal tax rates from a sharp asset test taper lock people in an extended income trap of dependency on a part pension and small savings, as enumerated in the charts on page 6. As the charts illustrate, over a wide range of lifetime super savings from $200,000 to $1,000,000, savers cannot lift their annual retirement income above about $50,000. Indeed, they go backward if they save more than about $340,000 but less than $1,000,000.

Flatlining retirement income: The $50,000 per annum trap

Sources: Derived from Tony Negline, Saving or slaving: find the sweet spot for super, The Australian, 4 October 2016, and Save more, get less: how the new super system discriminates, The Australian, 26 November 2016

Assumptions: 1. Married couple, both aged 65 or more; 2. Own home, debt free; 3. $50,000 personal use assets including car; no other assets; 4. Super saving pays eligible allocated pension at 5% pa, tax free. 5. Eligible super pension commenced after Dec 2014, so account balance deemed in Centrelink income test.

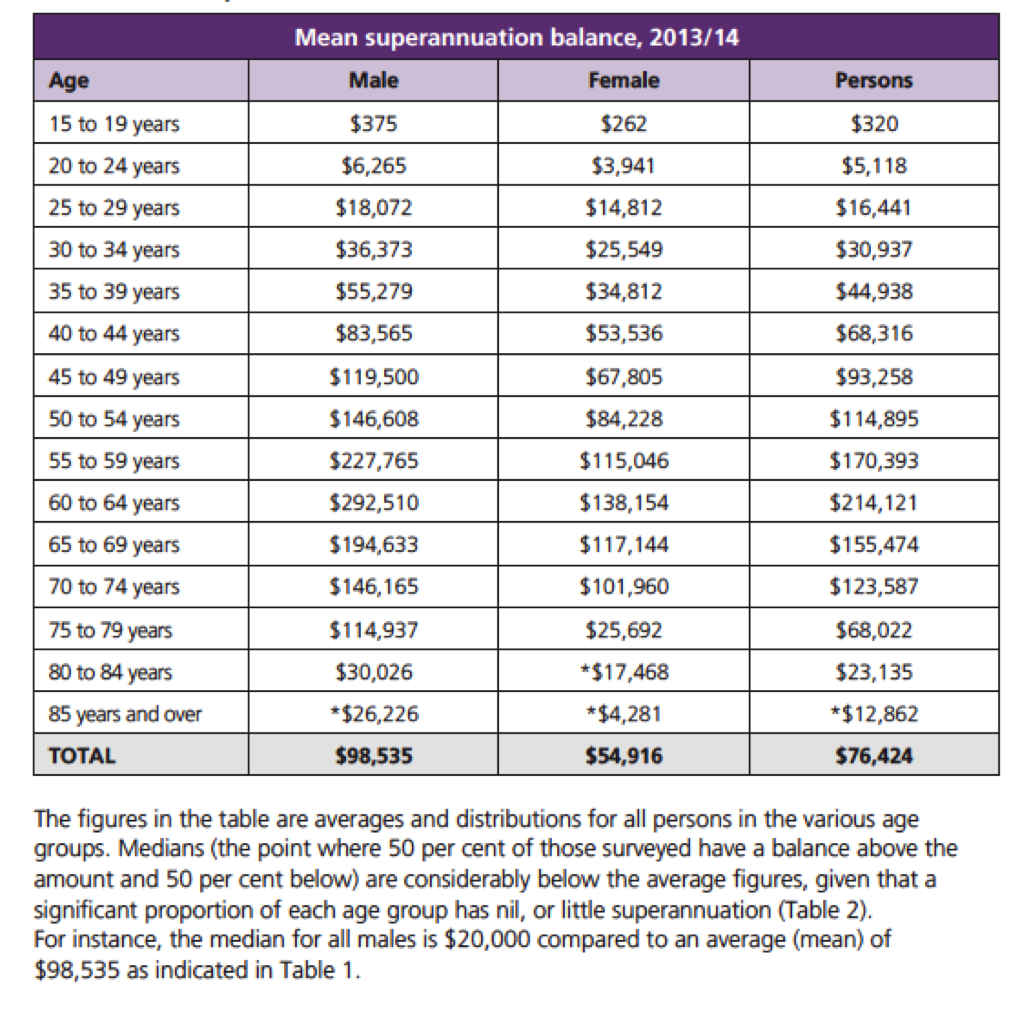

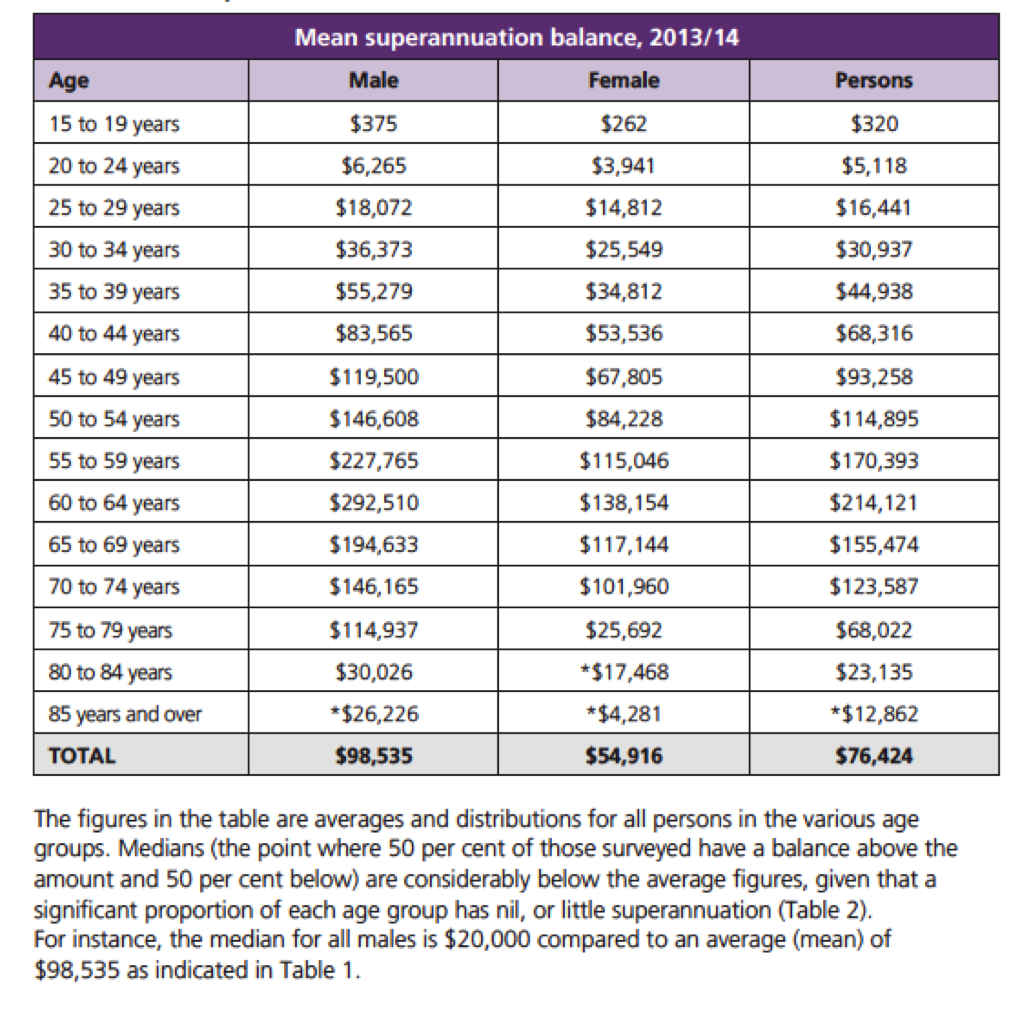

In practice, this asset test trap over the $200,000 to $700,000 range is a very relevant problem, as the range of mean super balances now reported for males nearing retirement age is around the bottom of the flatline zone, but plausibly within reach of the ‘sweet spot’ where retirement income is maximized, as illustrated in the following table.

Source: Ross Clare, Superannuation account balances by age and gender, December 2015.

