15 October 2018

Jim Bonham

“Having a non-means tested government payment solely on the criteria that you own shares and giving people a refund when you haven’t actually paid income tax for the year that the refund covers, what’s the economic theory behind that?” asked Opposition Leader Bill Shorten recently, and reported by Phillip Coorey in the Australian Financial Review on 12 October 2018.

Mr Shorten is talking about refundable franking credits, but actually franking credits are means tested (because they’re taxable income and our progressive tax scales are a form of means testing), and you have paid income tax (because franking credits are also pre-paid tax) and, finally, there is an economic theory (to ensure gross dividends are taxed as ordinary income).

Unfortunately, that’s not the way the ALP sees it.

Shadow Treasurer Chris Bowen, said refundable franking credits are “a concession”, “unfair revenue leakage” and “a generous tax loophole” when describing the ALP’s plan to stop the refunding of unused franking credits (see SuperGuide article https://www.superguide.com.au/smsfs/shorten-retirement-tax-refunds-franking-credits and and the ALP’s policy document, https://www.chrisbowen.net/issues/labors-dividend-imputation-policy/ )

Those comments are not right either. Refundable franking credits are part of an unfortunately convoluted and widely misunderstood process, but their function is straightforward: to ensure that Australian company profits distributed to Australian shareholders are taxed in the hands of the owners (shareholders) rather than the company, in exactly the same way as income from any other source. The company is only taxed on that part of its profit which is kept in the company for internal use, and not distributed.

In our present system of refundable franking credits therefore, there is no concession, no leakage and no loophole.

In the discussion referenced above, the Shadow Treasurer also said “While those people [with low taxable incomes] will no longer receive a tax refund, they will not be paying additional tax” which is a prime piece of Orwellian double-speak. It’s not correct, and shareholders on sufficiently low incomes will find that their franking credits are simply confiscated as tax – money they get now will no longer be received and they will have less to live on.

Australians on low incomes will lose franking credits, unless they receive a part or full Age Pension. After strong protests that convinced the ALP that its policy would actually harm those on low incomes, they announced the “Pensioner Guarantee” – an exemption from the policy for Age Pensioners who hold shares directly, and for SMSFs where at least one member received the Age Pension or a government allowance before 28 March 2018 – but that still doesn’t help non-pensioner shareholders with low incomes.

In this article, I dig into this subject in more detail, particularly for those who hold their shares directly in their own names, to show what the ALP proposal really means and how it would operate.

I’ll show that the policy can cause very substantial loss of income for direct shareholders, especially those on low or middle incomes. Retirees will simply not be able to suck up the sort of losses involved and we can expect some creative asset reduction to get under the Age Pension asset test threshold, or a major restructure of the investment portfolio to avoid franked dividends.

Dividend imputation, and how franking credits work

In the bad old days when dividends paid from company profits (taxable in Australia) were double-taxed, it worked like this: the company paid tax at the corporate rate (currently 30%) on the relevant profit; the remainder (70% at current rates) was sent as a dividend to the shareholders, who then paid further tax on it as part of their ordinary income.

In 1987, the Hawke-Keating government decided to remove this double taxation of dividends, introducing a dividend imputation system similar to what we have today, except that franking credits were non-refundable.

Although the company still paid tax at the corporate rate (currently 30%), any of that tax which was associated with profits paid out as a dividend was reclassified as a “franking credit” and held by the ATO as a pre-payment of tax on behalf of the taxpayer – very similar to the PAYE system

The franking credit was also treated as part of the shareholder’s taxable income. In other words, the gross dividend, which is the franking credit plus the dividend, was added to any other taxable income when calculating the shareholder’s income tax. The franking credits, being pre-paid tax, were then subtracted from the calculated tax owing, so that in the end the gross dividend was taxed just like any other income.

For high-income shareholders, whose tax liability exceeded the value of the franking credits, this system had the effect of transferring the liability for tax on company profits from the company to the shareholder.

