Australian Financial Review

June 12, 2018

David Knox

How does Australia fare globally when it comes to retirement incomes?

Our superannuation savings framework is often highlighted as a long-term success of the decisions made in the 1980s and 1990s. Yet the latest OECD numbers show that the system is not delivering an acceptable level of retirement income across all wage earners.

When compared with 10 other countries with similar economies, Australia’s results are skewed.

Odd as it may seem, Australia’s wealthiest and the very poorest are doing well from our compulsory superannuation system. But average wage earners are not. This incongruity means that the system is far from perfect.

So is there a better way, a way that will also result in better outcomes, for even those who expect a very comfortable retirement? Is a universal pension the answer?

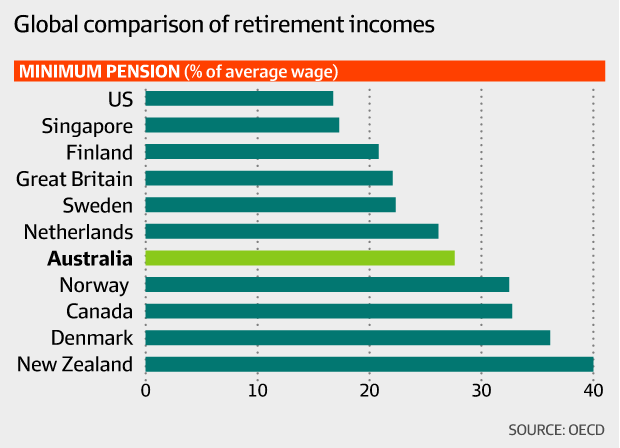

First let’s look at the income provided to the poor, when expressed as a percentage of the average wage. The first graphic shows the Australian age pension provides an income that is slightly above the average when compared to the 10 similar countries. So far, so good.

Now let’s consider an individual who receives the average income throughout their career.

Retirement income

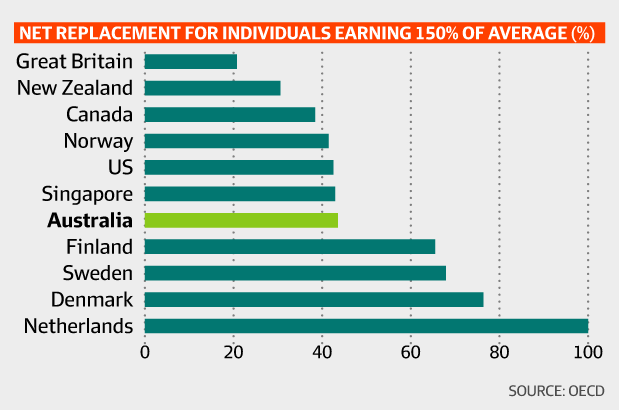

The second graphic shows the net replacement rate, assuming they join the workforce at 20 and retire at the future pension age of 67. The net replacement rate, as calculated by the OECD, is the after-tax income received during the retirement years divided by the after-tax income received before retirement.

These net replacement rates range from 29 per cent for the UK to above 100 per cent for the Netherlands with an average of 56 per cent.

Australia is the second-lowest of the 11 countries with a net replacement rate of just over 40 per cent. An important factor driving this relatively poor result is the stronger assets test for the age pension that was introduced from January 1, 2017.

In most countries, the net replacement rate decreases as incomes rise. The reasoning is simple: those with higher incomes do not need the same replacement rate as those on lower incomes. Perversely this does not happen under our current system of the means-tested age pension and compulsory superannuation.

The last chart shows the comparison for an individual who earns 150 per cent of the average wage throughout their career.

Although the net replacement rate in many countries falls as incomes rise, the Australian results are the opposite – with the rate increasing from 40.7 per cent for the average income earner to 43.4 per cent for the 150 per cent earner and then to 44.9 per cent for an individual who earns twice the average wage.

The causes of this outcome are twofold.

First, the superannuation tax system is flat for most income earners, unlike the income tax system which is progressive. This is in contrast to most countries in this comparison where benefits are taxed in a progressive manner. Second, our assets and income tests on the age pension mean that average income earners are expected to receive very little age pension during their retirement years.

Fairer system

The Australian retirement income system has many positive features including coverage of most employees, but the outcomes for the average income worker in respect of retirement incomes needs to be improved.

This would not only improve adequacy but would provide a fairer system. The question is: how can this be done in a simple and sustainable manner?

One way is to follow the Danish system where part of the pension is paid to everyone as taxable income, with the balance paid on an income-tested basis. For example, the current age pension could be divided into two components: a pension equal to 10 per cent of the average wage paid to everyone and an income-tested pension equal to the balance, namely 17.6 per cent of the average wage.

An immediate response could be that Australia, which has an ageing population, can’t afford this.

However, the current and projected Australian government expenditure on the age pension is the lowest of the 10 OECD countries in this comparison. This situation raises the potential to enable pension expenditure to be increased slightly, when expressed as a percentage of GDP, without imposing a significant burden on the federal budget.

The introduction of a universal part-pension has several advantages including the provision of the health card – which would remove the incentive for many retirees to deliberately rearrange their affairs to receive a part-pension and therefore the health card. Such an outcome would encourage all retirees to maximise their assets and income.

A universal pension would improve the retirement income for the average income earner but would have a reduced effect at higher incomes as it would represent a fixed payment in dollar terms. In other words, it would remove the effect that above-average income earners receive a higher net replacement rate.

Clearer incentive

As the income-tested pension would represent less than 18 per cent of the average wage, the income test would cease to have any effect where other income exceeded about 40 per cent of the average wage.

This would provide a much clearer incentive for those with the capacity to save to do so, whereas such behaviour is not always rewarded under the current system. This includes those who may receive a higher income at various stages during their career.

As with all the other countries in this comparison, a single income test should be applied, including deemed income on all assets. This would remove the need for a dual means test which complicates the system. Full-rate pensioners would not be affected.

There would, of course, be an extra expense to the government budget. However, this would be offset, at least to some extent, by additional income tax from those with higher taxable incomes and – possibly – a reduced demand on government services due to the extra income and the changed behaviour as additional saving would be clearly rewarded.

The universal pension could also be seen as an unnecessary gift to the wealthy. However this extra cost could be offset by some adjustments in the total system affecting high income earners, thereby producing a more efficient retirement system without an adverse impact on equity within the overall system.

Dr David Knox is a senior partner at Mercer. These ideas were discussed at the recent Actuaries Institute Financial Services Forum.