Intergenerational fairness is not helped by the 2017 changes

It is incorrect to view these issues as improvements in intergenerational fairness, with generous treatment of current retirees coming at the expense of young workers. All are affected, as reports of modelling by Sean Corbett illustrate:

…..a young person who starts work on an annual income of $50,000 and contributes $15,000 a year of additional super contributions from age 52 can now expect to have a lower income in retirement than someone starting work on $40,000 and doing the same.

Corbett’s analysis shows a staggering rise in the rate at which the savings of middle-income younger workers will be clawed back: under the previous rules, a $300,000 increase in private savings would have generated about $200,000 in retirement income. Thanks to the change in the rules, almost half of that $200,000 increment will be offset by lower pension eligibility, implying an effective tax rate on retirement savings of close to 77 per cent.

Given those tax rates, accumulating a substantial superannuation balance will hardly seem worth the sacrifice. Comparing, for example, two superannuants, one with a balance on retirement of $1.2 million and the other with $245,000, Corbett estimates that the 500 per cent difference in their accumulated savings will lead to a difference of just 20 per cent in retirement incomes.[8]

New barriers to hurdling the super saving trap

The 2015 restrictions by Treasurer Hockey on the age pension, which would by themselves have been onerous on present pensioners, now have their costs compounded by the 2016 restrictions on superannuation savings by Treasurer Morrison. Those trying to supplement their pension-based living standards through super saving, or trying to save enough to self-fund their retirement, feel themselves caught in a pincer movement. The severe part-pension taper restricts the net return on modest super savings. The restrictions on concessional and non-concessional super contributions and the obstructions of the transfer balance cap make it more difficult to break out of the income trap that encourages persistent reliance on the part pension.

The lack of appropriate grandfathering surrounding the Hockey and Morrison measures is seen to be unjust. It is understood to be destructive of trust in super and pension rules, and very damaging to any future attempts to improve retirement income policy. The “rules about changing the rules” have been torn up.

Now that the practice of grandfathering has apparently been abandoned by the Coalition, Labor and the Greens, it is dawning on all Australians that anything could happen in any future retirement income policy change, with ‘effectively retrospective’ impact.[9] That is very damaging to policy reform for the future, and risks any intelligent discussion of options being shut down immediately by ‘scare campaigns’ which, on the last few years’ experience, may be well-founded.

The Review’s forthcoming options paper on balancing the budget could play a vital role in rebuilding trust, and in putting revenue gains from policy change on a credible, supportable, sustainable, albeit slower-track approach.

The Review could do this by advocating appropriate grandfathering provisions in relation to the 2017 super and pension measures. This would guarantee all who had made legitimate and lawful savings and retirement decisions on the rules that have prevailed over the last decade that their plans could last their lifetime, while new policy would take effect progressively for those who were given sufficient time to adapt to it. This is what Treasurers Keating and Costello did in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s for all significantly adverse changes to super and pension conditions.

To give a simple comparison of ‘pension and super reform, right and wrong’:

- The age pension qualifying age for those born after July 1952 will increase by six months to 65.5 in July 2017, as announced in the 2009-10 Budget. That Budget announced that the qualifying age will continue to rise gradually to 67 by 2023 for those born after 1 January 1957. Thus those nearing retirement were given between 8 and 14 years notice to maintain their employment, save for and plan their transition out of the workforce.

- In contrast, the Hockey pension changes significantly increases in the effective marginal tax rate on non-pension income in January 2017 (reversing the more generous Costello treatment introduced in 2007) were only announced in the 2015-16 Budget. So those already retired on the basis of the income and asset tests implemented through Parliament in 2007 had less than two years’ notice of a decrease in their living standards that they had no means to adjust to.

- And in further contrast, the Morrison super restrictions in the 2016 Budget upend late career savings plans, and the retirement living standards of those with savings or defined benefit pensions deemed to be above the transfer balance cap, with little more than one year’s notice.

This changing practice looks perverse: slight changes adversely affecting those with relatively plentiful adjustment options were carefully signalled long in advance and grandfathered. Major changes significantly reducing the living standards of those who saved and retired on the basis of the 2007 Costello rules and now in their 70s and older were implemented in 2017 with practically immediate effect.

