10 October 2016

SUBMISSION ON SECOND TRANCHE OF SUPERANNUATION EXPOSURE DRAFTS

Terrence O’Brien and Jack Hammond QC, on behalf of themselves and Save Our Super

According to Treasurer Scott Morrison:

“One of our key drivers when contemplating potential superannuation reforms is stability and certainty, especially in the retirement phase. That is good for people who are looking 30 years down the track and saying is superannuation a good idea for me? If they are going to change the rules at the other end when you are going to be living off it then it is understandable that they might get spooked out of that as an appropriate channel for their investment. That is why I fear that the approach of taxing in that retirement phase penalises Australians who have put money into superannuation under the current rules – under the deal that they thought was there. It may not be technical retrospectivity but it certainly feels that way. It is effective retrospectivity, the tax technicians and superannuation tax technicians may say differently. But when you just look at it that is the great risk.”

Address to the SMSF 2016 National Conference, Adelaide, 18 February 2016 (emphasis added).

“Now that we have a new PM (Malcolm Turnbull) and new treasurer (Scott Morrison), and newly re-elected Coalition government, anything is possible based on the recent super changes announced in the 2016 Federal Budget.”

Trish Power, SuperGuide: Tax free super for over 60s, except for some, 23 August 2016 (emphasis added).

Declaration of interests: Terrence O’Brien is a retired public servant receiving a super pension from a defined benefit, ‘untaxed’ fund. He would be adversely affected by some of the measures in the second tranche.

Jack Hammond QC is in the process of retiring from his barrister’s practice. He will be adversely affected by some of the measures in the second tranche.

Contents

| 1. | Summary | 2 |

| 2. | Inadequate time for public comment | 6 |

| 3. | Inconsistency of measures with Government’s stated objectives | 6 |

| 4. | Superannuation savers: tax minimizers and estate planners? | 7 |

| 5. | The complexity of the Transfer Balance Caps | 8 |

| 6. | One forgotten benefit of simplicity: compliance costs | 9 |

| 7. | Faulty arguments for reducing super incentives: high cost, unfairness and unsustainability | 11 |

| Cost: measures not fit for purpose | 11 | |

| ‘Fairness’: more dimensions than vertical redistribution alone | 12 | |

| Sustainability: an empty concept for super concessions | 14 | |

| 8. | ‘Effective retrospectivity’ is pervasive throughout the measures | 15 |

| 9. | Super tax increases without grandfathering change the moral landscape | 18 |

| 10. | Is $1.6 million a defensible cap? | 19 |

| 11. | Complexity and risk for the taxpayer: the case for safeguards | 20 |

| 12. | Bereavement | 20 |

| 13. | Treatment of defined benefit retirement income streams | 20 |

| 14. | Lower minimum drawdown amounts on super pensions | 22 |

| 15. | Innovative income streams: more costs of ‘effective retrospectivity’ | 22 |

| 16. | Conclusions | 23 |

1. Summary

The intended measures reverse the strategic direction of the Costello reforms of 2006-07 by circuitously, but in effect, re-imposing tax on retirement incomes — so far, on those self-funded retirees who over decades and under current law have saved more than $1.6 million. It will serve as a precedent for those who favour future increases.

The new measures effectively impose tax on the earnings on superannuation savings over $1.6 million accumulated for up to 40 years and now lawfully in retirement accounts that are tax-free under current law. In over 100 years of Australian superannuation law, no such earnings tax on retirement capital has ever been imposed previously. To enable that tax, the Government proposes a complex new structure of ‘transfer balance accounts’, ‘general transfer balance caps’, ‘personal transfer balance caps’ and ‘excess transfer balance’ taxes to claim that the new earnings tax is not on the ‘retirement phase’ as newly defined, but rather on the redirection of retirement funds into an accumulation account.

Consequent on this unexplained choice of approach, the measures are absurdly complex. In one fell swoop, they more than undo the simplification gains and the administration and compliance cost reductions from the Costello reforms. In 2006, Treasurer Costello took an excessively complex super system which taxed retirement income in up to 8 different parts in 7 different ways, and simplified it to today’s system. Reducing previous super earnings taxation complexity down to today’s comparative simplicity took 144 paragraphs in the 2006 Explanatory Memorandum. In 2016, Treasurer Morrison’s re-complication of the taxation of retirement income — just one chapter of the Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials on the transfer balance cap — takes 269 paragraphs, almost 90% longer.

Given the complexity and pervasive effects of the changes, the 13 days allowed for public consultation on some 234 pages of material is derisory. Treasurer Costello’s reforms provided a 4 month window for comment, and garnered some 1,500 written submissions. (In the little time available, this submission has only scratched the surface of the first chapter and part of the eighth chapter of the 10 chapter Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials.)

The Government should provide a statement (as is soon to be mandatory under its own first tranche legislation) on the consistency or otherwise of the proposed measures with its objectives for superannuation. Those objectives, we are told, are ‘to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the age pension’, and five subordinate objectives, one of which is to ‘be simple, efficient and provide safeguards’. The Government statement should also include quantification of the compatibility of the measures with its own stated objectives, with particular attention to the combined effect on super and age pension cost, levels of self-sufficiency in retirement and retirement living standards.

A statement of consistency with objectives would test both the validity of the proposed measures, and the practicality of the stated objectives. Before changing the super law, a key issue to enumerate in a transparent and quantified manner is whether the total impact over time of all the measures reduces government costs of the retirement system in net terms, or (as seems likely) worsens the budget position over time through destroying confidence in super and increasing resort to the age pension. The destruction of confidence arises through the announcement of tax increases of a type that Treasurer Morrison called ‘effectively retrospective’ and the abandonment of customary grandfathering.[i]

The measures are ‘effectively retrospective’ in that they re-assign pension account capital whose earnings are now lawfully tax-free. If transferred to an accumulation account they will be taxed. The measures thus instantly reduce the living standards of some who have already retired, and who have only trusted their life savings to super because of the protection of the current tax laws. The measures also blindside those too close to retirement to change their legitimate saving plans. The measures adversely affecting these groups should be appropriately grandfathered.

Grandfathering in such cases has been the sound practice of all governments for all other significant super tax increases over at least the last 40 years. Grandfathering is necessary to preserve trust in super and in future law-making for super.

If grandfathering is abandoned, it alters the moral landscape of obedience to taxation law and reduces the legitimacy citizens vest in government.

None of the Government documents on its measures mention compliance costs, still less enumerates them. Contrary to repeated claims that 96% (or 99%) of individuals with superannuation will either be better off or unaffected as a result of the changes, every super saver who seeks to access significant life savings in the retirement phase will be adversely affected by having to create a transfer balance account and to monitor their position relative to a general transfer balance cap and their personal transfer balance cap.

Costly professional financial advice will again become essential at every superannuation decision point. Total additional compliance costs imposed on super savers will be very large. For Self-Managed Super Funds alone, they could easily total $1.5 to $2 billion in 2017, with lesser recurrent costs annually thereafter.

The Government states as reasons for its measures the allegedly high cost of existing concessions, unfairness in their distribution, and ‘unsustainability’ over time. All three claims are strongly disputed, and should be reexamined objectively.

The tax increases take effect when global growth prospects are poor and falling, and many interest rates are near-zero or negative in real terms. Self-funded retirees now face an era of ‘return-free risk’, so the increase in complexity, compliance cost and taxes is particularly badly timed.

By far the greatest complexity (and much of the ‘effective retrospectivity’) in the second tranche arises from the transfer balance account concept, the transfer balance caps and their associated provisions. It has never been explained why that approach is desirable, and why such complexity is necessary.