However, for low-income shareholders the situation was different. If there were franking credits left over after paying the tax, the ATO simply kept the excess. (This outcome is what is meant by “non-refundable”). Taxpayers who would have paid no tax at all if the same amount had been earned from employment, actually paid the corporate tax rate on their dividends. Their dividend income was “taxed in their own hands”, but not taxed like other income.

In 2000, the Howard-Costello government made unused franking credits refundable to the taxpayer, creating the current system in which gross dividends are always taxed as shareholder’s income, regardless of the shareholder’s tax rate.

Here’s a simple example to show how the three systems treat low and high income taxpayers. For this example, “low income” means too low to pay tax in our current system and “high income” means over $180,000 so the marginal tax rate is 47% (including the Medicare levy). It’s also assumed that the gross dividend is not large enough to alter the taxpayer’s marginal tax rate, and today’s tax rates are used.

The table shows how much money, after tax, ends up in the shareholder’s pocket as a result of $100 profit earned by the company and distributed as a dividend. Clearly, low-income recipients of franked dividends will be the hardest hit if the ALP re-introduces non-refundable franking credits.

| System | After tax income from $100 profit | |

| Low income | High income | |

| Double taxation (prior to 1987) | $70 | $37 |

| Non-refundable franking credits (Hawke-Keating) | $70 | $53 |

| Refundable franking credits (Howard-Costello) | $100 | $53 |

Dividend imputation with non-refundable franking credits was a have-your-cake-and-eat-it-too system for the government, where that part of a company’s profits distributed as dividends was taxed at either the corporate or the personal tax rate, whichever gave the higher result. This is the system the ALP wants us to return to – Age Pensioners (mostly) excepted.

So who is most affected by the proposed policy? What is their income? How much income will they lose? How effective is the Pensioner Guarantee? Let’s look at these questions in some detail.

Significant loss of income under ALP proposal for direct shareholders

People who hold shares directly, outside of superannuation, may be rich or struggling; they may be retired or in their youth; they may rely on dividends from shares for all of their income, or just a part of it; they may have other taxable income from dividends, rental, employment etc. They might also receive non-taxable income from a superannuation pension, but that has to be looked at separately and does not affect what happens with their taxable income.

Whatever the circumstance, the introduction of the ALP’s policy will result in either a loss of income or, if the shareholder’s income is high enough, no change. No one gains except the government.

If a shareholder is going to lose income under the ALP policy, the actual amount depends on total taxable income, the amount of gross dividends as a percentage of the total, and whether the taxpayer is entitled to SAPTO (and if so, whether single or a member of a couple).

Incidentally, wherever I use the phrase “entitled to SAPTO”, it is to be understood that the entitlement only applies if the income is below the appropriate threshold. Above that, the “entitled to SAPTO” and “not entitled to SAPTO” curves in the graphs to follow are, of course, identical.

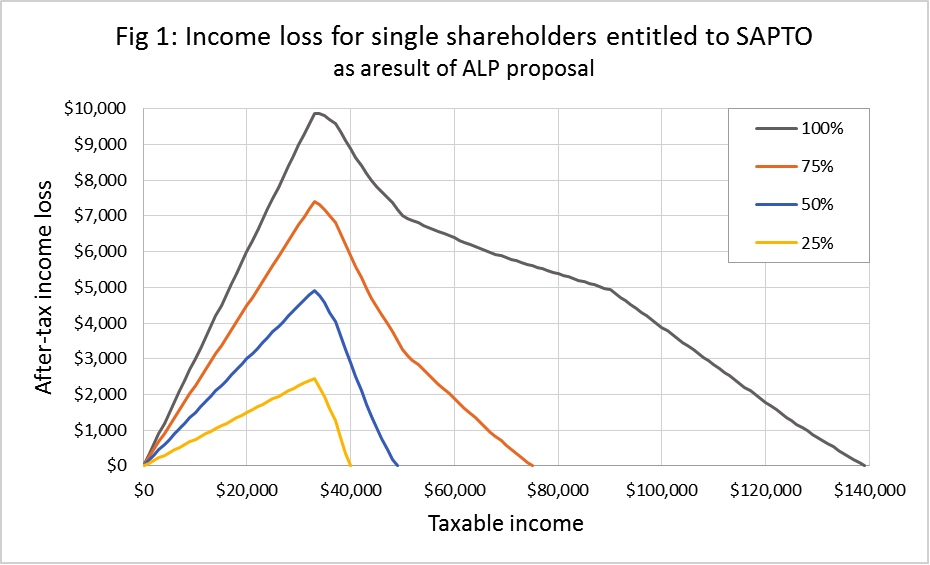

Fig 1 presents the loss of income which would result from the ALP proposal for a single senior shareholder entitled to SAPTO, where the gross dividends received constitute 25%, 50%, 75% or 100% of the shareholder’s total taxable income.