The inclusion of grandfathering provisions would be fiscally responsible: emerging problems claimed to be structural products of pension and super rules would be fixed structurally, and with credibility because of wider community support in a gradual, fair, sustainable adjustment.

Most importantly of all, any emergent retirement income policy problems or costs could be addressed open-mindedly, intelligently and in a spirit of goodwill, free of the pushback the Government’s approach has caused, and which will be even worse the next time someone raises a proposal for pension or super change.

Why re-opening reform of retirement income policies is essential, and urgent

The retirement income architecture created by the 2017 changes to pensions and super is inherently unstable and unsustainable. Trust in the age pension and super saving have been seriously damaged, together with a destruction of trust in how the retirement income rules will be further changed in future.

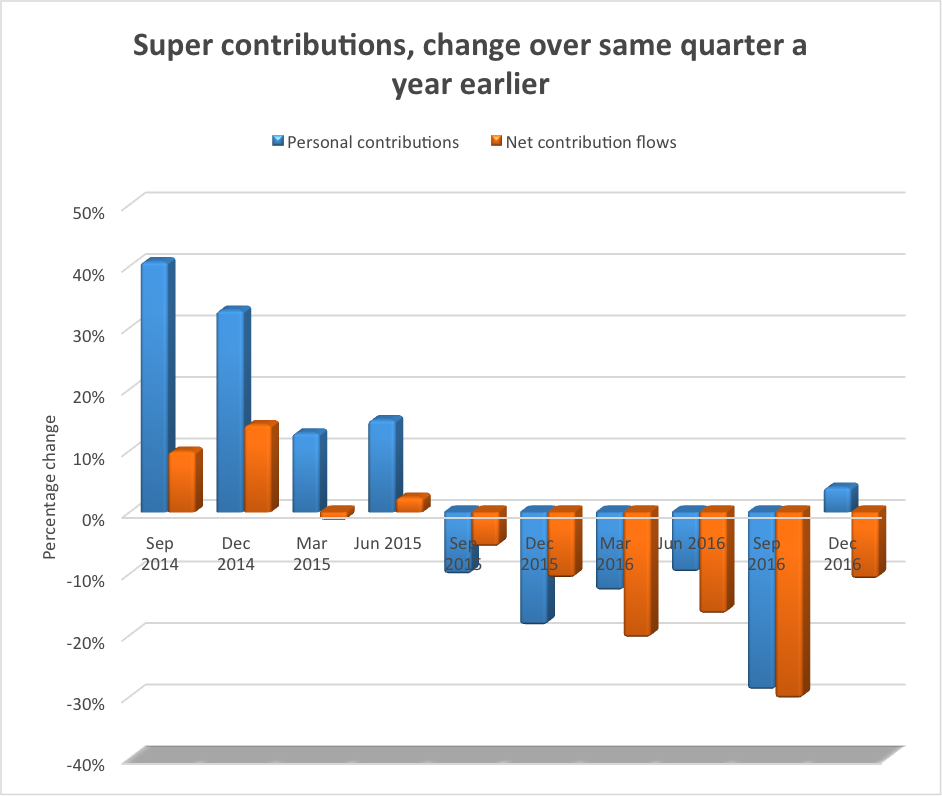

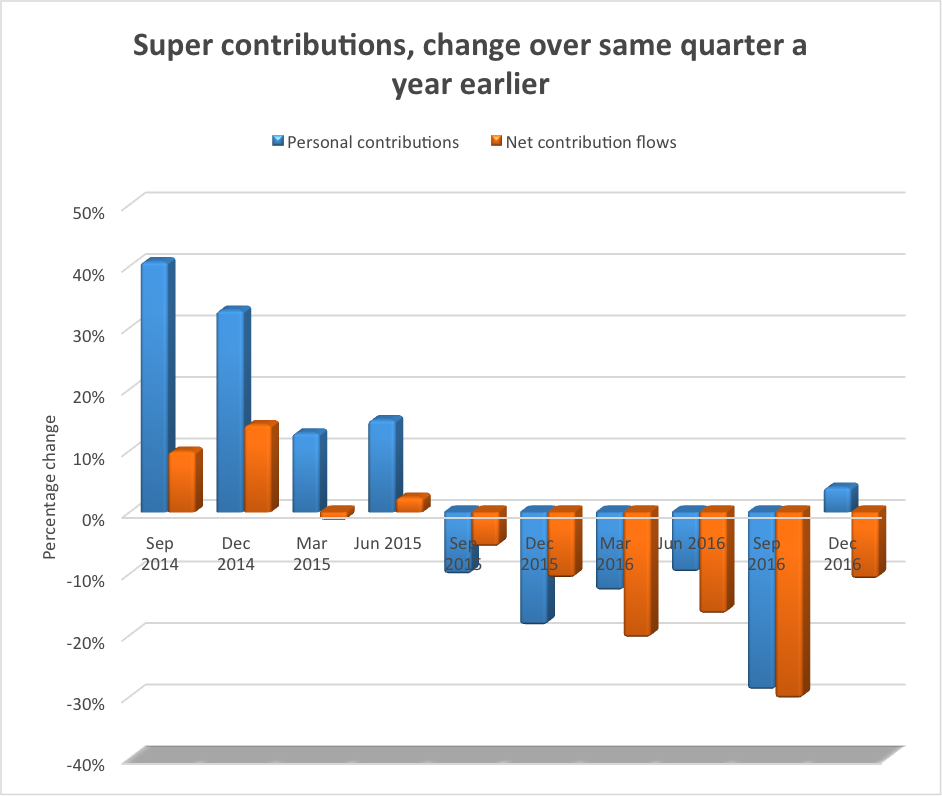

Consequently, the Government’s forecast revenue gains from the changes will prove greatly overstated. We consider the dominant savers’ responses to the 2017 measures will be:

- a departure of funds from super (in part triggered by complexity, higher compliance costs, fear of future changes, and by the $1.6m transfer balance cap);

- a drought in new ‘personal contributions’ into super (i.e. concessional and non-concessional contributions beyond the Superannuation Guarantee’s compulsion); and

- a displacement of saving effort outside the financial sector and into other tax-efficient savings vehicles such as the principal residence and its furnishings, negatively geared real estate, discretionary family trusts and so on.

There are emerging signs of these adjustments in the APRA quarterly performance data on personal contributions and overall net contribution flows into super over recent quarters, shown in the chart on page 11.