The transfer caps and associated measures give draconian powers to the Taxation Commissioner, and impose heavy penalties on taxpayers who may be defeated by the complexity of the measures. If the measures proceed, Parliament should require the Commissioner to provide a safeguard to all savers with personal transfer balances over $500,000 by issuing binding advance statements of their transfer cap position well before the starting date of the measures, and with timely notification every year thereafter.

The proposed increased taxes on defined benefit pensions are amongst the most complex parts of the measures. Their many components make it impossible to judge whether their combined impact is more or less commensurate with the increased taxes on self-funded retirees with high transfer balances. Almost all defined benefit schemes have long been closed to closed to new entrants. If the Government grandfathered its policy to increase tax on those already retired and receiving tax-free benefits from taxed funds with assets above $1.6 million supporting their pensions, it would be unnecessary to grapple with the ‘broadly commensurate’ treatment of defined benefit schemes.

The Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials introduces a novel idea: to extend the earnings tax exemption that the Budget removes from current retirement income streams arising from a transfer balance cap above $1.6 million. The extended concession would apply to innovative lifetime products such as ‘deferred products’ and ‘group self-annuities’ that may emerge in the future. But absent grandfathering on current tax increases, why would anyone embrace new products with even longer vulnerability to future policy change?

Public consultations to date on these complex matters have been manifestly inadequate, If the proposed legislation is passed by the House of Representatives, the Senate should subject it to careful scrutiny. It should refer the whole of the Government’s proposed superannuation package to a Senate Committee. The Senate Committee should invite and consider public submissions and objections. The assumptions which underpin the changes should be open to public challenge.

The government should go back to the drawing board on its measures. If, having reviewed the weak basis of claims about the cost, unfairness and unsustainability of super concessions, the Government still wants to raise more revenue from self-funded retirees, it should do so more fairly by appropriate grandfathering.

2. Inadequate time for public comment

For this second tranche of legislation as for the first tranche, the time allowed for consultation is derisorily short. Self-funded retirees and savers with vital interests in the superannuation system have been given just 13 days to consider 234 pages, 57,600 words of very complex, far-reaching proposed legislation. That makes a mockery of the concept of public consultation. In at least two specific and very technical areas, complex matters that have defeated policy advisers, super industry and financial advisors over four months have been flicked to the general public on an impossibly short timetable.[ii] More draft legislation and explanatory material is still to be released.

In the limited time available, this submission focusses just on the Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials for the second tranche, and mostly on just Chapter 1, the 66 page explanation of the transfer balance cap at the heart of the tax increases. The other 9 Chapters of the Explanatory Materials await proper consultation opportunities in the future, such as before a Senate Committee.

Australian super lawmaking processes have deteriorated to the cost of public confidence in super. Contrast the current exercise with the planning for and consultation around the last major change of strategic direction in Australian super law, the Costello Super Simplification exercise of 2006 and 2007.[iii] A substantial discussion paper was issued with the May 2006 Budget announcement of the measures, with an extended consultation over four months until September 2006.[iv] There was keen interest to comment: more than 1,500 written submissions and more than 3,500 phone calls from across the community.

3. Inconsistency of measures with Government’s stated objectives

The Government claims its measures have been guided by its soon-to-be-legislated primary objective for superannuation,

.. to provide income in retirement that substitute or supplements the age pension.[v]

What does that mean? Would a policy change be considered successful if it discouraged super savers from achieving higher savings balances and created uncertainty and costs for future super savings, while encouraging reliance on the super guarantee levy and topping up retirement income with a part pension? That reduction in self-reliance seems to be the likely effect of the proposed measures. The Government also specifies 5 subordinate objectives which include “be simple, efficient and provide safeguards”, to be traded off against each other and balanced against the principal objective using unspecified processes and weights. [vi]

Compare those bewilderingly ambiguous objectives with the Howard-Costello era objective for superannuation simplification:

The policy objective is to assist and encourage people to achieve a higher standard of living in retirement than would be possible from the age pension alone.[vii]

Or another possibility, suggested by the Institute of Public Affairs:

The objective of the superannuation system is to ensure that as many Australians as possible take personal responsibility to save for their own retirement. The age pension provides a safety net for those who are unable to provide for themselves in retirement.[viii]

Terrence O’Brien has argued in his submission to Treasury of 16 September 2016 on the first tranche of measures (which includes the legislation to state the Government objectives above) that the Government’s six objectives are, in practice, meaningless and unworkable. We favour adopting the IPA’s suggested alternative.[ix] But the Government’s six proposed objectives should at least be tested with the current superannuation proposals. The Government should provide a quantified statement showing the compatibility of the measures with its own stated objectives, as will become compulsory from 2017 if the Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016 becomes law.

There will be four major impacts of the first and second tranche measures.

First, they will reduce super self-reliance and increase reliance on the age pension: For example, Tony Negline illustrates that for a married couple there is severely diminishing returns from saving more than about $340,000 in super, as that amount maximizes the combined retirement income from a super pension and a part age pension. One could save almost 5 times more to reach the super target of $1.6 million and only gain a little more than twice the retirement income.[x] The Government’s measures to induce saving above $1.6 million back into the accumulation phase paying 15% tax will further weight the trade-off against self-reliance and saving in super. Negline concludes the best strategy is to save in super only the mimimum required by the super guarantee levy and to invest in the best (and best maintained) home one can afford.

Second, they will reduce trust in superannuation as a safe vehicle for lifetime savings and a secure living standard in self-funded retirement: Terrence O’Brien’s report for the Centre for Independent Studies, Grandfathering super tax increases, explains how the Government’s proposed approach breaches at least 40 years of good practice in grandfathering super tax increases and will severely damage confidence in super saving.[xi]

Third, they will increase resort to investment outside superannuation, for example in negatively geared property as well as the incentive to invest in the principal residence noted above.[xii]

Finally, as a consequence of the foregoing point, they will decrease the efficient allocation of scarce savings through efficient capital markets. [xiii]

4. Superannuation savers: tax minimizers and estate planners?

The Government has argued that its measures seek to “reduce the extent to which superannuation is used for tax minimization and estate planning.” (e.g. Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and sustainable superannuation) Bill 2016: Exposure draft explanatory materials, p 8 para 1.6)

It is hard to make sense of this claim.

Because of the disincentive to long-term saving from a progressive tax on nominal income, the existence of a generous age pension, and the 40-year restriction on access to super savings, for over 100 years governments have used tax incentives to support superannuation. In responding to those deliberate incentives as Parliament intended, anybody who has a superannuation account is in a sense a ‘tax minimizer’.

Most have thought (since at least Menzies’ Forgotten People speech of 1942[xiv]) that the purpose of super tax incentives was to encourage thrift and self-reliance. Worse things can happen to a country than its workers practice thrift and save for their own retirement, with any excess for their children’s benefit.

Referring to super savers as tax minimizers and estate planners is not a guide sound policy analysis or good policy.

5. The complexity of the Transfer Balance Caps

The Government documentation nowhere explains why the objective of raising more revenue from some self-funded retirees and from those saving to become self-funded, requires the inevitably complex and ‘effectively retrospective’ approach of:

- moving funds already lawfully placed in a retirement account into a new transfer balance account, and

- forcing any excess in the transfer balance account over $1.6 million into an ‘accumulation account’ and taxing the income on that account at 15%.