For example, if gross dividends represent 100% of a taxpayer’s income, the introduction of the ALP proposal will be most financially devastating for single senior Australians earning about $33,000 a year but will also affect those earning up to about $138,000 a year. If gross dividends represent 75% of a taxpayer’s income, the ALP proposal will most severely hurt single senior Australians earning about $33,000 a year but will also affect those earning up to about $75,000 a year

In all scenarios, single senior Australians with low to moderate incomes will be most affected by the ALP’s proposal to ban franking credits refunds.

Figure 2 shows the same results, but for a senior taxpayer who is a member of a couple. Note this graph is just one partner’s share of both the income and the loss. The shapes of the curves are a bit different from those in Fig 1 because of the complicated structure of our tax scales.

Note: In particular, for a couple, if gross dividends make up 50% or less of total income, the worst loss occurs at an income (each) of about $22,000.

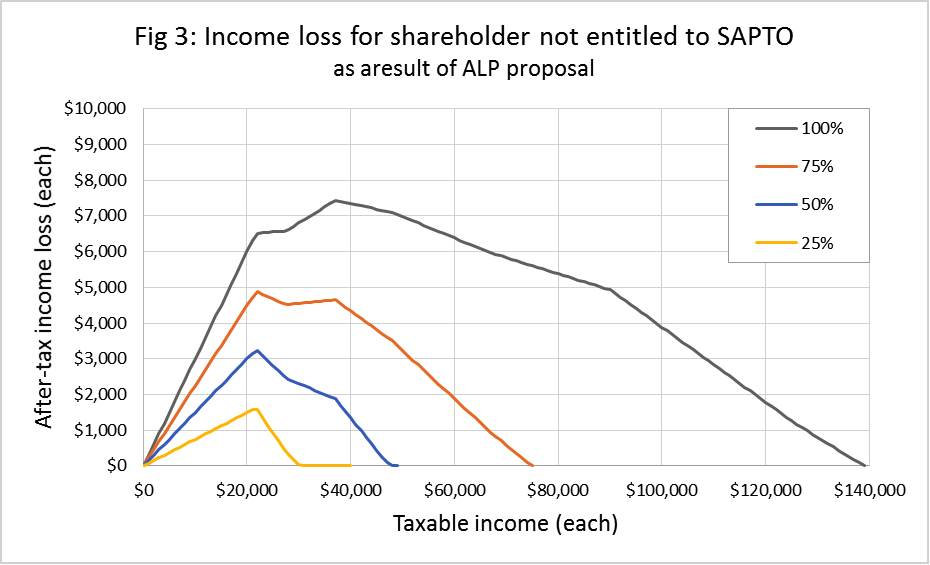

Finally, Fig 3 shows the same results for a younger taxpayer who is not entitled to SAPTO.

In each of these three graphs the curves are skewed towards lower incomes and the greatest amount of income loss occurs at a taxable income of between $22,000 and $33,000 depending on the individual case. That’s hardly a huge income, yet in the worst case the ALP proposal will reduce this income by up to $10,000 per year, depending on the percentage of franked shares contributing to taxable income. The proportional loss is savage.

For those who don’t qualify for SAPTO, the maximum loss of income occurs at lower taxable incomes and is not quite as large, but it is still very significant in relation to the level of income

This is just another slap in the face to seniors who, in recent years, have suffered the doubling of the Age Pension asset test taper rate, dramatic upheaval in the structure of superannuation in retirement and now, for share investors, the threat of losing some or all of their franking credits.