[10] We can expect considerable turmoil in personal contributions over the next few quarters. For example, couples are likely to rearrange super balances from the high balance partner to the low balance partner in anticipation of the 1 July 2017 cut in concessional and non-concessional contributions. So data for the December quarter 2016, and the March and June Quarters 2017 will be turbulent. We expect that as the numbers settle down after the June quarter 2017, there will be much weaker personal contributions into super.

As the evidence of this damage mounts, quarter by quarter, Parliament will soon have to repair the design flaws introduced by the 2015 Hockey Budget and the 2016 Morrison Budget.[11]

Most of the behavioural adjustment to pension and super changes occurs in the intersection between the pension and superannuation. Treasury modelling suggested many were moving from a full pension and low living standards to higher living standards from a part age pension supplemented by growing lifetime super balances arising from the Guarantee Levy and the Simplified Superannuation measures of 2007.

This decline in the proportion of those age-eligible for the pension receiving a full pension, and the growth in the proportion receiving only a part pension were considerable but understated achievements of the previous pension and super regimes. We doubt that movement will continue under the 2017 policies.

Instability necessitates considered reform to rebuild trust and confidence

The instability introduced into today’s retirement income system has many elements:

- The reintroduction of a severe taper for the pension asset test close to average super balances will damage voluntary contributions to super, reduce overall saving effort and increase popular commitment to the ‘sweet spot’ strategy of saving no more than $340,000 and taking a part-pension. The incentive for those around the ‘sweet spot’ to move beyond that by more saving effort and becoming self-funded retirees has been severely damaged.

- The tighter restrictions on concessional and non-concessional contributions to super also hinder the opportunities to break out of the black hole of high effective marginal tax rates. To move from the optimum ‘sweet spot’ super balance to appreciably higher, self-funded retirement income would require more than doubling the super balance by more than $650,000.