It is helpful to look below the surface to the reality of the measures. On the surface, the Government argues that there is no real change in the measure: 96% (or 99%) will be better off or unaffected under all the Budget measures, saved capital is preserved, funds are left inside superannuation framework, etc.[xv] But the reality is that the measure reduces living standards from lifetime savings made under existing law and already funding retirement free of tax (if from a taxed fund); under the new law it reduces the retiree’s living standard by subjecting any ‘excess’ savings over the transfer balance cap to 15% tax on earnings, and without grandfathering.

This new tax on fund earnings within the retirement phase is unprecedented in over 100 years of specific Australian taxation measures governing superannuation.[xvi]

The additional tax has the simple effect of reducing retirement income by an ‘effectively retrospective’ change in the law.

The specific means for applying the transfer balance account through general and personal transfer balance caps quickly turns inevitable complexity into absurd complexity.

When the Costello simplification measures were legislated in 2006, the Explanatory Memorandum explained the full gamut of the new taxation of retirement income streams in just 144 paragraphs, most devoted to mapping the previous law’s complicated treatments into the current streamlined treatments under the laws within which retirees have now organized their savings.[xvii]

The new proposed treatment of retirement income takes 269 paragraphs of attempted explanation in the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016: Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials, with several acknowledgements that complex areas have yet to be settled and seeking further public input (though obviously not within the time frame given for consultation).

So it is taking Treasurer Morrison about 90% more verbiage to explain the re-complication of the taxation of retirement income as it took Treasurer Costello to explain simplification of the status quo ante.

6. One forgotten benefit of simplicity: compliance costs

Key Government measures in the second tranche reverse the strategic direction of the 2006-2007 Howard-Costello superannuation simplification reforms by reintroducing, in effect, the taxation of end benefits.

If the second tranche were implemented, it would reintroduce such complexity in superannuation law that the superannuation tax structure would be returned in one fell swoop to a worse state than immediately before the Howard-Costello reforms. With such complexity, introduced with limited time for consultation, comes the high risk of unforeseen consequences and the need for further legislative changes in future, presently unforeseeable as to detail. This risk is a further cloud over the credibility of super as a repository of life savings and a foundation for self-funded retirement.

Since the lessons of even a decade ago are now apparently lost, it is worth remembering the recent experience of complexity in superannuation end-benefit taxation:

The report of the “Taskforce on Reducing Regulatory Burdens on Business, Rethinking Regulation”, recommended that high priority be given to comprehensive simplification of the tax rules for superannuation benefits. The report highlighted that the greatest area of complexity is the taxation of end-benefits.Superannuation benefits tax is by far the most complicated and is the tax that individuals must confront when entering or contemplating retirement. At present, it is difficult for anyone to understand how their superannuation benefits will be taxed.A lump sum may include up to eight different parts taxed in seven different ways.The complexity of the benefits tax arrangements not only affects retirees. It affects individual decisions concerning additional superannuation contributions. It also adds to the administration costs of superannuation funds.[xviii]

The Government has repeatedly claimed that 96% (or sometimes, 99%) of individuals with superannuation will either be better off or unaffected as a result of the changes.

The reality is that every potential self-funded retiree who one day seeks to enter the superannuation retirement phase will be adversely affected by the complexity and compliance costs of creating transfer balance accounts and monitoring their saving relative to the general transfer balance cap and the evolution of their personal transfer balance cap. Costly professional financial advice will again be essential at every superannuation decision point.

The administration costs for the Australian Taxation Office provide one illustration of the complexity of the approach, with a Budget allowance of $4.4 million in 2016-17 to prepare for the transfer balance cap and associated measures.[xix] But the administrative costs pale in comparison to the compliance costs imposed on savers and retirees. Compliance costs are nowhere mentioned, let alone quantified, in the Government’s documentation.

What might be the order of magnitude of compliance costs? Let’s assume, for the sake of illustration, that all 557,000 self-managed super funds need to seek financial advice on the impact of the new measures by 30 June 2017.[xx] The compliance costs for SMSFs are estimated to be $3000-$4000 per fund. [xxi] The total extra cost for SMSFs in 2017 could be of the order of $1.5 to $2 billion dollars.

There are also 14.8 million individual Australians with super accounts. If we assume fund members aged 50 or older and with appreciable super savings similarly seek advice, and that the simpler issues raised for super fund members cost $300-$600 in professional advice, that might add another $0.5 billion to the advice costs incurred by SMSFs.

Of course to that should be added the costs to savers and retirees themselves of providing the organized information on their affairs necessary for financial advisers to ply their trade.[xxii] Depending on the valuation of taxpayers’ time, that could easily add another 25% or more to arrive at a total compliance cost.

Taxpayers who may be affected by the tax increases and super restrictions should certainly seek financial advice before 30 June 2017. Even assuming the availability of professional advice in the face of a very large surge in demand, it will be difficult for the large numbers of people with multiple super accounts to obtain a consolidated statement of their exposure to the transfer balance caps in time for the intended initiation of the tax increases. (Over 40% of the 14.8 million super savers have more than one account; 8% have four or more.)

While for many, actions will be required by 30 June 2017 or urgently within a few months thereafter, there will likely be continuing compliance costs and the need to seek financial advice – in some cases (such as SMSFs, or those near their personal balance caps) perhaps year by year. In other cases, recurrent compliance costs may be less frequent. But the annual compliance costs in perpetuity will certainly be non-trivial, and vastly exceed the benchmark achieved after the Costello simplification reforms.

Let’s estimate, conservatively, that total initial compliance costs amount to $2 billion in 2016-17, and another $1 billion in 2017-18. These numbers may be scaled against the Budget measures which are said to raise less that $6 billion gross over the forward estimates to 2019-20. In net terms after creation of the new tax expenditures on super in the tranche one measures, the net revenue gain to 2019-20 was said to be less than $3 billion.

So on conservative estimates, the net revenue gains from the Budget measures over 4 years would be roughly equalled by the initial compliance costs to savers and retirees. Of course, our estimates of compliance costs are just a first attempt to scale the problem. Parliament should require the Government to produce explicit, transparent, official estimates of the compliance costs of the measures.

All these administrative and compliance costs are being generated in a legislative package that includes the Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016, whose explanatory material adds that among five supplementary objectives to the primary objective (“to provide income in retirement to substitute or supplement the age pension”), one that requires that the system should “be simple, efficient and provide safeguards”.[xxiii]

7. Faulty arguments for reducing super incentives: high cost, unfairness and unsustainability

The Government claims the second tranche measures (and indeed the first tranche measures) are all necessary to make super tax treatment less expensive to revenue, more sustainable and fairer — indeed, “even fairer” than initially proposed.[xxiv] Those claims have never been properly evidenced or enumerated. A Senate Committee inquiry would enable those claims to be tested.

Cost: measures not fit for purpose

The foundation of the argument for reducing super concessions is their allegedly excessive total cost. However super tax incentives are not give-aways. As expressed in the 2009 Henry Review, Australia’s future tax system:

The essential reason for exempting lifetime savings or taxing them at a lower rate is that income taxation creates a bias against savings. The income taxation of savings therefore discriminates against taxpayers who save. They pay a higher lifetime tax bill than people with similar earnings who choose to save less. As savings can be thought of as deferred consumption, the longer the person saves and reinvests, the greater the implicit tax on future consumption …… For a person who works today and saves, taxing savings also reduces the benefit from working.The increasing implicit tax on future consumption provides an argument to tax longer-term lifetime savings at a lower rate. An individual can undertake lifetime saving through a variety of savings vehicles, but there are asset types that are more conducive or related to lifetime savings: namely superannuation and owner-occupied housing.[xxv]

That distortion is exacerbated by the provision of an aged pension with a generous income and asset tests:

Pension costs as a percentage of wages are at the highest level they have ever been, having nearly doubled over the past 40 years The means test has become much more generous: the upper limit of the assets was just under 12 times the full rate of the pension in 1911, whereas today the ratio between the single homeowner assets test cutoff is nearly 35 times the full rate (despite the massive increase in the full rate of the pension over that time).[xxvi]

Long-term saving such as superannuation would be non-existent without extensive tax incentives.