Many retirees must question why they put so much effort in their younger years into saving and learning how to invest, only to have their assets and income so badly trashed by continually changing rules.

What about the Age Pension?

When introducing this policy, the ALP claimed that it would mostly affect wealthy retirees. A strong backlash led to the Pensioner Guarantee (exemption) and the claim that they were thus protecting those less well off.

However, that did nothing for those who fail to qualify for the Age Pension but still don’t have much income. We need to see where in Figs 1 or 2 the Age Pension might cut out.

To keep things as simple as possible, we’ll just look at the top curves in Figs 1 and 2, which assume that gross dividends make up all the taxable income. In both cases, the worst loss occurs for a taxable income of about $33,000, and if we assume a gross dividend yield of 6% (approximately the average for fully franked shares in the ASX 200) the value of the shares needed to generate that income is $550,000.

The upper asset test threshold for the Age Pension is different for singles and couples, and for those who own their own homes:

| Asset test upper threshold | ||

| Homeowner | Not homeowner | |

| Single | $564,000 | $771,000 |

| Couple (each) | $424,000 | $511,000 |

None of these figures are very far from $550,000. What that means is that someone who just fails to qualify for the Age Pension, and so is not excluded from the ALP policy, will probably find themselves facing close to the maximum loss of income.

How will people respond?

With incomes at these levels, nobody’s going to just suck up the sort of losses involved, so expect either (a) some creative asset reduction to get under the Age Pension asset test threshold, or (b) a major restructure of the investment portfolio to avoid franked dividends.

The first alternative, that is, creative asset reduction, is likely to trap the person into permanent dependence on the Age Pension, restricting a person’s ability to improve her financial position in future or to deal with major health or care issues late in life. The second alternative, restructuring the investment portfolio, could adversely affect the risk of the portfolio producing poor returns, leading to an inadvertent slide onto the Age Pension.

Either way the objective of the ALP proposal is thwarted, which makes it rather pointless to make people jump through these hoops, while putting more people on the Age Pension

SMSFs also hit by ALP proposal

The ALP’s proposal also applies to shares held within a self-managed super fund.

If an SMSF is in accumulation mode, then the tax rate on investment earnings and discounted capital gains is 15%. In such circumstances, if gross dividends make up more than half the total income, some of the franking credits will be lost. I suspect most people caught in this situation will restructure their investments to bring gross dividends down below 50% of income. Such a strategy solves the tax problem, but may adversely alter the SMSF’s risk profile.

SMSFs in pension mode are in a much more difficult situation. They pay zero tax on fund earnings, but under the ALP proposal they would lose all of their franking credits, which could be up to 30% of their current income. Portfolio restructure is one option to avoid this tax (although it would mean abandoning shares paying franked dividends), as is simply reducing (spending) assets so as to bring their value low enough to qualify for the Age Pension – in both cases with the possible consequences outlined earlier.

Unfortunately, reducing the value of shares held in the SMSF – as a deliberate strategy or simply to supplement income – to the point where a retiree qualifies for a part Age Pension still won’t protect the franking credits. The Pensioner Guarantee does not apply to SMSF members who qualify after 28 March 2018, so retirees in this situation will probably consider closing their SMSF and reinvesting outside super.

SMSFs in pension mode seem to be the main target of the ALP’s proposal, and the Shadow Treasurer’s statement (https://www.chrisbowen.net/issues/labors-dividend-imputation-policy/ ) specifically refers to the fact that some SMSFs get very large refunds of franking credits. Well yes, some did, but that was largely eliminated by capping superannuation pension accounts at $1.6 million. Meanwhile, lots of people have relatively small SMSF pension accounts.

If the real problem that the ALP is trying to address is the fact that SMSFs in pension mode pay no tax, then that should be addressed directly with full consideration of context including large funds as well as SMSFs. It is a fundamental and complex issue and simply changing the way dividends are taxed is not the way to deal with it.

