26 August 2020

Senator The Hon Jane Hume

The Assistant Minister for Superannuation, Financial Services and Financial Technology

The Treasury

Langton Cres

Parkes ACT 2600

CC: Robert Jeremenko, Retirement Income Policy Division, The Treasury

By email: senator.hume@aph.gov.au/Robert.Jeremenko@treasury.gov.au

Dear Assistant Minister

Proportional Indexation of the Personal Transfer Balance Cap

The Tax Institute requests the Government to consider the reforms outlined below in relation to Division 294 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997) – that is, the transfer balance cap (TBC) provisions.

Division 294 was included as a part of the 2016-17 Federal Budget Superannuation Reforms and introduced a cap on the amount of superannuation benefits an individual could transfer into pension (tax-free retirement) phase. The General TBC was initially set at $1.6 million1 upon commencement from 1 July 2017. The law includes the indexation, in increments of $100,0002, of the TBC in line with movements in the CPI.

Section 294-40 of the ITAA 1997 provides for individuals that have not reached their TBC to access proportional indexation of the TBC in accordance with their unused cap percentage.

The Tax Institute considers that this provision is overly complex and needs to be reformed. In the context of the TBC provisions, The Tax Institute submits that simpler rules would:

- Assist members and their advisers to better understand and manage the TBC; and

- Reduce the cost for both industry participants and the ATO in relation to administering these provisions.

The Institute submits that the removal of proportional indexation will achieve both of these objectives. Accordingly, the Institute’s submission is as follows:

- Abolish proportional indexation of the Personal TBC and adopt standardised indexation in line with movements in the General TBC for individuals that have not maximised their Personal TBC prior to the indexation; or

- If proportional indexation is retained:

- it should be limited, or its application better targeted to individuals that are within close proximity of the General TBC; and

- a permanent relief mechanism should be introduced to allow the Commissioner to disregard inadvertent and small breaches of the Personal TBC and not penalise individuals in cases where the excess transfer balance amount is removed within a specified period of time. There is a precedent that was included in the enabling legislation whereby TBC breaches of less than $100,000 were able to be rectified within 6 months (of the commencement of the legislation) and the breaches would not give rise to the application of notional earnings or an excess transfer balance tax liability3. We suggest adopting this transitional rule permanently (with some modification if required).

The requested reforms have been developed by The Tax Institute’s National Superannuation Technical Committee and are detailed in Annexure A for your consideration.

* * * * *

If you would like to discuss, please contact either me or Tax Counsel, Angie Ananda, on 02 8223 0050.

Yours faithfully,

Peter Godber

President

ANNEXURE A

Overview

Part of the 2016-17 Federal Budget superannuation reforms introduced (from 1 July 2017) a lifetime cap on the amount of accumulated superannuation an individual could transfer into pension (tax-free retirement) phase. The General Transfer Balance Cap (TBC) was initially set at $1.6 million4.

Apart from some specific circumstances prescribed in the law, amounts in excess of the TBC must be withdrawn out of pension phase. The excess amounts could remain either in the accumulation phase with associated earnings taxed at 15 per cent or completely transferred out of the superannuation system. Notably, the General TBC would be indexed and allowed to grow in line with the CPI, in increments of $100,0005.

In addition, a Personal TBC was introduced within the enabling legislation6 which is generally equal to the General TBC applicable at the time when an individual makes their first transfer of capital to a retirement phase income stream.

The ATO administers individual compliance with the TBC via a Transfer Balance Account (TBA).

Proportional indexation

Section 294-40 of the ITAA 1997 provides for proportional indexation of the TBC to allow individuals to benefit from increases in the General TBC where they have not fully expired their entitlement to their Personal TBC.

The structure of proportional indexation, over time, results in individuals having a Personal TBC that differs from the General TBC relative to the time they commence a retirement phase income stream.

Complexity is further added as an individual can only obtain a proportion of each General TBC indexation increase (that is, $100,000), based on their Unused Cap Percentage (UCP).

The UCP applies only if the individual has not fully utilised their Personal TBC and is determined by identifying the individual’s highest TBA balance at the end of a day, at an earlier point in time, and comparing it to their Personal TBC on that day. The UPC is expressed as a percentage and applied against the indexation available for the General TBC. This process is required at each indexation point until such time as the individual utilises 100% of their Cap Space.

Once an individual has used their entire available Cap Space, their Personal TBC is not subject to further indexation, even if they later commute some or all of that pension to bring their TBA balance below their Personal TBC.

This is best illustrated with the following examples (adapted from the Explanatory Memorandum)7:

Example – simple

Danika first commenced an $800,000 retirement phase income stream on 18 November 2017. A Transfer Balance Account is created for her at this time. Her Personal TBC was $1.6m for 2017-18. As Danika had not made any other transfers to her retirement phase account, her highest TBA balance is $800,000. She has used 50% of her $1.6m Personal TBC.