However as the Treasurer has noted the annual (gross) tax expenditures on super may be $30 billion, or they may be $11 billion.[xxvii] Indeed, according to separate studies by Ken Henry and Jeremy Cooper, they may be less still in gross terms, and less again (or even a net budget benefit) once the impact on age pension uptake is considered. As Robert Carling of the Centre for Independent Studies has argued,

Statements often made about the huge fiscal cost of Australia’s superannuation tax concessions are based on the comprehensive income tax benchmark for measuring tax expenditures, but the characteristics of superannuation make it unsuitable for such a benchmark. The most appropriate benchmark is an expenditure tax under which contributions and fund earnings would be tax-exempt but end-benefits fully taxed. When measured against such a benchmark, tax expenditure on superannuation is much lower than commonly believed, or non-existent.[xxviii]

‘Fairness’: more dimensions than vertical redistribution alone

The Treasurer has noted that the top deciles of taxpayers get the most benefit from tax incentives to save in superannuation; this may be called the ‘Duncan Storrar effect’.[xxix]

You all know high-income earners generally have far more capacity, and inclination, to save for retirement. This is a good thing, this is a very good thing, it’s not something that should be demonised or seen as some sort of nefarious practice. Which is, I think, often a point that is implied when people make criticisms of these things. I think it is great that people are out there saving for their own future. I think it is tremendous.[xxx]

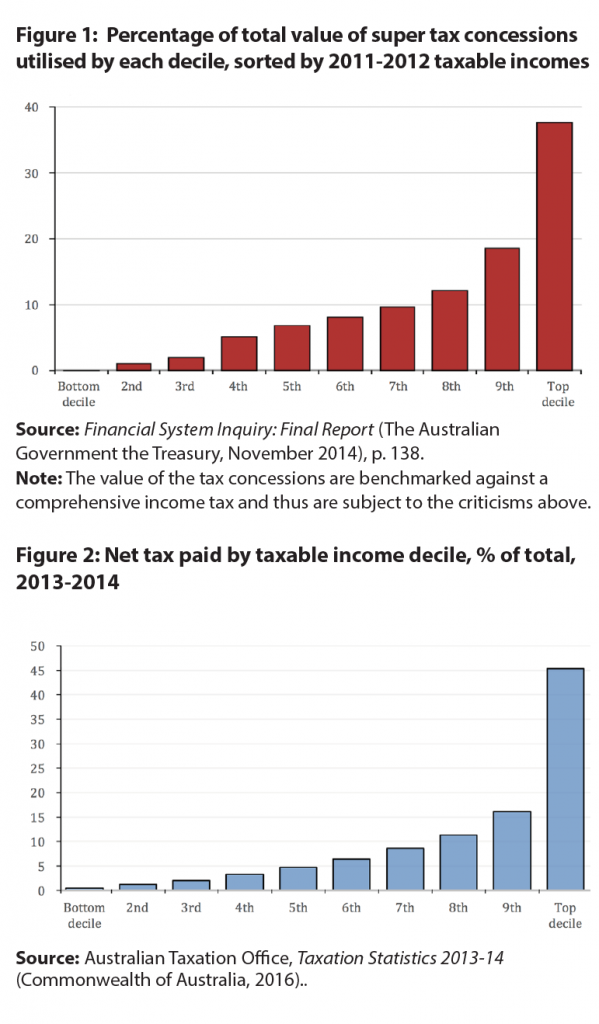

It has fallen to the CIS’s Robert Carling to illustrate that the greater utilization of super tax concessions by the relatively rich – usually reported without any context, as if a self-evident scandal – is roughly proportionate to the contributions of each decile to the income tax take (see charts on following page).[xxxi] Indeed, the richest 10 per cent utilize somewhat less than ‘their share’ of the super concessions.

There is also a mistaken tendency to regard ‘fairness’ as a one-dimensional concept requiring nothing more than vertical redistribution from the relatively rich to the relatively poor. This often seems to be pursued without any logical limit short of perfect equality, and disregarding other dimensions of fairness made worse along the way. In this common view, it is not sufficient merely to maintain Australia’s existing progressive tax/benefit system, even though in comparison with other OECD economies, both tax and benefits components of the system are highly progressive. [xxxii]  In contrast to this one dimensional view of fairness as no more than vertical redistribution, most Australians understand that fairness is a multi-dimensional concept. It is certainly fair that we as individual and as a community provide for the indigent. But equally importantly, it is also fair that those who work hardest and bear the greatest risks in economic life should gain the greatest reward after paying their lawfully imposed taxes. It is fair that far-sightedness in providing for the future is rewarded. It is fair that thrift is rewarded. Nor are all dimensions of fairness positive; fairness can have elements of disapprobation: for example, many feel that the feckless or those unwilling to work should not be able to free-ride on their more industrious fellow citizens. Finally, most consider it fair that people — and governments — should honour their commitments.

In contrast to this one dimensional view of fairness as no more than vertical redistribution, most Australians understand that fairness is a multi-dimensional concept. It is certainly fair that we as individual and as a community provide for the indigent. But equally importantly, it is also fair that those who work hardest and bear the greatest risks in economic life should gain the greatest reward after paying their lawfully imposed taxes. It is fair that far-sightedness in providing for the future is rewarded. It is fair that thrift is rewarded. Nor are all dimensions of fairness positive; fairness can have elements of disapprobation: for example, many feel that the feckless or those unwilling to work should not be able to free-ride on their more industrious fellow citizens. Finally, most consider it fair that people — and governments — should honour their commitments.

It is these broader concepts of fairness that explain why so many are critical of the Government’s claim that it is fair to reduce by ‘effectively retrospective’ tax increases the living standards of those self-funded retirees who have responded as governments have intended to incentives to save in super. They are equally critical of the Government’s intent to restrict, without time to adjust, the savings in super of those older workers too close to retirement to change their life savings plans.

Sustainability: an empty concept for super concessions

There has been no discussion of what the notion of ‘sustainability’ might mean in the case of the Costello-era simplification of super taxation that levied tax at the contribution and accumulation stage of superannuation, but allowed retirees over 60 who had contributed to taxed funds, untouchable during their working lives, to draw down their savings in retirement without further taxation. (This is the same model as for the taxation of bank account savings – no one thinks that if they need to withdraw $100 from an ATM, they should receive less than that because of a third stage of taxation.)

Of course, if people save more in super and pay more super contributions tax (as they have been doing, following Government compulsion or incentives), then they will earn more in the accumulation phase (and pay still more tax on that income). Finally, they will enjoy higher super balances in retirement. In what sense does the lack of a third stage of taxation on higher retirement balances become ‘unsustainable’ as the amount of super savings rise? Would it be argued that the taxation treatment of bank account savings has become unsustainable as bank accounts have grown?

The costing of the Costello simplification reforms was part of a well-considered and consultative process. In the 2006-07 Budget documentation the costs of the super concessions were estimated over the forward estimates period, and those estimates were refined again on the release of the final simplification measures. There is no evidence the subsequent evolution of the costs of super concessions, properly benchmarked, has been in any sense unanticipated.