Destructive and unfair tax policy

Halting the refund of excess franking credits is a very destructive policy for those who hold shares directly or in an SMSF, especially in pension phase

Such a proposal puts a severe strain on retirees whose taxable income is fairly low unless they can find a way to restructure their investments or qualify for the Age Pension, but it has little or no effect on wealthier people – unless their investment is through an SMSF in pension mode.

Likely responses to the policy would see some people driven to the Age Pension, at long-term cost to themselves and the government. Others will close their SMSF purely to get under the umbrella of the Pensioner Guarantee. Some may decide to remove all Australian shares paying franked dividends from their portfolios – how is this good for themselves or the country?

Income tax is often arbitrary and complex, but the basic principle of dividend imputation with refundable franking credits is simple and sound: to ensure profits distributed as dividends are taxed as normal income in the hands of shareholders. Why mess that up?

The ALP policy is the antithesis of a well-designed tax policy, a direct slap in the face to the notion of a progressive tax system, and an extraordinary proposition to have come from the ALP.

Exempting Age Pensioners who hold shares directly from this policy was painted as supporting those on low incomes, but really it was just a way of papering over part of a problem and hoping no-one would notice the rest.

Technical note: All tax calculations in this article use 2018-19 tax rates, and include LITO, LMITO, SAPTO (if relevant) and the Medicare levy. The Age Pension asset test thresholds are applicable from September 2018. For more information on income tax rates see SuperGuide article https://www.superguide.com.au/boost-your-superannuation/income-tax-rates. For more information on Age Pension assets test, see SuperGuide article https://www.superguide.com.au/accessing-superannuation/age-pension-asset-test-thresholds .

About the author: Jim Bonham

Dr Jim Bonham is a retired scientist and R&D manager, who is deeply concerned about the appalling instability of the regulatory environment around superannuation, retirement funding and investment generally. If the ALP policy is implemented, he will be affected by the loss of franking credits in relation to shares held directly, and within an SMSF.

Copyright: Jim Bonham owns the copyright to this article. Copyright © Jim Bonham 2018

First published on 15 October 2018 on SuperGuide: https://www.superguide.com.au/retirement-planning/alps-franking-credits-policy-targets-shareholders-low-taxable-incomes

On 16 October 2018 Jim Bonham sent the following email to Bill Shorten and Chris Bowen:

From: Jim Bonham [mailto:jim@bonham.id.au]

Sent: Tuesday, 16 October 2018 9:19 AM

To: ‘Bill.Shorten.MP@aph.gov.au‘ <Bill.Shorten.MP@aph.gov.au>

Cc: ‘Chris.Bowen.MP@aph.gov.au‘ <Chris.Bowen.MP@aph.gov.au>

Subject: Franking credits

Dear Mr Shorten,

I was dismayed to read the following quote, attributed to you, regarding refundable franking credits:

“Having a non-means tested government payment solely on the criteria that you own shares and giving people a refund when you haven’t actually paid income tax for the year that the refund covers, what’s the economic theory behind that?” (https://www.afr.com/news/bill-shorten-promises-biggest-preelection-policy-agenda-since-gough-whitlam-20181011-h16ju0 )

The facts are:

- Refunds of franking credits to shareholders with low taxable income are means tested, because franking credits are taxable income and the progressive nature of income tax system effectively applies a means test.

- You have paid income tax, because the franking credit is treated by the ATO as a pre-payment of tax. The refund to those on low taxable incomes occurs because the pre-payment is an over-payment.

- There is an economic theory. The dividend imputation process was designed to ensure that company profits distributed as dividends are taxed in the hands of the shareholder (the company is only taxed on profits retained for internal use). Refunding franking credits in excess of the shareholder’s tax obligation is essential to ensure that the gross dividend is taxed in the same way as other income. Failing to refund excess franking credits, as the ALP is proposing, forces those on low taxable incomes to pay a higher rate of tax on gross dividends than they would if the same income were earned in any other way.

Please abandon the policy of making franking credits non-refundable. It hits those with low taxable incomes the hardest, and makes living in retirement on your own resources far more difficult for self-funded retirees.

Jim Bonham

1 ping

[…] https://saveoursuper.org.au/alps-franking-credits-policy-targets-shareholders-with-low-taxable-income… […]