Assuming the General TBC is indexed to $1.7m in 2020-21, Danika’s Personal TBC is increased proportionally to $1.65m. That is, Danika’s Personal TBC is only increased by the UCP of 50% of the $100,000 indexation increase to the General TBC. As such, Danika can now transfer a further $850,000 to commence a retirement phase income stream without breaching her Personal TBC. Notably, earnings on the original $800,000 were not taken into account in working out how much of the unused cap was available.

Example – complex

On 1 October 2017, Nina commenced a retirement phase income stream with a value of $1.2m. On 1 January 2018, Nina partially commuted $400,000 from this income stream to buy an investment property.

Nina’s TBA balance on 1 October 2017 was $1.2m and on 1 January 2018, it was $800,000 (after the $400,000 partial commutation).

In 2020-21, assume the General TBC is indexed to $1.7m. To work out the amount by which Nina’s Personal TBC is indexed, it is necessary to identify the day on which her TBA balance was at its highest. In this case, the highest balance was $1.2m on 1 October 2017. Nina’s Personal TBC on that date was $1.6m. Therefore, as she has used up 75% of her Personal TBC, Nina’s UCP on 1 October 2017 is 25%.

To work out how much her Personal TBC is to be indexed, Nina’s UCP is applied to the amount by which the General TBC has indexed (i.e. $100,000). Therefore, Nina’s Personal TBC in 2020-21 is $1.625m.

In 2022-23, assume the General TBC is indexed to $1.8m (i.e. by another $100,000). As Nina has not transferred any further amount into the retirement phase, her UCP remains at 25%. Her Personal TBC is now

$1.65m (i.e. 25% of the further indexation increase of $100,000). In this year, Nina decides to transfer the maximum amount she can into the retirement phase.

This will be her Personal TBC for the 2022-23 year ($1.65m) less her TBA balance of $800,000. This means Nina can transfer another $850,000 into the retirement phase without exceeding her Personal TBC.

Once Nina has used all of her available Cap Space, her Personal TBC will not be subject to further indexation. Notably, this is the case even if Nina later partially commutes some of her retirement phase income stream and makes her TBA balance fall below her Personal TBC.

Range of Potential Personal TBC

Members (A to D) Cap Space utilised in 2018 – 2021 (assuming indexation in 2021).

| Personal TBC (Start) | Year | Cap Space Accessed | Total Used | Unused Cap %8 | Personal TBC (End) | Year | |

| A | $1,600,000 | 2018 | $1,600,000 | $1,600,000 | Nil | $1,600,000 | 2018 |

| B | $1,600,000 | 2018 | $1,000,000 | $1,000,000 | 38% | $1,638,000 | 2021 |

| C | $1,600,000 | 2018 | $ 700,000 | $ 700,000 | 57% | $1,657,000 | 2021 |

| D | $1,700,000 | 2021 | $1,000,000 | $1,000,000 | N/A | $1,700,000 | 2021 |

Members (A to D) Cap Space utilised in 2022 – 2025 (assuming further indexation in 2025).

| Personal TBC (Start) | Year | Cap Space Accessed | Total Used | Unused Cap % | Personal TBC (End) | Personal TBC Year | |

| A | $1,600,000 | 2022 | Nil | Nil | Nil | $1,600,000 | 2025 |

| B | $1,638,000 | 2022 | $ 500,000 | $1,500,000 | 9% | $1,647,000 | 2025 |

| C | $1,657,000 | 2022 | $ 900,000 | $1,600,000 | 4% | $1,661,000 | 2025 |

| D | $1,700,000 | 2025 | Nil | $1,000,000 | 42% | $1,742,000 | 2025 |

As illustrated above, the amount of proportional indexation largely depends on an individual’s UCP, each time there is indexation of the General TBC.

The result of this process is an individual’s Personal TBC is likely to be unique to themselves if they are in the category where they do not utilise their full TBC at the point of commencing a retirement phase income stream.

The burden is therefore likely to fall to individuals with smaller superannuation balances.

Current Issues and Challenges

Overly complex calculation and too widely targeted

The above examples demonstrate the complexity of the proportional indexation calculation which, over time, will require very effective record management systems to track and be effective in ensuring individuals are not subject to inadvertent breaches of their TBC.

According to the Explanatory Memorandum9 (EM) to the enabling legislation, the introduction of the TBC was to better target superannuation concessions thereby ensuring the system’s sustainability over time. The EM estimated the introduction of the TBC would affect less than one per cent of Australians with a superannuation interest. If this estimate is accurate, then arguably this particular calculation which is carried out on the full population (in retirement phase) represents a very inefficient and costly tax administration for what was meant to only have a one per cent application.