8. ‘Effective retrospectivity’ is pervasive throughout the measures

If there were no concessional taxation arrangements for superannuation, the current system would not exist. A progressive tax on nominal income and a generous age pension heavily penalise long-term saving, and there is no longer and more restricted form of long-term saving than superannuation. A saver’s consumption is locked away over some 40 years of a working life, and must then sustain living standards for some 30 year thereafter.[xxxiii]

The tax treatment of super is specified in law over all three stages of the super life cycle: contributions, accumulation and retirement. Savers penalised by the Budget measures would not have accumulated such high balances locked untouchably into superannuation if they had had foreknowledge of how the tax treatment in the retirement phase would be increased after they had retired.

The Budget measures are not just changing the rules after the game has started; they are changing them well into the fourth quarter. That is the context in which Treasurer Morrison coined the useful term ‘effective retrospectivity’:

One of our key drivers when contemplating potential superannuation reforms is stability and certainty, especially in the retirement phase. That is good for people who are looking 30 years down the track and saying is superannuation a good idea for me? If they are going to change the rules at the other end when you are going to be living off it then it is understandable that they might get spooked out of that as an appropriate channel for their investment. That is why I fear that the approach of taxing in that retirement phase penalises Australians who have put money into superannuation under the current rules – under the deal that they thought was there. It may not be technical retrospectivity but it certainly feels that way. It is effective retrospectivity, the tax technicians and superannuation tax technicians may say differently. But when you just look at it that is the great risk. (Emphasis added.)[xxxiv]

Because of the typical 40-year length of commitment to making super contributions and the unique restrictions on accessing super savings, people need a lengthy adjustment period to respond to any adverse changes to policy. The same is true of the closely related issue of age pension changes. That is why past successful significant changes to retirement parameters – such as the means test of the age pension, the pension eligibility age, the superannuation preservation age or increased taxation of superannuation – have generally been undertaken gradually, with advance notice, extended consultation and often with ‘grandfathering’ of existing arrangements to prevent disadvantaging workers close to retirement, or retirees who have limited or no opportunity to change their lifetime savings strategies.

To induce savers to lock away savings on the basis of an existing tax package over all three stages and then to raise tax on those already retired or too close to retirement to change their savings plans, not only reduces the living standards of those directly affected; it also destroys every saver’s trust in super (and in government law-making). That in turn reduces everybody’s preparedness to risk unpredictable future legislative penalties on self-funded retirement, and increases the risk-management attractions of blending lower super balances with more reliance on the age part-pension.

The challenges of facilitating gradual increases in super taxes while not destroying confidence in super were addressed most thoughtfully by the late Justice Kenneth Asprey, who was commissioned by the outgoing McMahon Government to report on the Australian taxation system. Asprey made his Committee’s final report to the Whitlam Government. His recommendations at first had little apparent effect, but it they drove all the major advances in Australian tax reform over the following quarter century:

The capital gains tax, the fringe benefits tax, dividend imputation, the foreign tax credit system, the goods and services tax (he called it a “broad-based value-added tax”) — all were proposed in the Asprey report.[xxxv]

The Asprey insights into the need to grandfather super tax increases, and his principles for how to do that while preserving necessary policy flexibility to respond to changing circumstances are shown in the following Box.

More recently, the Gillard Government’s Superannuation Charter Group led by Jeremy Cooper addressed concerns about the future of the super savings and the way policy changes have been made.[xxxvi] The Charter Group reported to the second Rudd Government in July 2013 with useful proposals in the nature of a ‘superannuation constitution’ that would codify the nature of the compact between governments and savers, including:

- In order to promote confidence in the long-term benefits, no change to superannuation should be regarded as urgent.

- People should have sufficient confidence in the regulatory settings and their evolution to trust their savings to superannuation, including making voluntary contributions.

- Relevant considerations, when assessing policy against the principle of certainty, include the ability for people to plan for retirement and adjust to superannuation policy changes with confidence.

- People should have sufficient time to alter their arrangements in response to proposed policy changes, particularly those people nearing retirement who have made long-term plans on the basis of the existing settings.

Box: Grandfathering principles: Asprey Taxation Review, Chapter 21, 1975

Principle 1

21.9. Finally, and most importantly, it must be borne in mind that the matters with which the Committee is here dealing involve long-term commitments entered into by taxpayers on the basis of the existing taxation structure. It would be unfair to such persons if a significantly different taxation structure were to be introduced without adequate and reasonable transitional arrangements. ………

Principle 2

21.61. …..Many people, particularly those nearing retirement, have made their plans for the future on the assumption that the amounts they receive on retirement would continue to be taxed on the present basis. The legitimate expectations of such people deserve the utmost consideration. To change suddenly to a harsher basis of taxing such receipts would generate justifiable complaints that the legislation was retrospective in nature, since the amounts concerned would normally have accrued over a considerable period—possibly over the entire working life of the person concerned. …..

Principle 3

21.64. There is nonetheless a limit to the extent to which concern over such retrospectivity can be allowed to influence recommendations for a fundamental change in the tax structure. Pushed to its extreme such an argument leads to a legislative straitjacket where it is impossible to make changes to any revenue law for fear of disadvantaging those who have made their plans on the basis of the existing legislation. …..

Principle 4

21.81. …. [I]t is necessary to distinguish legitimate expectations from mere hopes. A person who is one day from retirement obviously has a legitimate expectation that his retiring allowance or superannuation benefit which may have accrued over forty years or more will be accorded the present treatment. On the other hand, it is unrealistic and unnecessary to give much weight to the expectations of the twenty-year-old as to the tax treatment of his ultimate retirement benefits.

Principle 5

21.82. In theory the approach might be that only amounts which can be regarded as accruing after the date of the legislation should be subject to the new treatment. This would prevent radically different treatment of the man who retires one day after that date and the man who retires one day before. It would also largely remove any complaints about retroactivity in the new legislation ….

These Charter Group suggestions would also appear to support the use of grandfathering in the case of the Government’s proposed tax increases. It observed:The Charter Group has formed the view that it is changes to tax concessions and entitlements (for example, to the preservation age or the ability to access super) that are most likely to affect member confidence and call for the additional processes and protections proposed by the Charter.[xxxvii] (emphasis added)

Further details showing how grandfathering adverse changes to superannuation and related retirement income parameters has been used over the last 40 years are contained in Terrence O’Brien’s paper for the Centre for Independent Studies, Grandfathering super tax increases.[xxxviii]

9. Super tax increases without grandfathering change the moral landscape

Ultimately, citizens do not pay tax only because the law says they must. Greek laws say Greeks must pay tax, but many don’t. Russian laws say Russians must pay tax, but many don’t.

Ultimately, citizens in a functioning democracy pay tax because they believe their democratically elected government has legitimacy, and its laws should be respected.[xxxix] Citizens expect governments to be bound by their own laws, just as those laws bind citizens.

‘Effectively retrospective’ changes in super tax laws alter the moral landscape. If a Government passes laws to encourage lifetime savings to be locked in to super, but then changes the rules to suit its budget needs to the detriment of those who relied and acted on the basis of the existing laws, that sends citizens a message: government will change the law with ‘effective retrospectivity’ to the citizen’s disadvantage whenever it wants to.

How is the citizen to respond? Most likely, citizens will be less likely to concede legitimacy to the Government’s new laws. In a world where citizens can lawfully form discretionary family trusts, buy and equip more expensive principal residences, negatively gear rental property and make other adjustments which lawfully minimize their tax, they will be more inclined to do so under the changed laws than if the Government had honoured the laws it had passed, or grandfathered any changes in them adverse to citizens who had relied on, and acted on, the then-current law.