- The lowering of the income cap for concessional contributions beyond which tax is imposed at 30% further hinders the accumulation of larger super balances.

- The Government’s new tax expenditures on super try to encourage those whose lower incomes mean they can’t save much (and perhaps nothing that they can afford to lock away for 40 years in super). What little additional saving does occur into small super balances is unlikely to relieve low-income savers’ dependence on the full age pension. Moreover, the effectiveness of the new incentives for the relatively poor has been damaged by the overall loss of trust in super and super law-making.

- The $1.6 million transfer balance cap and its extremely complicated support structures of Personal Transfer Balance Caps, Transfer Balance Accounts, Total Superannuation Balance Rules, First Year Cap Spaces, Crystallised Reduction Amounts, Excess Transfer Balance Earnings and Excess Transfer Balance Taxes, have directly discouraged high super balances, raised savers’ compliance costs, and increased super funds’ administrative costs. The latter higher costs will flow through to all super savers, further discouraging voluntary inflows into super funds.

Conclusion and way forward

The Government will increasingly experience savers’ and retirees’ criticisms as these new policy distortions bite. The Shepherd Review can play a constructive, leading role in speeding the repair process and rebuilding trust and certainty in the retirement income system through:

- advocating use of appropriate grandfathering provisions in respect of the 2017 measures to contain damage to trust and certainty;

- seeking the release of Government long-term modelling of the effects of the 2017 measures and their replacements, such as was done in 2012 for earlier super and pension policy settings; and

- advocating the implementation of a new way of making better-considered retirement income policy changes. Jeremy Cooper’s 2013 report, A Super Charter: Fewer Changes, Better Outcomes, provides one model of a useful way forward.

[1] Peter Costello, A Plan to Simplify and Streamline Superannuation: Detailed Outline, Canberra, May 2006.

[2] Save Our Super’s submissions to Treasury’s exposure drafts one, two and three of the legislation, and to the first of two inquiries by the Senate Economics Legislation Committee chronicle the absurdly rushed ‘consultation’ processes for all but the last of these five opportunities for comment.

[3] Ken Henry, Treasury’s effectiveness in the current environment, Address to staff, 14 March 2007.

[4] See Section 5 of Save Our Super, Submission on Second Tranche of Superannuation Exposure Drafts, 10 October 2016.

[5] See Treasury website, Retirement Income Modelling.

[6] “Between age pension age and 70, the proportion without a pension will typically exceed 40% but with drawdown in retirement and successive cohorts living longer, the average over all ages is sticky at around 20 per cent.” See George P Rothman, Modelling the Sustainability of Australia’s Retirement Income System, Retirement and Intergenerational Modelling and Analysis Unit, Department of the Treasury, July 2012.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Corbett’s work is reported by Henry Ergas, Who’ll pay for our long lives and pensions?, The Australian, 9 January 2017.

[9] The phrase ‘effective retrospectivty’ was coined by Treasurer Morrison:

“That is why I fear that the approach of taxing in that retirement phase penalises Australians who have put money into superannuation under the current rules – under the deal that they thought was there. It may not be technical retrospectivity but it certainly feels that way. It is effective retrospectivity, the tax technicians and superannuation tax technicians may say differently. But when you just look at it that is the great risk.”

Address to the SMSF 2016 National Conference, Adelaide, 18 February 2016 (emphasis added).

[10] See also Glenda Korporaal, Super shake-up hits fund flows, The Australian, 22 February 2017.

[11] See section 7 of Save our Super’s Submission to the Senate Economics Legislation Committee of 17 November 2016.

Sunday, July 16, 2017

Out of all the whinging, the retrospective whinge is by far my favourite whinge. The golden rule is to highlight the hypocrisy of the whinger. It’s no good debating them on definitional grounds – They’ll never agree. To rebut the whinger who relies on the ‘retrospective’ changes, ask them the following –

Did they make the similar complaint in 2006 when Costello made all outputs from super tax free? Changes to super in 2006 weren’t grandfathered so clearly the changes were ‘retrospective’ in nature. Did the whingers of today whinge then too?

Enjoy the blank stare that lingers from the face of the (now silent) whinger…..