Design not hitting target

By its very nature, proportional indexation essentially rewards and benefits those who are able to defer the commencement of their retirement phase income stream to a later date. As a consequence, it may actually encourage those who are ready to retire (with amounts in excess of the General TBC) to defer and leave their superannuation balance in the accumulation phase until indexation does occur. Such behaviour would appear contrary to the intent and objective of proportional indexation.

Inconsistent treatment with other superannuation caps

The proportional indexation of the Personal TBC is unprecedented when compared with other indexation that takes place under the tax law. For instance, the Low Rate Cap Amount10 which represents a lifetime cap on the tax-free level of superannuation lump sums an individual can receive in their lifetime is indexed in line with AWOTE, in increments of $5,000. There is no proportional reduction based on how much of the previous Low Rate Cap Amount has remained unused.

Too many rates, caps and thresholds

It has taken industry participants and the ATO considerable time and effort to educate individuals on the concept of the TBA (including debits and credits) and the consequences of breaching their Personal TBC. At times, there has even been some confusion with the Total Superannuation Balance (TSB) which has also been pegged to the General TBC for the purposes of assessing eligibility to the following superannuation concessions:

- Non-concessional contributions caps (NCC) and associated bring forward caps;

- Government co-contributions;

- Tax offset for spouse contributions; and

- Segregated method to determine their earnings tax exemption (SMSFs and small APRA funds only).

We submit that there was a logical nexus and a familiarity developed with the $1.6 million between the General TBC and the TSB (at least for the above mentioned superannuation concessions). However, as proportional indexation comes into effect with an individual potentially having a Personal TBC not equalling the General TBC, The Tax Institute is concerned that the Personal TBC will further exacerbate what is becoming a very complex suite of rates, caps and thresholds operating within the superannuation system.

A lack of consistency has been applied historically across the various caps and eligibility criterion for superannuation concessions. Some caps are indexed based on either CPI or AWOTE whereas others are referenced to a specific date and/or data set.

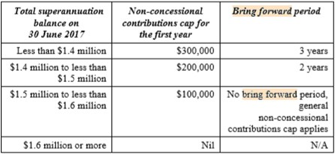

The non-concessional bring forward non-concessional contributions cap (that allows some individuals to use 3 years of the non-concessional contribution cap in a single year), provides an example of the anomalies apparent in the reference points for access to superannuation concessions.

The bring-forward non-concessional contributions cap is assessed based on an individual’s TSB, with thresholds referencing both the General TBC and the General NCC.

Source: Paragraph 5.47 of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 – Explanatory Memorandum.

Specifically, the references to $1.4 million, $1.5 million and $1.6 million reflect a calculation that takes a multiple of the NCC (originally set at $100,000) and subtracts it from the General TBC11.

Notably the table above gets very complicated and may produce anomalous eligibility thresholds given the indexation of the General TBC is based on CPI and the General NCC on AWOTE. This problem is further exacerbated if, in a given income year, the NCC is indexed but the General TBC is not (due to the higher $100,000 incremental hurdle).

Access difficulties to Personal TBC

Currently, financial planners and advisers have difficulties accessing clients’ TBA and TSB balances given the information is only accessible via the ATO and restricted to the individual and their tax agents.

Without this information, it is extremely difficult for advisers to provide appropriate financial advice which will not cause their clients to inadvertently breach their caps. Unfortunately, we foresee this problem only getting worse if and when proportional indexation comes into effect with an individual’s Personal TBC diverging from the General TBC12. This ultimately affects the quality of the advice provided and may lead to errors, giving rise to complaints and the need to remediate.

Reliance on ATO

Of particular concern is that the Personal TBC determination rests solely with the ATO, who in turn must rely on all Fund providers to report all relevant member’s transactions accurately and in a timely fashion. Any errors or omissions in the reporting may lead to subsequent re-reporting which may trigger a re-calculation of the Personal TBC. However, the individual and/or their financial adviser may have acted and relied upon the ATO’s calculation.

Notably in a recent AAT case13, a taxpayer submitted that they were led into error by misleading content on the ATO website when managing the excess over their Personal TBC. However, the Tribunal found in favour of the ATO and also confirmed that the Tribunal had no jurisdiction to address any application against the ATO even if its website could be said to be misleading This was the case, notwithstanding there was acknowledgement that the taxpayer had relied on the ATO information in good faith and made an honest mistake.

Furthermore, there appears to be no rights to object to any inadvertent breach of the individual’s Personal TBC in such a situation and is a real concern given the fact that the Commissioner does not explicitly have any discretionary powers to disregard an excess transfer balance (even if information obtained from the ATO contributed to the breach).