For these reasons, the estimated revenue gains from the tranche two measure are grossly overstated.[xl] Some funds will be removed from super rather than suffer the new tax, and they will not move as Treasury assumes to higher-taxed investments. Rather, they will be spent or move to equally low- or lower-taxed alternatives.

By far the worse damage, however, is not to revenue estimates. It is to trust in the Australian superannuation system, trust in government and ultimately to the idea of government legitimacy.

10. Is $1.6 million a defensible cap?

While the key question about the transfer balance cap is ‘why have it at all?’, many are concerned about its level.

While $1.6 million is a lot of money to many, that mainly reflects unawareness of the actuarial cost of sustaining a reasonable income over some 30 or more years of retirement. Jeremy Cooper has estimated that the actuarial value of the aged pension for a married couple is over $1 million.

The brutal reality is a fair price for an age pension in today’s interest rate environment is about $1 million. For that amount, a couple will get $1297 a fortnight, or $33,717 of income a year. That’s right; the full age pension (including supplements) would cost a 65-year-old couple a surprising $1,022,000 to buy today. For a 65-year old single woman, an age pension-equivalent income stream of $860 a fortnight for life, including supplements, or $22,365 a year, would cost $666,000.An important point to remember is the age pension is a safety net for those without the means to support themselves with dignity in retirement. A comfortable retirement would cost more.[xli]

With lower interest rates today and in prospect, the actuarial cost of the aged pension would be higher than Cooper’s 2015 million dollar estimate. That is for a modest retirement income standard, but one indexed against inflation, protected from the ‘longevity risk’ that one might outlive one’s savings, conferring a range of valuable fringe benefits, and enjoying relatively strong political protection against un-grandfathered future reductions.

In contrast, the self-funded retiree has to save to offset longevity risk, probably low market returns, inflation, and the now considerable risk of future un-grandfathered tax increases. A couple retiring today at age 65 with $1.6 million between them can expect an indexed annual retirement income of some $72,700 (from age 65 until age 100, with part pension from age 82, assuming an optimistic 5% return net of fees and 3% inflation).[xlii] This is about 90% of average weekly earnings. To retire on AWE hardly seems an indecent aspiration, especially if it motivates those who are hard working and thrifty to forgo easier aspirations to rely on a part age pension.

As mentioned above, Tony Negline illustrates that for a married couple there is severely diminishing returns from saving more than about $340,000 in super, as that amount maximizes the combined retirement income from a super pension and a part age pension. One could save almost 5 times more to reach the super target of $1.6 million and only gain a little more than twice the retirement income.[xliii] The Government’s measures to force saving above $1.6 million back into the accumulation phase paying 15% tax will further weight the trade-off against self-reliance and saving in super.

11. Complexity and risk for the taxpayer: the case for safeguards

The exposure draft explanatory materials note that the concept of the ‘retirement phase’ of super is colloquially well established, but now will be formally re-defined and incorporated into the taxation law.[xliv] Unfortunately, this change causes huge complexity and uncertainty, violating the sixth of the Government’s stated objectives for super.

The Commissioner of Taxation is empowered to exercise draconian powers to compel super funds to reduce the saver’s lawfully-established retirement living standards by moving a saver’s funds from a retirement account to an accumulation account. After an initial grace period, the Commissioner can apply severe penalties in the form of an excess transfer balance tax of up to 30% on anyone over their personal transfer balance limit. The revenue assumes notional earnings on any excess transfer balance of the daily interest of the 90-day bank bill yield plus 7 percentage points, compounding daily. Penalty taxes will be based on that formula. Compare that with what super accounts actually earn in the era where savers face ‘return-free risk’. Compare it too with the general advice to self-funded retirees that their portfolios should be low risk and oriented to fixed interest instruments (now yielding about zero real return, and in increasing cases overseas, negative nominal rates, rather than growth).[xlv]

Any well-informed and cautious taxpayer with superannuation incomes from more than one source in retirement and making a close reading of draft would be left mystified as to what his or her personal transfer balance might actually be. (Some 40% of super savers have more than one account, and 8% have more than four.) In one passing acknowledgment of the complexity, the Bill specifies that excess transfer balance tax cannot be self-assessed.[xlvi]

Legislation should require the Commissioner to issue to each retired person in receipt of superannuation income a legally binding statement of their personal transfer balance cap six months before the legislation comes into effect, and six months before the end of every financial year thereafter. Otherwise there is an indefensible imbalance of risk and cost between the revenue and the taxpayer: the Government can make up new laws with any degree of complexity, uncertainty and compliance cost, and the taxpayer bears the risk of trying to comply with them.

Proposed treatment of reversionary super streams on death of one partner are complex and unfair to the bereaved party. [xlvii] It is unrealistic to believe a 6 month decision time after a partner’s death is sufficient, as would be clear to anyone who had ever experienced the time taken to secure probate on even a simple deceased estate.

13. Treatment of defined benefit retirement income streams

The proposed increased taxes on various types of defined benefit schemes to achieve ‘broadly commensurate treatment’ with other tax increases on high balances in other funds is one of the most complex areas of the proposed measures.

The proposals try to grapple with the many historical varieties of defined benefit schemes, most (but not all) unfunded by contributions from the (mostly) government employers that set up such schemes in the medium to distant past. The schemes have generally restricted opportunities to commute pensions into lump sums – ie, they are oriented to providing whole-of-life retirement income rather than the big world tour, which many critics seem to resent. This fact (and the fact that they are unfunded by governments) means they are not amenable to the Government’s preferred approach of forcing assets over $1.6 million supporting retirement income back into an accumulation account. When tax-paid super pensions paid to the over-60s were made tax-free in the 2005 Costello simplification, defined benefit pensions were made taxable at full marginal rates on the whole pension, reduced by a 10% tax offset.

Almost all defined benefit ‘untaxed’ schemes were closed to new members some time ago (a quarter century ago, in the case of the CSS and over a decade ago in the case of the PSS).[xlviii]

If the Government grandfathered its policy to increase tax on those already retired and receiving tax-free benefits from taxed funds with assets above $1.6 million supporting their pensions, it would be unnecessary to grapple with the ‘broadly commensurate’ treatment of defined benefit schemes. Grandfathering the Budget measures on taxed funds would remove the complex issue of how to treat defined benefit schemes – the issue would die away with the defined benefit scheme’s beneficiaries. Bygones are bygones, and not a useful guide to tomorrow’s policy choice.

A third point of interest is that there are a lot of ‘moving parts’ in the Government’s proposals for increased taxes on defined benefit schemes.

As far as can be determined form the Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials, the tax offset for untaxed defined benefit schemes would be capped at a pension of $100,000 p.a.; the value of any pension of $100,000 or more would be deemed to have a value of ($100,000 * 16), so any pension with capped tax offset would be valued at a transfer balance of $1.6 million, thereby exhausting the balance cap of the retiree.

Any additional savings such a retiree might have made in any other super fund are immediately declared excess to the retiree’s personal transfer balance cap. So any additional super savings are immediately forced out of the retirement phase and their earnings taxed at 15% in an accumulation fund.

Finally, any pension over $100,000 p.a would have half of the excess over $100,000 added to the pensioner’s annual income and taxed at the beneficiary’s top marginal rate.This is potentially a triple jeopardy for defined benefit super pensioners, and it is not immediately clear if the three increases combined are more or less commensurate with the increased taxes on other high-transfer balance self-funded retirees.

The Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials notes that important issues for significant numbers of defined benefit retirees are still not resolved.[xlix] It invites comments on how these unresolved issues that have defeated policy advisers for four months may be addressed — something not possible within the short time allowed for public consultation.

14. Lower minimum drawdown amounts on super pensions

The tranche two measures take effect when global growth prospects are poor, advanced economy growth is still falling, and many interest rates are near-zero or negative in real terms.[l]

Those nearing retirement and self-funded retirees are commonly advised to stick to low-risk portfolios of fixed interest and similar products, and re-weight portfolios away from potential growth assets with high volatility such as domestic and foreign equities. But now they grapple with an era of ‘return-free risk’ and still have to withdraw a minimum amount of from 4 to 14% a year (rising with age) under the legal requirements that have to be met for retirement annuities to enjoy a tax exemption for the investment earnings of the super fund assets (below their personal transfer balance cap) supporting them. [li] In a ‘return-free risk’ environment, these drawdown requirements amount to a rule for accelerating real decline in retirement phase super balances. Put differently, they add to encouragements to stop saving and go for the part aged pension.

The Budget tax increases will further reduce living standards of those affected, adding to the squeeze between falling market returns and minimum drawdown amounts still rising with age.

The Government should act immediately on the recommendation of the Retirement Income Streams Review to seek Australian Government Actuary recommendations for lower minimum drawdown amounts on super pensions, as were applied from 2008-09 to 2012-13.[lii] Those recommendations should address realistic, bleak prospects for future earnings, not the past multi-decadal history of equity booms and dot-com bubbles.

15. Innovative income streams: more costs of ‘effective retrospectivity’

Chapter 8 of the Exposure Draft Explanatory Materials in part outlines an intent to extend the earnings tax exemption that the Budget removes from those current retirement income streams arising from a transfer balance cap above $1.6 million. The extended concession would apply to innovative lifetime products such as ‘deferred products’ and ‘group self-annuities’ that may emerge in the future. Such products, were savers ever to demand them, would permit a belated start to pension payments, thereby possibly addressing savers’ need to manage longevity risk.[liii]

For example, a super saver aged 55 in 2017 could purchase a ‘deferred pension’ that commences at age 80. Legislation in 2017 would provide an earnings tax exemption on the funds supporting that pension from the date the saver satisfies a condition of release, such as attaining the age of 65 in 2027 (para 8.35). Then the retiree would gain tax-free income from the deferred annuity in 2042. The assets supporting the annuity would by then be larger than otherwise by the compounding of 15 years’ earnings growth since 2027 with no tax on the earnings.

In a world where the Government is withdrawing with ‘effective retrospectivity’ the earnings tax exemption on assets already lawfully saved over a lifetime, and destroying a tax-free annuity under existing law to those already retired, why would anyone buy a deferred annuity that would not start payment until a quarter-century in the future? That would merely provide the next 8 governments with 25 years in which to withdraw the new tax concession with ‘effective retrospectivity’.

When a future government withdraws without grandfathering the ‘deferred pension’ concession of 2017, they could cite the precedent of the Turnbull/Morrison Budget of May 2016; they could say that the super concessions were too expensive, too unfair and unsustainable; argue that 95% or 99% of people would not be adversely affected; and that the only losers were already very old, wouldn’t need much money at that stage of life, and could access the age pension if they needed to.

This problem underlines a dilemma created by the Budget measures. The Government can only offer facilitating a decrease in longevity risk at the same time as it has increased the regulatory risk of future ‘effectively retrospective’ law changes. The net effect is zero, or worse.

The example illustrates the unbounded damage caused by increasing super tax without grandfathering. Any government’s ability to induce or facilitate a desired objective depends on citizens trusting that it will play fair, abide by its own laws, and change them only with prospective effect. When a government destroys trust, it destroys all plausible influence on future developments that depend on keeping its word.

By destroying confidence in super through ‘effectively retrospective’ changes, the proposed measures re-weight Australians’ retirement planning towards smaller super balances and higher reliance on a part age pension.

The time allowed for public consultation on the Government’s complex measures is derisorily short. History has shown that rushed and ill-considered super changes lead to spiraling complexity and the need for additional changes to correct unintended consequences.

The Government should take its second tranche measures back to the drawing board, along with the first tranche of new super tax expenditures, and the unworkable statement of objectives for superannuation.

The Government should bring forward a quantified and transparent statement of the net effect of its preferred measures on the retirement living standards of Australians and on retirement policy costs (both superannuation and age pension) to the budget. The evaluation should use a sensible recasting of the presently unworkable Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016, and should demonstrably meet the requirements of the recast Bill.

The Government should review the misleading but ubiquitous estimate of the high cost of superannuation concessions, and switch to a conceptually defensible measure such as illustrated by Treasury’s 2013 ‘experimental estimate’ of super concession costs. It should address the suggestions in the reports by the Henry tax review and the Cooper Charter Group that when appropriately measured in net terms (ie allowing for the reduction in age pension costs, if only from reduced access to the full pension ) the costs of superannuation concessions may be very small or even negative.

The Government should contest the view that use of superannuation concessions is unfair, because allegedly regressive. In fact, use of super concessions is roughly proportionate to super savers’ contribution by decile to overall income tax collections.

The Government should contest the view that ‘fairness’ is a one-dimensional construct requiring redistribution from anyone richer to anyone poorer, to be achieved by conscripting every aspect of every policy until reaching the only logical end point, complete equality. It should emphasise that ‘fairness’ includes ideals of fair reward for effort and fair reward for thrift, leading to self-sufficiency, and reducing dependence on the state and the taxes of one’s fellow citizens. Fairness also involves keeping one’s commitments. To be fair, governments should keep their commitments. Redistributive fairness is certainly also important, but should be judged by the overall progressiveness of the tax and transfer system, which is already very high in Australia.

If the proposed legislation is passed by the House of Representatives, the Senate should subject it to careful scrutiny. It should refer the whole of the Government’s proposed superannuation package to a Senate Committee. The Senate Committee should invite and consider public submissions and objections.

The package should include appropriate grandfathering provisions. That would maintain the sound practice of at least the last 40 years of changes in Australian super law, and maintain trust in superannuation.

[i] The term ‘effective retrospectivity’ was coined by Scott Morrison, Address to the SMSF 2016 National Conference, Adelaide, 18 February 2016. See quote on title page. The term captures the essence of the problem caused by the Budget measures for retirees and those near retirement, and is used consistently in the remainder of this submission.

[ii] Scott Morrison, Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and sustainable superannuation) bill 2016: exposure draft explanatory materials, Canberra October 2016. See especially paras 1.172and 1.227.

[iii] Peter Costello, A Plan to Simplify and Streamline Superannuation: Detailed Outline, Canberra, May 2006

[iv] Peter Costello, Simplified Superannuation – Final Decisions, Press Release 093 , 5 September 2006

[v] Scott Morrison and Kelly O’Dwyer, Superannuation reforms: first tranche of Exposure Drafts , 7 September 2016

[vi] Scott Morrison, Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016, Explanatory Materials, p6, para 1.16

[vii] Peter Costello, A Plan to Simplify and Streamline Superannuation: Detailed Outline, Canberra, May 2006, p 1

[viii] John Roskam, The Turnbull Government Backs An Unprincipled Purpose Of Super, 9 September 2016,

[ix] Terrence O’Brien, Submission on First Tranche of Superannuation Exposure Drafts, 16 September 2016

[x] Tony Negline, Saving or slaving: find the sweet spot for super, The Australian, 4 October 2016.