Culpability for errors or omissions unclear

As alluded to in the previous issue, it may also be unclear as to who is culpable for an inadvertent breach of the cap as a consequence of any error or omission in member reporting. With such a large superannuation system and the volume of transactions that occur, one can expect reporting errors

or omissions to arise from time to time that require re-reporting to the ATO. To the extent re-reporting causes a subsequent breach of the cap and/or denial of any related superannuation concessions, it is unclear who is culpable for that breach. This is particularly the case if the individual has multiple accounts with various Fund providers and there are errors or omissions experienced by more than one Fund provider.

Severe tax consequences for excess transfer balances not rectified

The breaching of the TBC may often lead to an individual disputing their excess transfer balance with the ATO and refusing to commute the excess. Individuals may give explicit instructions to their Fund not to process a commutation authority issued by the ATO. However, Trustees have no choice but to act and process a commutation authority that it receives14. Failure to do so within the prescribed 60 days will result in the income stream ceasing to be a retirement phase income stream15.

This in turn results in the income stream ceasing to qualify for the earnings tax exemption16 with the eligibility deemed to have been lost from the start of the income year in which the commutation authority was not complied with. Notably this tax outcome poses an administrative challenge particularly for large funds that operate retail Master Trusts and offer their members superannuation interests in unitised asset pools. Specifically, it becomes extremely difficult to even determine what portion of the income and gains from the unitised (pension) asset pools is attributable to that particular member. Furthermore, the Trustee would also need to assess the tax character of that income and gains, plus any applicable tax offsets in order to determine the effective earnings tax rate that ought to have been applied to the deemed assessable income.

More importantly, the Trustee’s compliance with a commutation authority may give rise to a complaint by the member for not complying with their explicit instruction or request not to process.

Outcomes and Conclusion

The current superannuation system is overly complex and costly to administer. There is merit in making it much simpler for all stakeholders.

The Tax Institute submits that simpler rules would assist in:

- Members and their advisers better understanding and managing the TBC; and

- Reducing the cost for both industry participants and the ATO to administer these rules.

The removal of proportional indexation specifically achieves both these objectives.

As with other existing superannuation caps, adopting the General TBC will ensure every individual has the same TBC regardless of when they entered the retirement phase. This will provide certainty to individuals and their advisers to better plan for their retirement, without having to rely on gaining access to ATO information.

The call for permanent relief for inadvertent and small breaches is aimed at red tape reduction and thereby increasing the overall efficiency of the superannuation system. At present, it can take up to 120 days before an excess transfer balance amount is withdrawn from retirement phase. Any such breaches tend to involve every party within the system and is therefore a very costly and time- consuming exercise. We submit this particular option strikes a good balance between maintaining the integrity and efficiency of the superannuation system. It should also obviate any breaches which may result from any misreporting and re-reporting of member transactions by Fund providers and reduce the number of disputes and complaints raised by the individual against the Trustee and/or the ATO.

Whilst the proportional indexation methodology is designed to target higher member balances, its universal application is more likely to impact superannuation funds with lower balance members. The Tax Institute considers it to be undesirable to significantly increase the complexity inherent in a system that has limited application against the object of the measure. There is still time to remove this provision from Division 294 before the first indexation event occurs and we urge the Government to carefully consider this submission.

____________________________________________________________________________________

1 Subsections 294-35(3) of the ITAA 1997.

2 Subsection 960-285(7) of the ITAA 1997.

3 Section 294-30 of the IT(TP) Act 1997

4 Subsections 294-35(3) of the ITAA 1997.

5 Subsection 960-285(7) of the ITAA 1997.

6 Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Act 2016 [No. 81 of 2016].

7 Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 – Explanatory Memorandum.

8 Unused cap percentage effectively is rounded up to the nearest per cent as a result of subsection 294-40(2)(c) of the ITAA 1997.

9 Paragraph 3.373 of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Fair and Sustainable Superannuation) Bill 2016 – Explanatory Memorandum.

10 Section 307-345 of the ITAA 1997.

11 Subsections 292-85(2), (3), (4) and (5) of the ITAA 1997.

12 Indexation of the General TBC will first occur (in the following income year) if and when the December quarter CPI figure reaches 116.9.

13 Lacey and Commissioner of Taxation (Taxation) [2019] AATA 4246.

14 Section 136-80 in Schedule 1 to the TAA 1953.

15 Subsection 307-80(4) of the ITAA 1997.

16 Subdivision 295-F of the ITAA 1997.

Click here for The Tax Institute’s original submission published 28 Aug 2020 by THE TAX INSTITUTE

************************************************************