[xi] Terrence O’Brien, Grandfathering super tax increases, Centre for Independent Studies, Policy, Vol. 32 No. 3 (Spring, 2016), pp3-12

[xii] Terrence O’Brien, Examination of proposed super changes, letter of 7 September 2016 to Government members.

[xiii] Terrence O’Brien, ibid.

[xiv] Robert Menzies, The Forgotten People, 22 May 1942

[xv] Kelly O’Dwyer, Dispelling myths perpetuated by base politicking, The Australian, 10 May 2016.

[xvi] Swoboda, K., Major superannuation and retirement income changes in Australia: a chronology, Parliamentary Library Research paper Series 2013-14, Attachment 2, 11 March 2014

[xvii]Peter Costello, Tax Laws Amendment (Simplified Superannuation) Bill 2006, Explanatory Memorandum, C2006B00226.

[xviii] Peter Costello, footnote 7 above, section 1.2

[xix] Scot Morrison and Mathias Cormann, Budget Measures, Budget Paper No 2, 2016-17, 3 May 2016, p 25

[xx] Australian Taxation Office[xxi] Robert Cincotta of Anderson Partners, Chartered Accountants, estimates that the extra annual compliance cost for Self Managed Superannuation Funds affected by the proposed new superannuation law will be approximately $3,000 to $4,000, depending on the circumstances of each Self Managed Superannuation Fund.

[xxii] Tracy Oliver and Scott Bartley, Tax system complexity and compliance costs — some theoretical considerations, Treasury Economic Roundup, winter 2005.

[xxiii] Scott Morrison, Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016, Explanatory Materials, p6, para 1.16.

[xxiv] Scott Morrison and Kelly O’Dwyer, Even Fairer, More Flexible and Sustainable Superannuation, Media Statement, 15 September 2016.

[xxv] Ken Henry et al, Australia’s future tax system, Report to the Treasurer, Part Two, Detailed analysis, Volume 1, December 2009, p 12.

[xxvi] Simon Cowan, The Myths of the Generational Bargain, Centre for Independent Studies, Research Report 10, 1 March 2016.

[xxvii] Scott Morrison, Address to the SMSF 2016 National Conference, Adelaide, 18 February 2016.

Many of you know that there are different ways to measure the size of these concessions; I know ASPRA (sic) in particular take some exception to the way tax expenditures statements are used or, I should say, abused by some in this debate. Tax expenditure statements do not represent costings. They do not truly reflect what the cost to revenue actually is and the way they are combined also inappropriately by some advocates, particularly the Opposition, misrepresents the cost to the Government in what amounts to expenditures that are provided in tax concessions. I think this is an area that we can continue to refine and get right and ASPRA has some excellent suggestions about how we might achieve to do that, as does the SMSF Association. We hope to achieve that together with all of the organisations in the sector. They don’t, these tax expenditures statements, represent the potential revenue gain to the Government as many have claimed.

Some say these concessions are as high as $30 billion. Others believe it could be as low as $11 billion. The task is to weigh up the value of superannuation tax concessions against other uses for how that revenue might be applied.

In fact, these two numbers are not just ‘beliefs’; they are both Treasury estimates. The first uses a comprehensive income tax as a hypothetical benchmark, and the second uses one of several valid expenditure tax benchmarks. Both numbers are gross, not allowing for savings from reduced access to the age pension induced by the concessions.

[xxviii] Robert Carling, Right or Rort? Dissecting Australia’s Tax Concessions, Centre for Independent Studies, Research Report 2, April 2015.

[xxix]Mark Day, Tax cuts: A lesson for Duncan Storrar and Q&A, The Australian, 16 May 2016.

[xxx] Scott Morrison, Address to the SMSF 2016 National Conference, Adelaide, 18 February 2016.

[xxxi] Robert Carling, How should super be taxed?, Centre for Independent Studies, Policy, Vol. 32 No. 3 (Spring, 2016), p 20,

[xxxii] A classic example is the Green’s superannuation policy that concessional (i.e. pre-tax) contributions to super, presently taxed at a flat 15%, should instead be taxed at progressive rates of up to 32%. Moreover, there should also be a welfare payment: anyone earning below the tax–free threshold of $18,200 and locking away savings in super for 40 years (hello – anyone there?) should receive a payment from other taxpayers of 15c for every dollar they save.

On the progressiveness of Australia’s tax/benefit system, see Dick Warburton and Peter Hendy, International comparison of Australia’s taxes, April 2006, Section 4.5.

[xxxiii] Terrence O’Brien, Grandfathering super tax increases, Centre for Independent Studies, Policy, Vol. 32 No. 3 (Spring, 2016), pp4-6.

[xxxiv] Scott Morrison, Address to the SMSF 2016 National Conference, Adelaide, 18 February 2016.

[xxxv] Ross Gittins, A light on the hill for our future tax reformers, The Age 15 June 2009.

[xxxvi] Jeremy Cooper, A Super Charter: Fewer Changes, Better Outcomes: A report to the Treasurer and Minister Assisting for Financial Services and Superannuation, Canberra, 5 July 2013.

[xxxvii] Jeremy Cooper, ibid, p 16.

[xxxviii] Terrence O’Brien, Grandfathering super tax increases, Centre for Independent Studies, Policy, Vol. 32 No. 3 (Spring, 2016), pp3-12.

[xxxix] Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Political Legitimacy, revised 13 May 2016.

[xl] Terrence O’Brien, Examination of proposed super changes, letter of 7 September 2016 to Government members.

[xli] Jeremy Cooper, Before super tax changes, remember the pension is worth $1 million, Australian Financial Review, 19 April 2015.

[xlii] Trish Power, Crunching the numbers: a $1.6 million retirement, SuperGuide, 23 May 2016.

[xliii] Tony Negline, Saving or slaving: find the sweet spot for super, The Australian, 4 October 2016.

[xliv] Scott Morrison, Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and sustainable superannuation) bill 2016: exposure draft explanatory materials, Canberra October 2016, p 14 para 1.31

[xlv] Scott Morrison, ibid, p 19.

[xlvi] Scott Morrison, ibid, p 67, para 1.259.

[xlvii] Scott Morrison, ibid, p 18.

[xlviii] Anne Willenborg, Annette Barbetti and Trevor Nock , How the CSS and PSS work, SCOA SuperTime Newsletter, May 2014.

[xlix] Scott Morrison, op cit, para 1.172 p46.

[l] International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook: Subdued Demand: Symptoms and Remedies, October 2016.

[li] Trish Power, Minimum pension payments for 2015/16 and 2017/17 years, SuperGuide, 17 May 2016.

[lii] The Treasury, Retirement Income Streams Review, Canberra, 3 May 2016.

[liii] Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016, Explanatory Materials, ibid, pp 102-109, especially para 8.35

6 pings

[…] Save Our Super has considered the second tranche of the Government’s superannuation changes. On 10 October 2016, Terrence O’Brien and Jack Hammond QC, on behalf of themselves and Save Our Super lodged with Treasury their joint submission in response to the second tranche. That joint submission is available here. […]

[…] On 10 October 2016, Terrence O’Brien and Jack Hammond QC, on behalf of themselves and Save Our Super lodged with Treasury their joint submission in response to the second tranche. That joint submission is available here. […]

[…] Submission on Tranche Two: 10 October 2016 […]

[…] Click here for the submission (see section 15). […]

[…] Our Super has argued in its submissions to Treasury on exposure drafts of the superannuation Bills and to the government and the Senate Committee on the Bills that the […]

[…] See Section 5 of Save Our Super, Submission on Second Tranche of Superannuation Exposure Drafts, 10 October […]